Andry Rajoelina

| Andry Rajoelina | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the High Transitional Authority of Madagascar | |

|

In office 17 March 2009 – 25 January 2014 | |

| Prime Minister |

Monja Roindefo Eugène Mangalaza Cécile Manorohanta (Acting) Albert Camille Vital Omer Beriziky |

| Preceded by | Marc Ravalomanana |

| Succeeded by | Hery Rajaonarimampianina |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

30 May 1974 Antananarivo, Madagascar |

| Political party | Young Malagasies Determined |

| Spouse(s) | Mialy Razakandisa |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism[1] |

Andry Rajoelina (Malagasy: [ˈjanɖʐʲ nʲˈrinə radzoˈel]) (born 30 May 1974) was the President of the High Transitional Authority of Madagascar. He became president on 21 March 2009 during a political crisis, having held the office of Mayor of Antananarivo for one year prior, and stepped down on 25 January 2014 following internationally recognized general elections held in 2013. Before entering the political arena, Rajoelina launched several successful enterprises, including a printing and advertising company called Injet in 1999 and the Viva radio and television networks in 2007. He began his career as an entrepreneur in his teenage years, first as a disc jockey at local clubs and parties, and later by organizing and promoting musical events in the capital.

Upon rising to power, Rajoelina dissolved the Senate and National Assembly and transferred their powers to a variety of new governance structures he made responsible for overseeing the transition toward a new constitutional authority. These administrative structures repeatedly conflicted with the internationally mediated process to establish a transitional government of consensus. Voters approved a new constitution in a national referendum unilaterally organized by the Rajoelina administration in November 2010, ushering in the Fourth Republic and putting in place the conditions enabling Rajoelina to stand in the next general election. In January 2013 he announced his decision to abstain from running in the 2013 general election, but in May 2013 he reversed this decision and submitted his candidature. A special electoral court ruled in August 2013 that his candidature was invalid and that Rajoelina would not be permitted to run in the 2013 election. He has declared an interest in presenting himself as a presidential candidate in a future election.

Early years

Andry Rajoelina was born on 30 May 1974 to a relatively wealthy family in Antananarivo. His father, now-retired Colonel Roger Yves Rajoelina, held dual nationality and fought for the French army in the Algerian War.[2][3] At the age of 13, Rajoelina became the 1987 junior-class national karate champion.[4] While still in high school, Rajoelina began working as a disc jockey at parties and clubs in Antananarivo to earn pocket money.[5] Although Rajoelina's family could afford a college education for their son, he opted to discontinue his studies after completing his baccalaureat to launch a career as an entrepreneur.[3]

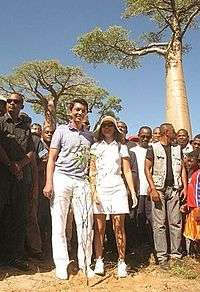

In 1994, Rajoelina met his future spouse Mialy Razakandisa, who was then completing her senior year at a high school in Antananarivo. The couple courted long-distance for six years while Mialy completed her undergraduate and masters studies in finance and accounting in Paris; they were reunited in Madagascar in 2000 and wed the same year. Their marriage produced two boys, Arena (born 2002) and Ilonstoa (born 2005), and a daughter born in 2007 that the couple named Andrialy, a contraction of their own names.[6]

Media entrepreneur

In 1993, at the age of 19, Rajoelina established his first enterprise: a small event production company called Show Business. The connections and influence of his father, then a prominent military officer, in combination with Rajoelina's own knowledge of Antananarivo nightlife, were factors in the company's success. By the following year, he had firmly established his reputation among the youth elite of the capital for organizing an annual concert called Live that brought together foreign and Malagasy musical artists. The event continued to grow in popularity with each passing year, attracting 50,000 participants on its tenth anniversary.[5]

In 1999, he launched Injet, an advertising and digital printing company that quickly grew in prominence with its expansion of billboard advertising throughout the capital.[5] The business was the first to make digital printing technology available on the island. Local magazine Echo Australe,[4] which named then-mayor of Antananarivo Marc Ravalomanana their Entrepreneur of the Year in 1999, bestowed the same honor on Rajoelina in 2000.[3] Following Rajoelina's marriage in 2000, his wife's wealthy parents invested in Injet and allowed Rajoelina in 2001 to acquire Domapub, a competing Antananarivo-based billboard advertising business that they owned.[7] The couple worked together to manage the family businesses, with Rajoelina responsible for Injet and his wife handling the affairs of Domapub.[6] A competition organized by French bank BNI Crédit Lyonnais awarded first prize for best young entrepreneur in Madagascar to Rajoelina in 2003.[8]

Rajoelina's business affairs gradually drew him into the political arena. Shortly after Ravalomanana won the presidential elections in 2001, Rajoelina befriended the new president's daughter and continued to expand his relationship with the capital's political elite over the course of the Ravalomanana presidency.[3] He assumed an increasingly political role after the policies of Ravalomanana's Tiako I Madagasikara (TIM)-dominated government increasingly obstructed the expansion of his business activities,[7] such as requiring the removal of Antananarivo's first LED advertising panels, which Rajoelina had installed at a major roundabout in the capital.[9] In May 2007 he purchased the Ravinala television and radio stations, which he renamed Viva TV and Viva FM. The official launch of these newly acquired media channels on 27 May was attended by many of the capital's political and cultural elite, including Antananarivo mayor Hery Rafalimanana and Jacques Sylla, president of the TIM political party.[5] Rajoelina used these media channels as outlets for voicing criticism of the Ravalomanana administration, quickly transforming his public image into that of an opposition leader.[7]

Mayor of Antananarivo

In 2007 Rajoelina created and led the political association Tanora malaGasy Vonona (TGV), meaning "determined Malagasy youth". Shortly afterward he announced his candidacy for the position of Mayor of Antananarivo.[7] Rajoelina was elected on 12 December 2007 with 63.3% of the vote and a 75% voter turnout,[10] beating TIM party incumbent Hery Rafalimanana.[5] Although Rafalimanana enjoyed strong popularity during his tenure as mayor, having been nationally and internationally credited with effectively managing the capital and achieving significant transformation of the urban landscape in the city, his campaign suffered from inadequate TIM promotional support and the increasingly unpopular image of the TIM party.[11]

Rajoelina faced significant challenges in his tenure as mayor. Upon taking office, he was confronted with redressing the city's treasury, which had accumulated 8.2 billion Malagasy Ariary (approximately 4.6 million U.S. dollars) in debts under previous mayors, including Ravalomanana himself.[12] Beginning 4 January 2008, Ravalomanana ordered water cutoffs at public pumps and brownouts of Antananarivo's street lights run by the state utilities company Jirama, due to 3.3 million ariary of unpaid debts to Jirama by the City of Antananarivo. Rajoelina responded by condemning the move as political and proceeded to undertake an audit that identified and addressed long-standing procedural irregularities and issues of corruption within the city's administration.[13] Following a series of crimes against members of Rajoelina's inner circle in 2008 that comprised the burgling of his cabinet director's car, the kidnapping and ransoming of one of his special advisers, and the death of an assistant under mysterious circumstances, rumors spread that the Rajoelina administration was being deliberately intimidated by supporters of the president.[14]

Confrontation with Ravalomanana

On 13 December 2008, the Government closed Andry Rajoelina's Viva TV, stating that a Viva interview with exiled former head of state Didier Ratsiraka was "likely to disturb peace and security".[15] This move catalyzed the political opposition and a public already dissatisfied with other recent actions undertaken by Ravalomanana,[16] including the July 2008 deal with Daewoo Logistics to lease half the island's arable land for South Korean cultivation of corn and palm oil,[17] and the November 2008 purchase of a second presidential jet at a cost of 60 million U.S. dollars.[16] Within a week Rajoelina met with twenty of Madagascar's most prominent opposition leaders, referred to in the press as the "Club of 20", to develop a joint statement demanding that the Ravalomanana administration improve its adherence to democratic principles. The demand was broadcast at a public press conference where Rajoelina also promised to dedicate a politically open public space in the capital which he would call Place de la democratie ("Democracy Place").[18]

Beginning in January 2009, Andry Rajoelina led a series of political rallies in downtown Antananarivo where he gave voice to the frustration that Ravalomanana's policies had triggered, particularly among the economically marginalized and members of the political opposition. On 17 January he gathered 30,000 supporters at a public park and declared it renamed Place de la democratie.[15] At a rally on 31 January 2009 Rajoelina announced that he was in charge of the entire Malagasy Republic, declaring: "Since the president and the government have not assumed their responsibilities, I therefore proclaim that I will run all national affairs as of today." He added that a request for President Ravalomanana to formally resign would shortly be filed with the Parliament of Madagascar.[19] This self-declaration of power discredited Rajoelina in the eyes of many of the supporters who had rallied around his original pro-democracy message, and the number of attendees at subsequent rallies declined, averaging around 3,000 to 5,000 participants.[15]

On 3 February, Ravalomanana dismissed Rajoelina as mayor of Antananarivo and appointed a special delegation headed by Guy Randrianarisoa to manage the affairs of the capital. Rajoelina denounced the decision and warned that it would not be accepted by the populace.[20] The following day Rajoelina instead designated Michele Ratsivalaka to succeed him as mayor. Rajoelina incited demonstrators on 7 February to occupy the presidential palace, prompting the presidential guard to open fire on the advancing crowd, killing 31 and wounding more than 200.[16] Popular disapproval of Ravalomanana intensified and polarized some in favor of his resignation, although perceptions of Rajoelina as an alternative remained mixed.[15] Conflicts between pro-Rajoelina demonstrators and security forces continued over the following weeks, resulting in several additional deaths. The security forces unsuccessfully attempted to arrest Rajoelina at his compound on 5 March; they also raided the offices of his Viva media network. Initially they surrounded Viva, and after thirty minutes the staff attempted to remove Viva property, at which point the security forces stormed the building and confiscated the equipment.[21] For the next several days Rajoelina took refuge in the home of the French ambassador, reporting to the press that he feared for his safety.[22]

On 11 March, following a declaration of neutrality by army leadership, pro-opposition soldiers from the CAPSAT (Army Corps of Personnel and Administrative and Technical Services) stormed the army headquarters and forced the army chief of staff to resign.[23] Over the next several days the army deployed forces to enable the opposition to occupy key ministries,[24] the chief of military police transferred his loyalty to Rajoelina,[25] and the army sent tanks against the president's Iavoloha Palace.[26] Rajoelina rejected Ravalomanana's offer on 15 March to hold a national referendum to determine whether the president should resign, and called on security forces to arrest the president.[27] The following day, the army stormed the president's Ambohitsorohitra Palace and captured the Central Bank.[28] Hours later Ravalomanana transferred his power to group of senior army personnel, an act described by the opposition as a voluntary resignation, although Ravalomanana later declared he had been forced at gunpoint to relinquish power.[29] The military council would have been charged with organizing elections within 24 months and re-writing the constitution for the "Fourth Republic".[30] However, Vice Admiral Hyppolite Ramaroson announced on 18 March that it would transfer power directly to Rajoelina, making him president of the opposition-dominated High Transitional Authority (HAT) that he had appointed weeks earlier. With the military's backing, the authority was charged with taking up the task previously accorded to Ravalomanana's proposed military directorate.[31] Madagascar's constitutional court deemed the transfer of power, from Ravalomanana to the military board and then to Rajoelina, to be legal;[32] the court's statement did not include a justification for its decision.[33]

Upon the army's transfer of power to Rajoelina, Malagasy navy troops called for his resignation by 25 March, threatening to use force otherwise to protect the constitution of Madagascar and denouncing Rajoelina for the "civil war occurring in Madagascar". The navy troops claimed there was "irrefutable" evidence that Rajoelina had paid the army corps hundreds of millions of ariary and that they should face trial in accordance with military law, but called for other nations not to get involved in what they considered a purely domestic affair.[34] Rajoelina was sworn in as President on 21 March at Mahamasina stadium before a crowd of 40,000 supporters.[35] He was 35 years of age when sworn in, making him the youngest president in the country's history and the youngest head of government in the world at that time.[36]

The Southern African Development Community, a bloc of 15 nations including Madagascar, announced on 19 March that it would not recognize Rajoelina's presidency since the takeover was unconstitutional.[37] His ascension to the presidency was also condemned by the European Union and the United States,[38] and the African Union suspended Madagascar and threatened sanctions if the constitutional government had not been restored in six months.[39] No foreign diplomats attended Rajoelina's investiture;[33] the HAT foreign minister said none had been invited.[40]

President of the High Transitional Authority

Rajoelina took power in an atmosphere of national tension and international pressure to re-establish constitutional authority. The new head of state announced on 17 March that a new constitution would be presented for voter approval and general elections would be held within 24 months.[41] Immediately after taking office, Rajoelina began naming opposition leaders to positions within the HAT. He dissolved the Senate and Parliament and transferred their powers to his cabinet, the officials of the HAT, and the newly established Council for social and economic strengthening, through which his policies were issued as decrees. Legislative authority rested in practice with Rajoelina and his cabinet, composed of his closest advisers. A military committee established in April increased HAT control over security and defense policy. The following month, after the suspension of the country's 22 regional governors, Rajoelina strengthened his influence over local government by naming replacements despite the fact that regional governorships were normally elected positions. The National Inquiry Commission (CNME) was established shortly thereafter; although its official purpose was to strengthen HAT effectiveness in addressing judicial and legal matters, the new entity carried out investigations and arrests of TIM supporters and other opponents of the TGV party. In addition, the new administration launched a strong crackdown on demonstrations by the new opposition, composed largely of Ravalomanana supporters; at two demonstrations in April 2009 security forces opened fire on unarmed civilians protesting the HAT's closure of three media networks formerly controlled by Ravalomanana, killing four and wounding sixty.[16] Political analysts have criticized Rajoelina for using his position primarily to consolidate power and protect his political position and business interests and those of his supporters, observing that his initially broad range of supporters within the opposition movement has significantly diminished over time.[15]

While in power, Rajoelina periodically engaged in ongoing negotiations to establish conditions under which free and fair elections could be held to restore government constitutionality and legitimacy in the eyes of the international community. On 4 August 2009 Rajoelina met with former Madagascar presidents Ravalomanana, Ratsiraka and Zafy along with former Mozambican President Joaquim Chissano acting as mediator at the four-day mediation crisis talks held in Maputo, Mozambique.[42] The Maputo Accords signed by the four leaders in August and further accords signed in Addis-Abeba in November provided guidelines for a period of consensual political transition. In the months that followed, however, Rajoelina obstructed the implementation of the accords, making unilateral political decisions and filling all important government posts with TGV party representatives.[16]

After being pushed back repeatedly,[43] a constitutional referendum was held on 17 November 2010 that resulted in adoption of the state's fourth constitution with 73% in favor and a voter turnout of 52.6%.[44] The independent Malagasy political watchdog group KMF-CNOE,[45] as well as the political opposition and the international community, cited numerous irregularities in the process, which was carried out unilaterally by the HAT.[46] The constitution in effect at the time Rajoelina took office required that presidential candidates attain a minimum of 40 years of age.[47] One substantive change made by the new constitution was to lower the minimum age for presidential candidates from 40 to 35, making Rajoelina eligible to stand in presidential elections.[48] In addition, the new constitution mandated the leader of the High Transitional Authority – the position held by Rajoelina – be kept as interim president until an election could take place.[49][50] The new constitution also contained a clause that required presidential candidates to have lived in Madagascar for at least six months prior to the elections, effectively barring Ravalomanana and other opposition leaders living in exile from running in the next election.[50] After being repeatedly postponed, the general election was held on 25 October 2013.[51]

Policies and governance

The HAT under Rajoelina's leadership affected highly visible, concrete activities that appealed to popular concerns. Rajoelina occasionally organized events to distribute basic items to groups of poor recipients, including medicines, clothing, house maintenance materials and school supplies.[52] Rajoelina's administration also spent billions of ariary to subsidize basic needs like electricity, petrol,[53] and food staples.[54] Public works construction projects featured prominently among Rajoelina's activities. In 2010, two years after Rajoelina launched the project as mayor of Antananarivo, the HAT completed the reconstruction of the Hotel de Ville (town hall) of Antananarivo which had been destroyed by arson during the rotaka political protests of 1972.[55] Also in 2010, Rajoelina oversaw the construction of a hospital built to international standards in Toamasina.[56] Through its trano mora ("cheap house") initiative, the HAT built several subsidized housing developments intended for young middle class couples.[57] Numerous other construction projects were planned or completed, including the restoration of historic staircases in Antananarivo built in the 19th century during the reign of Queen Ranavalona I,[58] renovation of Toamasina's two main markets and its principal boulevard, repaving of the heavily traveled road between Toamasina and Foulpointe, and the construction of a 15,000-capacity municipal stadium and new town hall in Toamasina.[56]

On the national level, sanctions and suspension of donor aid amounting to 50 percent of the national budget and 70 percent of public investments obstructed the Rajoelina administration's management of state affairs and its ability to systematically combat poverty on a wider scale.[59] A United Nations envoy concluded in 2011 that Rajoelina's controversial accession to the presidency had reduced food security, with Madagascar ranking among the worst in the world for child nutrition.[60] The frequent non-payment of civil servant and military salaries resulted in regular school and hospital closures, general strikes and widespread increases in corruption. Crime and insecurity grew dramatically, with a sharp upswing in violent crime and theft in Antananarivo and increasingly frequent and deadly incidences of armed cattle rustling in the central southern region of the island. Key development indicators steeply declined between 2009 and 2013, including maternal and child mortality, education enrollment and completion, per capita income and employment rates.[61][62] In 2010 the United Nations ranked Madagascar among the ten poorest countries in the world, noting that economic gains made under Ravalomanana had been lost following Rajoelina's unconstitutional rise to power.[63] In 2011, Forbes magazine ranked Madagascar as the worst economy in the world, faulting its political instability and poor governance.[64]

Environmental conditions on the island also worsened under Rajoelina. The illegal exportation of endangered rosewood from protected national forests abruptly increased under the HAT, with several business leaders and politicians linked to the HAT having been implicated in trafficking the valuable wood to China; NGOs and the US government accused the Rajoelina administration of selling the wood to supplement the national budget and finance its public works projects.[61][65] A large, unexplained stash of rosewood logs was discovered at the presidential palace after the end of Rajoelina's term in office.[66] Due to accelerating deforestation and a spike in bush meat consumption linked with deepening poverty, the island's lemurs moved closer toward extinction under Rajoelina's tenure.[67] A July 2012 assessment found that 90 percent of lemur species were found to be threatened with extinction, an increase from 38 percent in 2008.[68] Lack of funds for pesticides and systematic spraying resulted in the March 2013 outbreak of a locust infestation that was anticipated to persist for five to ten years[69] and require $41 million U.S. dollars to bring under control, deepening the risk of nationwide famine[70] and destruction of habitat for endangered species.[71]

After coming to power, Rajoelina's HAT pursued action against Ravalomanana and his business interests. On 2 June 2009, Ravalomanana was fined 70 million US dollars (42 million British pounds) and sentenced to four years in prison for alleged abuse of office which, according to HAT Justice Minister Christine Razanamahasoa, included the December 2008 purchase of a second presidential jet ("Air Force II") worth $60 million.[72] Rajoelina sold the controversial jet in 2012[73] and pursued legal action against Ravalomanana's company Tiko to reclaim 35 million US dollars in back taxes.[74] Additionally, on 28 August 2010, the HAT sentenced Ravalomanana in absentia to hard labor for life and issued an arrest warrant for his role in the protests and ensuing deaths.[75] Rajoelina likewise sought to distinguish himself from his predecessor in policy choices. One of Rajoelina's first measures as president was to cancel Ravalomanana's unpopular deal with Daewoo Logistics.[76] He also rejected Ravalomanana's medium term development strategy, termed the Madagascar Action Plan, and abandoned education reforms initiated by his predecessor that adopted Malagasy and English as languages of instruction, instead returning to the traditional use of French.[61]

Diplomatic relations

The international community maintained that Rajoelina's legitimacy was conditional to free and fair elections.[77] A number of key international organizations in which Madagascar had been a member, including the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union, withheld recognition of Rajoelina's legitimacy throughout his tenure. The United States, Madagascar's largest bilateral donor and provider of humanitarian aid, also refused to acknowledge the Rajoelina administration.[37][38][39] The United Nations responded to the power transfer by freezing 600 million euros in planned aid. The United States suspended Madagascar from the list of beneficiaries of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which had ensured preferential tariffs for the import of Malagasy textiles. This sanction resulted in the loss of over 50,000 jobs and dealt a severe blow to the textile sector, which had accounted for half of Madagascar's exports.[60] Rajoelina initially sought to persuade former donors to recommence their support; when these efforts failed to yield results, he explored the possibility of foregoing the support of traditional partners through new or strengthened relations with such alternatives as Libya, China and Saudi Arabia but was again unable to secure the desired partnerships.[46]

Rajoelina's relations with France were characterized by an initial period of gradually increasing diplomatic engagement that weakened after 2012. On 13 May 2011, Andry Rajoelina met with Alain Juppé, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, and was received by the French President Nicolas Sarkozy on 7 December 2011. According to the French presidency, "The interview was devoted to the situation in Madagascar and the completion of the political transition initiated in 2009 through the implementation of the roadmap for the return of constitutional order, validated by the international community".[78] Following Rajoelina's announcement to run in the 2013 election, however, France responded by suspending the visas issued to Rajoelina and his family, and refusing to issue new visas requested by his ministers.[79]

The Rajoelina administration was gradually afforded increasing entry to the United Nations. From 9 to 13 May 2011, Rajoelina was invited to participate in the Fourth United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries, held in Istanbul, Turkey.[80] Rajoelina also spoke during the 66th Session of the United Nations General Assembly which took place on 23 September 2011 in New York City.[81]

2013 presidential candidacy

On 15 January 2013, Rajoelina officially renounced his candidature in the next presidential election, then planned for May 2013. This decision followed a similar declaration on the part of former president Ravalomanana. Exclusion of both political figures from the next general election was a key precondition to international recognition of the elections, as defined by the Southern African Development Community in its roadmap toward ending the political crisis.[82] Rajoelina expressed support for Edgar Razafindravahy, interim mayor of Antananarivo and the official candidate of the TGV party among several other party candidates,[83] and declared his intention to run in the 2018 presidential election.[84]

However, on 3 May 2013, Rajoelina made last-minute arrangements to stand in the 2013 presidential elections, declaring the roadmap agreement had been breached when former president Ravalomanana's wife, Lalao, decided to stand.[85] The candidacy of former president Didier Ratsiraka was also permitted; the candidature of all three prominent politicians was rejected by the international community.[86] At the time that Rajoelina submitted his candidacy, he would have run against forty other candidates in total, of whom seven were affiliated with his own political movement.[87]

The African Union urged Rajoelina, Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka to withdraw their controversial candidacies, and the European Union responded by suspended funding to the election.[86] The French government sanctioned all three candidates by revoking their French visas, effectively barring them from French territory, and considered freezing their financial and real estate assets.[88] Following the suspension of election funding, the HAT again pushed back the election date, citing inadequate financial resources.[86] A special electoral court ruled in August 2013 that the candidatures of Rajoelina, Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka were invalid and that Rajoelina and his two chief rivals would not be permitted to run in the 2013 election. Rajoelina then announced his endorsement of presidential candidate Hery Rajaonarimampianina, who successfully progressed from the first round voting held 25 October 2013 alongside the candidate backed by Ravalomanana, Jean Louis Robinson. The run-off between the two candidates was held on 20 December 2013.[51] Rajaonarimampianina was declared the winner of the election, and Rajoelina officially stepped down on 25 January 2014.[66]

Post-presidency

Following Rajaonarimampianina's election, the international community offered "conditional recognition" of the new government. This tentative validation of the results was motivated by the concern that the new president was a puppet for Rajoelina, as well as the allegations by Robinson of massive electoral fraud after losing the runoff despite a wide lead over his opponent in the first round.[89] Rajaonarimampianina set up the MAPAR committee to organize the selection of his cabinet, a process that extended over several months. During this time, Rajoelina sought to be nominated for the position of Prime Minister of Madagascar and claimed the MAPAR had promised he would be nominated.[90] In April 2014, Rajaonarimampianina instead announced the selection of Roger Kolo,[91] following a consultation round which showed he had support from a majority in the parliament.[92] On 18 April, a cabinet was announced that comprised 31 members with varied political affiliations.[93] Rajoelina qualified Rajaonarimampianina's decision to exclude him and form alliances with the political opposition, including Ravalomanana's supporters, as "hypocrisy and betrayal", and has declared a refusal to seek reconciliation with Rajaonarimampianina.[90]

Following the end of Rajoelina's term, the French government lifted its sanctions against him and 108 other HAT members. He and his family have since maintained a discreet profile, traveling to France, Dubai, South Africa and other foreign destinations. He has also made occasional visits to Madagascar.[94] Rajoelina has declared an interest in presenting himself as a presidential candidate in the 2018 presidential election.[51]

References

- ↑ "Madagascar leader Andry Rajoelina meets Pope Francis". Africa Review. 27 April 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ "Rajoelina père, conseiller de Sunpec". Madagascar Tribune. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Cole, Jennifer (2010). Sex and Salvation: Imagining the Future in Madagascar. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. pp. 180–182. ISBN 9780226113319.

- 1 2 "Rajoelina Andry Nirina: Brève biographie". Madagascar Tribune (in French). 23 March 2009. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Galibert, Didier (March 2009). "Mobilisation populaire et repression a Madagascar: les transgressions de la cite cultuelle" (PDF). Politique africaine (in French). 113: 139–151. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- 1 2 "PORTRAIT – MIALY RAJOELINA: Une femme de ressources". L'Express de l'Ile Maurice (La Sentinelle Limited) (in French). 5 January 2008. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Andry Rajoelina, le roi de l'affichage devenu président" (in French). Africa Intelligence. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ R., A.W. (16 November 2007). "Andry Rajoelina: La foi agissante". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Ramambazafy, Jeannot (12 August 2008). "Viva télévision: Andry Tgv met le turbo" (in French). Madagate. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ Yves, Bernard (17 December 2007). "Andry Rajoelina, nouveau Maire d'Antananarivo élu avec 62% des suffrages". Temoignages (in French). Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Ranamana, M. (5 January 2008). "Lettre des lecteurs : Le trio de 2007 – Rajemison Rakotomaharo, Hery Rafalimanana et Andry Rajoelina". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Randria, N. (22 December 2007). "Andry Rajoelina hérite de 41 milliards fmg de dettes". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Randria, N. (7 January 2008). "La CUA et les coupures d'eau et d'électricité: Antananarivo est-elle sanctionnée?". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ↑ Manjaka, Hery (9 September 2008). "Andry Rajoelina: Les collaborateurs victimes de représailles". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bachelard, Jerome; Marcus, Richard (2011). "Countries at the Crossroads 2011: Madagascar" (PDF). Freedom House. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Madagascar: sortir du cycle de crises. Rapport Afrique N°156" (in French). International Crisis Group. 18 March 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Walt, Vivienne (23 November 2008). "The Breadbasket of South Korea: Madagascar". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ R.C. (17 December 2008). "Andry Rajoelina réunit le "Club des 20"". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Mayor 'takes control' in Madagascar". Al Jazeera. 31 January 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Madagascar sacks capital city mayor". AFP. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Madagascar opposition leader in hiding". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 7 March 2009.

- ↑ "Rajoelina réfugié à l'ambassade de France" (in French). Le Figaro. 10 March 2009.

- ↑ "'Civil war looms' in Madagascar". BBC. 11 March 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ↑ "Report: Madagascan opposition takes financial ministry". People's Daily. Xinhua News Agency. 12 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Madagascar police defy government". BBC. 12 March 2009. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ Lough, Richard (15 March 2009). "Madagascar leader offers referendum to solve crisis". Swissinfo. Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Call to arrest Madagascar leader". BBC. 16 March 2009. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Madagascar soldiers seize palace". BBC. 16 March 2009. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Madagascar: Speech of His Excellency Marc Ravalomanana" (transcript). allAfrica.com. 31 March 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ↑ Lough, Richard (17 March 2009). "Madagascar's president steps down". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Military backs Madagascar rival". BBC. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Madagascar dissolves parliament". Al Jazeera. 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- 1 2 "Foreign diplomats shun swearing-in of Madagascar's president". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 March 2009. Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ↑ "Madagascan navy troops order Rajoelina to leave power in 7 days". People's Daily Online. Xinhua News Agency. 25 March 2009. Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ↑ "Madagascar's Rajoelina sworn in". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 21 March 2009.

- ↑ "Who's your daddy? The youngest political leaders around the world". The Economist. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- 1 2 "Southern African Nations Refuse to Recognize Madagascar Leader". VOA News. 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- 1 2 Tighe, Paul (20 March 2009). "Madagascar Army-Backed Leadership Change Denounced by EU, U.S". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- 1 2 "A coup that is not yet irreversible". The Economist: 56. 28 March – 3 April 2009.

- ↑ Lough, Richard; Iloniaina, Alain (21 March 2009). "Madagascar leader installed, but envoys miss bash". Reuters.

- ↑ "Madagascar president forced out". BBC. 17 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ Lesieur, Alexandra (7 August 2009). "No deal on ousted Madagascar leader's return home: Rajoelina". AFP. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Madagascar parties agree to end political crisis, set election date". English.people.com.cn. People's Daily Online. 14 August 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ ""YES" leading in Madagascar's referendum on new constitution". People's Daily Online. 18 November 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ↑ Zanatsoa, Efra (24 November 2010). "KMF-CNOE: "Des lacunes considérables lors du Référendum."" (in French). La Vérité. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Madagascar: la crise à un tournant critique? Rapport Afrique N°166" (in French). International Crisis Group. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ "Madagascar president forced out". BBC. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Madagascar Approves New Constitution". Voice of America. 21 November 2010. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "The coup that wasn't". The Economist. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- 1 2 Pourtier, Gregoire (21 November 2010). "Madagascar referendum could deepen political crisis". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 Ilioniania, Alain (22 August 2013). "Madagascar pushes back presidential election to October". Reuters. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ Bill (5 March 2013). "Arrivée de l'aide internationale: Andry Rajoelina a tenu à être présent". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Fanjanarivo (14 May 2013). "Subventions énergétiques: Pour les riches et non pas pour les pauvres". La Gazette de la Grande Ile (in French). Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Saraléa, Judicaëlle (6 January 2011). "Produit de première nécessité: Rajoelina promet du riz à Ar 1200". L'Express de Madagascar (in French). Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Rakotoarilala, Ninaivo (11 December 2010). "11 décembre: Jour à marquer d'une pierre blanche pour Andry Rajoelina". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- 1 2 Bill (8 October 2012). "Toamasina: Andry Rajoelina lance de nouveaux défis". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ "Des logements pour les classes moyennes malgaches". Radio France International (in French). 10 September 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ Rakotoarilala, Ninaivo (15 January 2013). "D'Antaninarenina à Ambondrona: Andry Rajoelina revisite son adolescence". Madagascar Tribune (in French). Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ "Lettre ouverte: Pourquoi il faut lever les sanctions économiques contre Madagascar" (in French). Slate Afrique. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- 1 2 De Schutter, Olivier (22 July 2011). "La population malgache a faim car elle est prise en otage" (in French). United Nations. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 Dewar, Bob; Massey, Simon; Baker, Bruce (January 2013). "Madagascar: Time to Make a Fresh Start" (PDF). Chatham House. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Randrianarimanana, Philippe (5 February 2013). "Madagascar: Andry Rajoelina, l'ex-putschiste qui veut être l'élu" (in French). Slate Afrique. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Les dix pays les plus pauvres du monde" (in French). Communiqués de Presse Nations-Unies (ONU). 23 January 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ Fisher, Daniel (5 July 2011). "The World's Worst Economies". Forbes Magazine. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Madagascar: trafic de bois de rose". Le Figaro (in French). 26 December 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- 1 2 Hille, Peter (18 June 2014). "Madagascar's Delicate Democracy". Policy Innovations. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian (21 August 2009). "Lemurs Hunted, Eaten Amid Civil Unrest, Group Says". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Black, Richard (13 July 2012). "Lemurs sliding toward extinction". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Madagascar hit by 'severe' plague of locusts". BBC. 27 March 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Maya Shwayder (26 March 2013). "Locusts in Madagascar: U.N. Needs $41 Million To End The Plague". International Business Times. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Kevin Heath (28 March 2013). "Will Madagascar's wildlife survive the locust plague?". Wildlife News. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "Madagascar sentences ex-president". BBC News. 3 June 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ↑ "Madagascar: Le Boeing de l'ex-président Ravalomanana vendu". Zinfos (in French). 5 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ US Department of State (11 April 2009). "09Antananarivo266: Ravalomanana's Tiko Group under pressure". Leak Overflow. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ "Exiled Madagascan leader Ravalomanana sentenced". BBC News. 28 August 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ↑ "Africans reject Madagascar leader". BBC News. 19 March 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "New Madagascar president is sworn in". Euronews. 21 March 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "France: President Sarkozy meets Rajoelina". Afriquejet.com. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Raharison, Franck (10 June 2013). "Sanctions contre Rajoelina et des ministres: Jusqu'où veut aller la France ?". La Gazette de la Grande Ile (in French). Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "Journal of the United Nations" (PDF). United Nations. 9 May 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "President Andry Nirina Rajoelina of Madagascar addresses the 66th session of the United Nations General Assembly at U.N. headquarters Friday". Yahoo News. 23 September 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Madagascar: Andry Rajoelina renonce à se présenter à la prochaine présidentielle". Radio France International. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Rajoelina / Ravalomanana : Une présidentielle par procuration". L'Observateur. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Madagascar : Andry Rajoelina candidat à la présidentielle de 2018" (in French). Le Monde. 20 January 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Madagascar President Rajoelina to stand in July poll". BBC News. 3 May 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 "United States urges Madagascar to hold free, fair elections". Reuters. 7 June 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Filou, Emilie (18 June 2013). "Lalao Ravalomanana: Madagascar's ex first lady, an undaunted presidential candidate". The Africa Report. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "Madagascar: Andry Rajoelina, Didier Ratsiraka and Ravalomanana Lalao forbidden to reside in France and around the Schengen area". Indian Ocean Times. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "Madagascar: Rajaonarimampianina à l'épreuve" (in French). Indian Ocean Times. 26 February 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Madagascar : Guerre ouverte entre Andry Rajoelina et Hery Rajaonarimampianina" (in French). Indian Ocean Times. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ "Madagascar President Appoints Roger Kolo as Prime Minister". Bloomberg News. 11 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Rabary, Lovasoa; Obulutsa, George (19 April 2014). "Doctor Kolo Roger, new Prime minister of Madagascar". Le Monde. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ "Madagascar: Kolo Roger forme un gouvernement d'ouverture" (in French). Radio France Internationale. 19 April 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ "Madagascar: Andry Rajoelina en famille sur les Champs-Elysées" (in French). Indian Ocean Times. 3 March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Patrick Ramiaramanana |

Mayor of Antananarivo 2007–2009 |

Succeeded by Michele Ratsivalaka |

| Preceded by Marc Ravalomanana as President of Madagascar |

President of the High Transitional Authority of Madagascar 2009–2014 |

Succeeded by Hery Rajaonarimampianina as President of Madagascar |