Anal gland

The anal glands or anal sacs are small glands found near the anus in many mammals, including dogs and cats. They are paired sacs located on either side of the anus between the external and internal sphincter muscles. Sebaceous glands within the lining secrete a liquid that is used for identification of members within a species. These sacs are found in all carnivora, including bears,[1][2] sea otters[3] and kinkajous.[4]

Humans

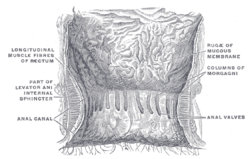

The anal glands are located in the wall of the anal canal. They secrete into the anal canal via anal ducts which open into the anal crypts along the level of the dentate line. The glands themselves are located at varying depths in the anal canal wall, some in between the layers of the internal and external sphincter (the intersphincteric plane). The cryptoglandular theory states that obstruction of these ducts, presumably by accumulation of foreign material (e.g. fecal bacterial plugging) in the crypts, may lead to perianal abscess and fistula formation.[5][6]

Dogs

In dogs, these sacs are occasionally referred to as "scent glands", because they enable the animals to mark their territory and identify other dogs. Most small dogs and many large ones too will need their anal sacs expressed at some stage of their lives. Anal sac expression should be performed to maintain the dog's hygiene, for instance if the fluid leaks spontaneously and to eliminate discomfort. Discomfort is evidenced by the dog dragging its posterior on the ground ("scooting"), licking or biting at the anus, sitting uncomfortably, having difficulty sitting or standing, or chasing its tail. In some dogs the sacs can spontaneously empty, especially under times of stress, and create a very sudden unpleasant change in the odor of the dog. Dog feces are normally firm, and the anal sacs usually empty when the dog defecates. When the dog's stools are soft they may not exert enough pressure on the glands, which then may fail to empty. This may cause discomfort as the full anal sac pushes on the anus. The sacs can be emptied by the dog's keeper, or by a groomer or veterinarian. The sacs are emptied by squeezing the sac so the contents are released through the small openings (ducts) on either side of the anus. This technique is known as anal sac expression. Discomfort may also be evident with impaction or infection of the anal glands. Anal sac impaction results from blockage of the duct leading from the gland to the opening. The sac is usually non-painful and swollen. Anal sac infection results in pain, swelling, and sometimes abscessation and fever. Treatment often involves frequent expression of the sac and systemic antibiotics. Occasionally treatment may include, lancing of an abscess or antibiotic infusion into the gland in the case of infection. The most common bacterial isolates from anal gland infection are E. coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Clostridium perfringens, and Proteus species.[7]

Anal sacs may be removed surgically in a procedure known as anal sacculectomy. This is usually done in the case of recurrent infection or because of the presence of an anal sac adenocarcinoma, a malignant tumor. Potential complications include fecal incontinence (especially when both glands are removed), tenesmus from stricture or scar formation, and persistent draining fistulae.[8]

Anal sac fluid is normally yellow to tan in color and watery in consistency. Impacted anal sac material is usually brown or gray and thick. The presence of blood or pus indicates infection.

Cats

As with dogs, a cat's anal glands can spontaneously empty, especially under times of stress, and create a very sudden unpleasant change in the odor of the cat. A cat's glands may become impacted, causing the cat to defecate outside the litter box, almost anywhere in the house. A veterinarian can empty the clogged glands, and defecating outside the litter box will stop immediately in most cases. Often this problem is incorrectly interpreted as behavioral, when it is entirely a problem of clogged or blocked anal glands or difficulty defecating.

Opossums

Opossums use their anal glands when they "play possum". As the opossum mimics death, the glands secrete a foul-smelling liquid, suggesting the opossum is rotting. Note that opossums are not members of the carnivora, and that their anal sacs differ from those of dogs and their relatives.

Skunks

Skunks use their anal glands to spray a foul-smelling and sticky fluid as a defense against predators.

See also

References

- ↑ Rosell, F.; Jojola, S. M.; Ingdal, K.; Lassen, B. A.; Swenson, J. E.; Arnemo, J. M.; Zedrosser, A. (Feb 2011). "Brown bears possess anal sacs and secretions may code for sex". Journal of Zoology. 283 (2): 143–152. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00754.x.

- ↑ Dyce, K.M.; Sack, W.O.; Wensing, C.J.G. (1987). Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy. W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-1332-2.

- ↑ Kenyon, Karl W. (1969). The Sea Otter in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife.

- ↑ Ford, L. S.; Hoffman, R. S. (1988-12-27). "Potos flavus". Mammalian Species. American Society of Mammalogists. 321: 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504086. JSTOR 3504086.

- ↑ Yamada, Tadataka; Alpers, David H.; Kalloo, Anthony N.; Kaplowitz, Neil; Owyang, Chung; Powell, Don W., eds. (2009). Textbook of gastroenterology (5th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-1-4051-6911-0.

- ↑ Wolff, Bruce G.; Pemberton, John H.; Wexner, Steven D.; Fleshman, James W.; Beck, David E., eds. (2007). The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-24846-3.

- ↑ Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.

- ↑ Hill LM, Smeak DD (2002). "Open versus closed bilateral anal sacculectomy for treatment of non-neoplastic anal sac disease in dogs: 95 cases (1969–1994)". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 221 (5): 662–5. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.221.662. PMID 12216905.