An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction

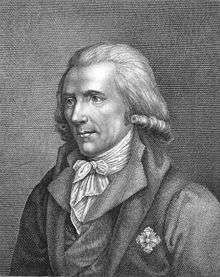

An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction (1798), which was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, is a scientific paper by Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford that provided a substantial challenge to established theories of heat and began the 19th century revolution in thermodynamics.

Background

Rumford was an opponent of the caloric theory of heat which held that heat was a fluid that could be neither created nor destroyed. He had further developed the view that all gases and liquids were absolute non-conductors of heat. His views were out of step with the accepted science of the time and the latter theory had particularly been attacked by John Dalton and John Leslie.

Rumford was heavily influenced by the argument from design and it is likely that he wished to grant water a privileged and providential status in the regulation of human life.

Though Rumford was to come to associate heat with motion, there is no evidence that he was committed to the kinetic theory or the principle of vis viva.

In his 1798 paper, Rumford acknowledged that he had predecessors in the notion that heat was a form of motion. Those predecessors included Francis Bacon, Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, John Locke, and Henry Cavendish.

Experiments

Rumford had observed the frictional heat generated by boring cannon at the arsenal in Munich. Rumford immersed a cannon barrel in water and arranged for a specially blunted boring tool. He showed that the water could be boiled within roughly two and a half hours and that the supply of frictional heat was seemingly inexhaustible. Rumford confirmed that no physical change had taken place in the material of the cannon by comparing the specific heats of the material machined away and that remaining were the same.

Rumford argued that the seemingly indefinite generation of heat was incompatible with the caloric theory. He contended that the only thing communicated to the barrel was motion.

Rumford made no attempt to further quantify the heat generated or to measure the mechanical equivalent of heat.

Reception

.png)

Most established scientists, such as William Henry, as well as Thomas Thomson, believed that there was enough uncertainty in the caloric theory to allow its adaptation to account for the new results. It had certainly proved robust and adaptable up to that time. Furthermore, Thomson, Jöns Jakob Berzelius, and Antoine César Becquerel observed that electricity could be indefinitely generated by friction. No educated scientist of the time was willing to hold that electricity was not a fluid.

Ultimately, Rumford's claim of the "inexhaustible" supply of heat was a reckless extrapolation from the study. Charles Haldat made some penetrating criticisms of the reproducibility of Rumford's results and it is possible to see the whole experiment as somewhat tendentious.

However, the experiment inspired the work of James Prescott Joule in the 1840s. Joule's more exact measurements were pivotal in establishing the kinetic theory at the expense of caloric.

Notes

- ^ Benjamin Count of Rumford (1798) "An inquiry concerning the source of the heat which is excited by friction," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 88 : 80–102. doi:10.1098/rstl.1798.0006

- ^ Cardwell (1971) p.99

- ^ Leslie, J. (1804). An Experimental Enquiry into the Nature and Propagation of Heat. London.

- ^ Rumford (1804) "An enquiry concerning the nature of heat and the mode of its communication" Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society p.77

- ^ Cardwell (1971) pp99-100

- ^ From p. 100 of Rumford's paper of 1798: "Before I finish this paper, I would beg leave to observe, that although, in treating the subject I have endeavoured to investigate, I have made no mention of the names of those who have gone over the same ground before me, nor of the success of their labours; this omission has not been owing to any want of respect for my predecessors, but was merely to avoid prolixity, and to be more at liberty to pursue, without interruption, the natural train of my own ideas."

- ^ In his Novum Organum (1620), Francis Bacon concludes that heat is the motion of the particles composing matter. In Francis Bacon, Novum Organum (London, England: William Pickering, 1850), from page 164: " … Heat appears to be Motion." From p. 165: " … the very essence of Heat, or the Substantial self of Heat, is motion and nothing else, … " From p. 168: " … Heat is not a uniform Expansive Motion of the whole, but of the small particles of the body; … "

- ^ "Of the mechanical origin of heat and cold" in: Robert Boyle, Experiments, Notes, &c. About the Mechanical Origine or Production of Divers Particular Qualities: … (London, England: E. Flesher (printer), 1675). At the conclusion of Experiment VI, Boyle notes that if a nail is driven completely into a piece of wood, then further blows with the hammer cause it to become hot as the hammer's force is transformed into random motion of the nail's atoms. From pp. 61-62: " … the impulse given by the stroke, being unable either to drive the nail further on, or destroy its interness [i.e., entireness, integrity], must be spent in making various vehement and intestine commotion of the parts among themselves, and in such an one we formerly observed the nature of heat to consist."

- ^ "Lectures of Light" (May 1681) in: Robert Hooke with R. Waller, ed., The Posthumous Works of Robert Hooke … (London, England: Samuel Smith and Benjamin Walford, 1705). From page 116: "Now Heat, as I shall afterward prove, is nothing but the internal Motion of the Particles of [a] Body; and the hotter a Body is, the more violently are the Particles moved, … "

- ^ Sometime during the period 1698-1704, John Locke wrote his book Elements of Natural Philosophy, which was first published in 1720: John Locke with Pierre Des Maizeaux, ed., A Collection of Several Pieces of Mr. John Locke, Never Before Printed, Or Not Extant in His Works (London, England: R. Francklin, 1720). From p. 224: "Heat, is a very brisk agitation of the insensible parts of the object, which produces in us that sensation, from whence we denominate the object hot: so what in our sensation is heat, in the object is nothing but motion. This appears by the way, whereby heat is produc'd: for we see that the rubbing of a brass-nail upon a board, will make it very hot; and the axle-trees of carts and coaches are often hot, and sometimes to a degree, that it sets them on fire, by rubbing of the nave of the wheel upon it."

- ^ Henry Cavendish (1783) "Observations on Mr. Hutchins's experiments for determining the degree of cold at which quicksilver freezes," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 73 : 303-328. From the footnote continued on p. 313: " … I think Sir Isaac Newton's opinion, that heat consists in the internal motion of the particles of bodies, much the most probable … "

- ^ Henry, W. (1802) "A review of some experiments which have been supposed to disprove the materiality of heat", Manchester Memoirs v, p.603

- ^ Thomson, T. "Caloric", Supplement on Chemistry, Encyclopædia Britannica, 3rd ed.

- ^ Haldat, C.N.A (1810) "Inquiries concerning the heat produced by friction", Journal de Physique lxv, p.213

- ^ Cardwell (1971) p.102

Bibliography

- Cardwell, D.S.L. (1971). From Watt to Clausius: The Rise of Thermodynamics in the Early Industrial Age. Heinemann: London. ISBN 0-435-54150-1.