Amaranth (dye)

| |

_ball-and-stick.png) | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

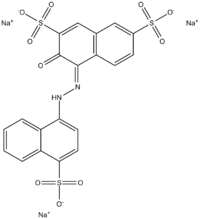

| IUPAC name

Trisodium (4E)-3-oxo-4-[(4-sulfonato-1-naphthyl)hydrazono]naphthalene-2,7-disulfonate | |

| Other names

FD&C Red No. 2, E123, C.I. Food Red 9, Acid Red 27, Azorubin S, C.I. 16185 | |

| Identifiers | |

| 915-67-3 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChemSpider | 21169821 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.011.839 |

| E number | E123 (colours) |

| PubChem | 6093196 |

| UNII | 37RBV3X49K |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C20H11N2Na3O10S3 | |

| Molar mass | 604.47305 |

| Appearance | Dark red solid |

| Melting point | 120 °C (248 °F; 393 K) (decomposes) |

| Hazards | |

| R-phrases | R36/37/38 |

| S-phrases | S36/37/39 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Amaranth, FD&C Red No. 2, E123, C.I. Food Red 9, Acid Red 27, Azorubin S, or C.I. 16185 is a dark red to purple azo dye used as a food dye and to color cosmetics. The name was taken from amaranth grain, a plant distinguished by its red color and edible protein-rich seeds.

Amaranth is an anionic dye. It can be applied to natural and synthetic fibers, leather, paper, and phenol-formaldehyde resins. As a food additive it has E number E123. Amaranth usually comes as a trisodium salt. It has the appearance of reddish-brown, dark red to purple water-soluble powder that decomposes at 120 °C without melting. Its water solution has absorption maximum at about 520 nm. Like all azo dyes, Amaranth was, during the middle of the 20th century, made from coal tar; modern synthetics are more likely to be made from petroleum byproducts.[1][2]

Since 1976 Amaranth has been banned in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)[3] as a suspected carcinogen.[4][5] Its use is still legal in some countries, notably in the United Kingdom where it is most commonly used to give Glacé cherries their distinctive color.

History and health effects

After an incident in 1954 involving FD&C Orange Number 1,[6][7] the FDA retested food colors. In 1960 the FDA was given jurisdiction over color additives, limiting the amounts that could be added to foods and requiring producers of food color to ensure safety and proper labeling of colors. Permission to use food additives was given on a provisional basis, which could be withdrawn should safety issues arise.[7] The FDA gave "generally recognized as safe" (GRAS) provisional status to substances already in use, and extended Red No. 2's provisional status 14 times.

In 1971 a Soviet study linked the dye to cancer.[8][7] By 1976 over 1 million pounds of the dye worth $5 million was used as a colorant in $10 billion worth of foods, drugs and cosmetics.[9] Consumer activists in the United States, perturbed by what they perceived as collusion between the FDA and food conglomerates,[10] put pressure on the FDA to ban it.[9] FDA Commissioner Alexander Schmidt defended the dye in spite of all the evidence, as he had earlier defended the FDA against collusion accusations in his 1975 book, stating that the FDA found "no evidence of a public health hazard".[9] Testing by the FDA found a statistically significant increase in the incidence of malignant tumors in female rats given a high dosage of the dye,[7] and concluded that since there could also no longer be a presumption of safety, that use of the dye should be discontinued.[7] The FDA banned FD&C Red No. 2 in 1976.[9][11] FD&C Red No. 40 (Allura Red AC) replaced the banned Red No. 2.

See also

References

- ↑ "Amaranth E123". LOOKCUT, INC. 2004–2010. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ↑ "Aniline Wood Dye, Coal Tar Dyes". Craftsman Style. International Styles Network. 2005–2012. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ↑ Compliance Program Guidance Manual: Domestic Food Safety (FY07-08) (PDF), Food and Drug Administration, November 9, 2008, p. 6,

Be award that the following color additives are not on the list for use in food products in the United States. a. Amaranth (C.I. 16185, EEC No E123, formerly certifiable as FD&C Red No 2)

- ↑ Color Additives Fact Sheet, U. S. Food and Drug Administration's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, July 30, 2001, archived from the original on November 17, 2001

- ↑ OVERVIEW OF FOOD COLOR ADDITIVES, Prepared for the USDA National Organic Program and the National Organic Standards Board, Agricultural Marketing Service (United States Department of Agriculture), October 14, 2005, pp. 1 and 7, retrieved August 15, 2014

- ↑ Science News Letter, Volumes 65-66. Science Service. January 30, 1954. p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Omaye, Stanley T. (2004). Food and Nutritional Toxicology. CRC Press LLC. p. 257. ISBN 0-203-48530-0.

- ↑ "Why Red M&M's Disappeared for a Decade". Pricenomics. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- 1 2 3 4 "Death of a Dye". TIME magazine. February 2, 1976. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Greenberg, Dan (4 December 1975). "Washington View: FDA in difficulties". New Scientist. London: New Science Publications. 64 (978): 600.

- ↑ "Burger Backs Red Dye Ban Pending Rule". The Hartford Courant. February 14, 1976. Retrieved 2009-07-07.