Amalrician

The Amalricians were a pantheist, free love[1] movement named after Amalric of Bena. The beliefs are thought to have influenced the Brethren of the Free Spirit.

The beginnings of medieval pantheistic Christian theology lie in the early 13th century, with theologians at Paris, such as David of Dinant, Amalric of Bena, and Ortlieb of Strassburg, and was later mixed with the millenarist theories of Gioacchino da Fiore.

Fourteen followers of Amalric began to preach that "all things are One, because whatever is, is God." They believed that after the age of the Father (the Patriarchal Age) and the age of the Son (Christianity), a new age of the Holy Spirit was at hand.[2] The Amalricians, who included many priests and clerics, succeeded for some time in propagating their beliefs without being detected by the ecclesiastical authorities.

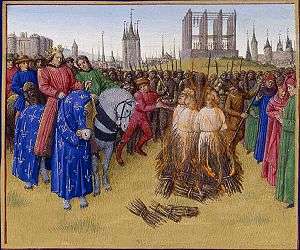

In 1210, Peter of Nemours, Bishop of Paris, and the Chevalier Guérin, an adviser to the French King Philip II Augustus, obtained secret information from an undercover agent called Master Ralph. This intelligence gathered laid bare the inner workings of the sect, enabling authorities to arrest its principals and proselytes. That same year, a council of bishops and doctors from the University of Paris assembled to take measures for the punishment of the offenders. The ignorant converts, including many women, were pardoned. Of the principals, four were condemned to imprisonment for life. Ten members were burned at the stake.[3]

Almaric was posthumously subjected to the persecution. Besides being included in the condemnation of his disciples, a special sentence of excommunication was pronounced against him in the council of 1210, and his bones were exhumed from their resting-place and cast into unconsecrated ground.[4] The doctrine was condemned again by Pope Innocent III in the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) "as insanity rather than heresy", and in 1225 Pope Honorius III condemned the work of Johannes Scotus Eriugena, De Divisione Naturæ, from which Amalric was supposed to have derived the beginnings of his heresy.[5]

The movement survived, however, and later followers went even further, arguably evolving into the Brethren of the Free Spirit.

References

- ↑ History of the Christian philosophy of religion from the Reformation to Kant

- ↑ COHN, N. The Pursuit of the Millennium : Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, 1970, page 155.

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Amalricians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Amalricians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Amalricians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Amalricians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Amalricians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Amalricians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.