Almagest

The work known as the Almagest, named in Greek Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις (Mathēmatikē Syntaxis), and also called the Syntaxis Mathematica, is a 2nd-century Greek mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy (Greek: Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος, Klaúdios Ptolemaîos; c. AD 100 – c. 170). One of the most influential scientific texts of all time, its geocentric model was accepted for more than 1200 years from its origin in Hellenistic Alexandria, in the medieval Byzantine and Islamic worlds, and in Western Europe through the Middle Ages and early Renaissance until Copernicus.

The Almagest is the critical source of information on ancient Greek astronomy. It has also been valuable to students of mathematics because it documents the ancient Greek mathematician Hipparchus's work, which has been lost. Hipparchus wrote about trigonometry, but because his works appear to have been lost, mathematicians use Ptolemy's book as their source for Hipparchus's work and ancient Greek trigonometry in general.

The treatise was later titled Hē Megalē Syntaxis (Ἡ Μεγάλη Σύνταξις, "The Great Treatise"; Latin: Magna Syntaxis), and the superlative form of this (Ancient Greek: μεγίστη, megiste, "greatest") lies behind the Arabic name al-majisṭī (المجسطي), from which the English name Almagest derives. The Arabic name is important due to the popularity of a Latin re-translation made in the 12th century from an Arabic translation, which would endure until original Greek copies resurfaced in the 15th century.

Ptolemy set up a public inscription at Canopus, Egypt, in 147 or 148. The late N. T. Hamilton found that the version of Ptolemy's models set out in the Canopic Inscription was earlier than the version in the Almagest. Hence it cannot have been completed before about 150, a quarter century after Ptolemy began observing.[1]

Contents

Books

The Syntaxis Mathematica or Almagest (Almagestum) consists of thirteen sections, called books. As with many medieval manuscripts that were handcopied or, particularly, printed in the early years of printing, there were considerable differences between various editions of the same text, as the process of transcription was highly personal. An example illustrating how the Syntaxis was organized is given below. It is a 152-page Latin edition printed in 1515 at Venice by Petrus Lichtenstein.[2]

- Book I contains an outline of Aristotle's cosmology: on the spherical form of the heavens, with the spherical Earth lying motionless as the center, with the fixed stars and the various planets revolving around the Earth. Then follows an explanation of chords with table of chords; observations of the obliquity of the ecliptic (the apparent path of the Sun through the stars); and an introduction to spherical trigonometry.

- Book II covers problems associated with the daily motion attributed to the heavens, namely risings and settings of celestial objects, the length of daylight, the determination of latitude, the points at which the Sun is vertical, the shadows of the gnomon at the equinoxes and solstices, and other observations that change with the spectator's position. There is also a study of the angles made by the ecliptic with the vertical, with tables.

- Book III covers the length of the year, and the motion of the Sun. Ptolemy explains Hipparchus' discovery of the precession of the equinoxes and begins explaining the theory of epicycles.

- Books IV and V cover the motion of the Moon, lunar parallax, the motion of the lunar apogee, and the sizes and distances of the Sun and Moon relative to the Earth.

- Book VI covers solar and lunar eclipses.

- Books VII and VIII cover the motions of the fixed stars, including precession of the equinoxes. They also contain a star catalogue of 1022 stars, described by their positions in the constellations. The brightest stars were marked first magnitude (m = 1), while the faintest visible to the naked eye were sixth magnitude (m = 6). Each numerical magnitude was twice the brightness of the following one, which is a logarithmic scale. This system is believed to have originated with Hipparchus. The stellar positions too are of Hipparchan origin, despite Ptolemy's claim to the contrary.

- Book IX addresses general issues associated with creating models for the five naked eye planets, and the motion of Mercury.

- Book X covers the motions of Venus and Mars.

- Book XI covers the motions of Jupiter and Saturn.

- Book XII covers stations and retrograde motion, which occurs when planets appear to pause, then briefly reverse their motion against the background of the zodiac. Ptolemy understood these terms to apply to Mercury and Venus as well as the outer planets.

- Book XIII covers motion in latitude, that is, the deviation of planets from the ecliptic.

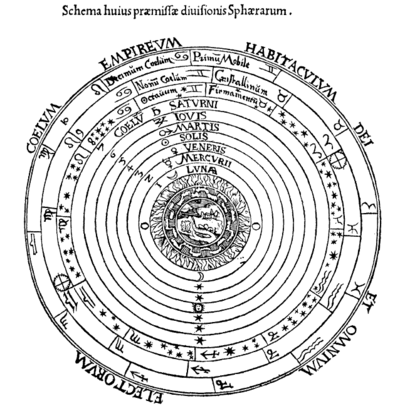

Ptolemy's cosmos

The cosmology of the Syntaxis includes five main points, each of which is the subject of a chapter in Book I. What follows is a close paraphrase of Ptolemy's own words from Toomer's translation.[3]

- The celestial realm is spherical, and moves as a sphere.

- The Earth is a sphere.

- The Earth is at the center of the cosmos.

- The Earth, in relation to the distance of the fixed stars, has no appreciable size and must be treated as a mathematical point.[4]

- The Earth does not move.

Ptolemy's planetary model

Ptolemy assigned the following order to the planetary spheres, beginning with the innermost:

- Moon

- Mercury

- Venus

- Sun

- Mars

- Jupiter

- Saturn

- Sphere of fixed stars

Other classical writers suggested different sequences. Plato (c. 427 – c. 347 BC) placed the Sun second in order after the Moon. Martianus Capella (5th century AD) put Mercury and Venus in motion around the Sun. Ptolemy's authority was preferred by most medieval Islamic and late medieval European astronomers.

Ptolemy inherited from his Greek predecessors a geometrical toolbox and a partial set of models for predicting where the planets would appear in the sky. Apollonius of Perga (c. 262 – c. 190 BC) had introduced the deferent and epicycle and the eccentric deferent to astronomy. Hipparchus (2nd century BC) had crafted mathematical models of the motion of the Sun and Moon. Hipparchus had some knowledge of Mesopotamian astronomy, and he felt that Greek models should match those of the Babylonians in accuracy. He was unable to create accurate models for the remaining five planets.

The Syntaxis adopted Hipparchus' solar model, which consisted of a simple eccentric deferent. For the Moon, Ptolemy began with Hipparchus' epicycle-on-deferent, then added a device that historians of astronomy refer to as a "crank mechanism":[5] He succeeded in creating models for the other planets, where Hipparchus had failed, by introducing a third device called the equant.

Ptolemy wrote the Syntaxis as a textbook of mathematical astronomy. It explained geometrical models of the planets based on combinations of circles, which could be used to predict the motions of celestial objects. In a later book, the Planetary Hypotheses, Ptolemy explained how to transform his geometrical models into three-dimensional spheres or partial spheres. In contrast to the mathematical Syntaxis, the Planetary Hypotheses is sometimes described as a book of cosmology.

Impact

Ptolemy's comprehensive treatise of mathematical astronomy superseded most older texts of Greek astronomy. Some were more specialized and thus of less interest; others simply became outdated by the newer models. As a result, the older texts ceased to be copied and were gradually lost. Much of what we know about the work of astronomers like Hipparchus comes from references in the Syntaxis.

The first translations into Arabic were made in the 9th century, with two separate efforts, one sponsored by the caliph Al-Ma'mun. Sahl ibn Bishr is thought to be the first Arabic translator. By this time, the Syntaxis was lost in Western Europe, or only dimly remembered. Henry Aristippus made the first Latin translation directly from a Greek copy, but it was not as influential as a later translation into Latin made by Gerard of Cremona from the Arabic. Gerard translated the Arabic text while working at the Toledo School of Translators, although he was unable to translate many technical terms such as the Arabic Abrachir for Hipparchus. In the 12th century a Spanish version was produced, which was later translated under the patronage of Alfonso X.

In the 15th century, a Greek version appeared in Western Europe. The German astronomer Johannes Müller (known, from his birthplace of Königsberg, as Regiomontanus) made an abridged Latin version at the instigation of the Greek churchman Johannes, Cardinal Bessarion. Around the same time, George of Trebizond made a full translation accompanied by a commentary that was as long as the original text. George's translation, done under the patronage of Pope Nicholas V, was intended to supplant the old translation. The new translation was a great improvement; the new commentary was not, and aroused criticism. The Pope declined the dedication of George's work, and Regiomontanus's translation had the upper hand for over 100 years.

During the 16th century, Guillaume Postel, who had been on an embassy to the Ottoman Empire, brought back Arabic disputations of the Almagest, such as the works of al-Kharaqī, Muntahā al-idrāk fī taqāsīm al-aflāk ("The Ultimate Grasp of the Divisions of Spheres", 1138/9).[6]

Commentaries on the Syntaxis were written by Theon of Alexandria (extant), Pappus of Alexandria (only fragments survive), and Ammonius Hermiae (lost).

Modern editions

The Syntaxis was edited by J. L. Heiberg in Claudii Ptolemaei opera quae exstant omnia, vols. 1.1 and 1.2 (1898, 1903).

Two translations of the Syntaxis into English have been published . The first, by R. Catesby Taliaferro of St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland, was included in volume 16 of the Great Books of the Western World; the second, by G. J. Toomer, Ptolemy's Almagest in 1984, with a second edition in 1998.[3]

A direct French translation from the Greek text was published in two volumes in 1813 and 1816 by Nicholas Halma, including detailed historical comments in a 69-page preface. The scanned books are available in full at the Gallica French national library.[7][8]

Gallery

-

Ptolemy's cataloque of stars; a revision of the Syntaxis by Christian Heinrich Friedrich Peters and Edward Ball Knobel, 1915

-

Epytoma Ioannis de Monte Regio in Almagestum Ptolomei, Latin, 1496

-

Almagestum, Latin, 1515

Footnotes

- ↑ NT Hamilton, N. M. Swerdlow, G. J. Toomer. "The Canobic Inscription: Ptolemy's Earliest Work". In Berggren and Goldstein, eds., From Ancient Omens to Statistical Mechanics. Copenhagen: University Library, 1987.

- ↑ "Almagestum (1515)". Universität Wien. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- 1 2 Toomer, G. J. (1998), Ptolemy's Almagest, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-00260-6

- ↑ Ptolemy. Almagest., Book I, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Michael Hoskin. The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Chapter 2, page 44.

- ↑ Islamic science and the making of European Renaissance, by George Saliba, p.218 ISBN 978-0-262-19557-7

- ↑ Halma, Nicolas (1813). Composition mathématique de Claude Ptolémée, traduite pour la première fois du grec en français, sur les manuscrits originaux de la bibliothèque impériale de Paris, tome 1 (in French). Paris: J. Hermann. p. 608.

- ↑ Halma, Nicolas (1816). Composition mathématique de Claude Ptolémée, ou astronomie ancienne, traduite pour la première fois du grec en français sur les manuscrits de la bibliothèque du roi, tome 2 (in French). Paris: H. Grand. p. 524.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Almagest. |

- Abū al-Wafā' Būzjānī (who also wrote an Almagest)

- Book of Fixed Stars

- Star cartography

References

- James Evans, The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy, Oxford University Press, 1998 (ISBN 0-19-509539-1)

- Michael Hoskin, The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy, Cambridge University Press, 1999 (ISBN 0-521-57291-6)

- Olaf Pedersen, A Survey of the Almagest, Odense University Press, 1974 (ISBN 87-7492-087-1. A revised edition, prepared by Alexander Jones, is due to be published by Springer on November 29, 2010.

- Olaf Pedersen, Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press, 1993 (ISBN 0-521-40340-5)

External links

- Ptolemy. Almagest. Latin translation from the Arabic by Gerard of Cremona. Digitized version of manuscript made in Northern Italy c. 1200-1225 held by the State Library of Victoria.

- University of Vienna: Almagestum (1515) PDF:s of different resolutions. (Latin)

- Almagest Planetary Model Animations

- Online luni-solar and planetary ephemeris calculator based on the Almagest

- Ptolemy's Almagest. PDF scans of Heiberg's Greek edition, now in the public domain (Classical Greek)

- A podcast discussion by Prof. M Heath and Dr A. Chapman of a recent re-discovery of a 14th-century manuscript in the university of Leeds Library

- Star catalog in ASCII (Latin)