Albertus Magnus

| Saint Albertus Magnus, O.P. | |

|---|---|

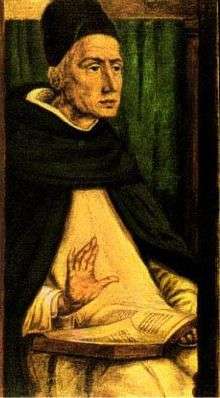

Saint Albertus Magnus, a fresco by Tommaso da Modena (1352), Church of San Nicolò, Treviso, Italy | |

| Religious, Bishop, and Doctor of the Church | |

| Born |

c. 1200 Lauingen, Duchy of Bavaria |

| Died |

November 15, 1280 Cologne, Holy Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 1622, Rome, Papal States, by Pope Gregory XV |

| Canonized | 1931, Vatican City, by Pope Pius XI |

| Major shrine | St. Andrew's Church, Cologne, Germany |

| Feast | November 15 |

| Patronage | Cincinnati, Ohio; medical technicians; natural sciences; philosophers; scientists; students |

| Albertus Magnus | |

|---|---|

| Born |

c. 1200 Lauingen |

| Died |

1280 Cologne |

| Other names | Albertus Teutonicus, Albertus Coloniensis, Albert the Great, Albert of Cologne |

| Alma mater | University of Padua |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

Scholasticism Medieval realism[1] |

|

Influences

| |

|

Influenced

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

| Branches |

|

|

Albertus Magnus,[3] O.P. (c. 1200 – November 15, 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar and Catholic bishop. Later canonised as a Catholic saint, he was known during his lifetime as doctor universalis and doctor expertus and, late in his life, the term magnus was appended to his name.[4] Scholars such as James A. Weisheipl and Joachim R. Söder have referred to him as the greatest German philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages.[5] The Catholic Church distinguishes him as one of the 36 Doctors of the Church.

Biography

It seems likely that Albert was born sometime before 1200, given well-attested evidence that he was aged over 80 on his death in 1280. More than one source says that Albert was 87 on his death, which has led 1193 to be commonly given as the date of Albert's birth.[6] Albert was probably born in Lauingen (now in Bavaria), since he called himself 'Albert of Lauingen', but this might simply be a family name. Most probably his family was of ministerial class; his familiar connection with (being son of the count) Bollstädt noble family was a 15th-century misinterpretation that is now completely disproved.[6]

Albert was probably educated principally at the University of Padua, where he received instruction in Aristotle's writings. A late account by Rudolph de Novamagia refers to Albertus' encounter with the Blessed Virgin Mary, who convinced him to enter Holy Orders. In 1223 (or 1229)[7] he became a member of the Dominican Order, and studied theology at Bologna and elsewhere. Selected to fill the position of lecturer at Cologne, Germany, where the Dominicans had a house, he taught for several years there, as well as in Regensburg, Freiburg, Strasbourg, and Hildesheim. During his first tenure as lecturer at Cologne, Albert wrote his Summa de bono after discussion with Philip the Chancellor concerning the transcendental properties of being.[8] In 1245, Albert became master of theology under Gueric of Saint-Quentin, the first German Dominican to achieve this distinction. Following this turn of events, Albert was able to teach theology at the University of Paris as a full-time professor, holding the seat of the Chair of Theology at the College of St. James.[8][9] During this time Thomas Aquinas began to study under Albertus.[10]

Albert was the first to comment on virtually all of the writings of Aristotle, thus making them accessible to wider academic debate. The study of Aristotle brought him to study and comment on the teachings of Muslim academics, notably Avicenna and Averroes, and this would bring him into the heart of academic debate.

In 1254 Albert was made provincial of the Dominican Order,[10] and fulfilled the duties of the office with great care and efficiency. During his tenure he publicly defended the Dominicans against attacks by the secular and regular faculty of the University of Paris, commented on St. John, and answered what he perceived as errors of the Islamic philosopher Averroes.

In 1259 Albert took part in the General Chapter of the Dominicans at Valenciennes together with Thomas Aquinas, masters Bonushomo Britto,[11] Florentius,[12] and Peter (later Pope Innocent V) establishing a ratio studiorum or program of studies for the Dominicans[13] that featured the study of philosophy as an innovation for those not sufficiently trained to study theology. This innovation initiated the tradition of Dominican scholastic philosophy put into practice, for example, in 1265 at the Order's studium provinciale at the convent of Santa Sabina in Rome, out of which would develop the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, the "Angelicum"[14]

In 1260 Pope Alexander IV made him bishop of Regensburg, an office from which he resigned after three years. During the exercise of his duties he enhanced his reputation for humility by refusing to ride a horse, in accord with the dictates of the Order, instead traversing his huge diocese on foot. This earned him the affectionate sobriquet "boots the bishop" from his parishioners. In 1263 Pope Urban IV relieved him of the duties of bishop and asked him to preach the eighth Crusade in German-speaking countries.[15] After this, he was especially known for acting as a mediator between conflicting parties. In Cologne he is not only known for being the founder of Germany's oldest university there, but also for "the big verdict" (der Große Schied) of 1258, which brought an end to the conflict between the citizens of Cologne and the archbishop. Among the last of his labors was the defense of the orthodoxy of his former pupil, Thomas Aquinas, whose death in 1274 grieved Albert (the story that he travelled to Paris in person to defend the teachings of Aquinas can not be confirmed).

After suffering a collapse of health in 1278, he died on November 15, 1280, in the Dominican convent in Cologne, Germany. Since November 15, 1954, his relics are in a Roman sarcophagus in the crypt of the Dominican St. Andreas Church in Cologne.[16] Although his body was discovered to be incorrupt at the first exhumation three years after his death, at the exhumation in 1483 only a skeleton remained.[17]

Albert was beatified in 1622. He was canonized and proclaimed a Doctor of the Church on December 16, 1931, by Pope Pius XI[15] and the patron saint of natural scientists in 1941. St. Albert's feast day is November 15.

Writings

Albert's writings collected in 1899 went to thirty-eight volumes. These displayed his prolific habits and encyclopedic knowledge of topics such as logic, theology, botany, geography, astronomy, astrology, mineralogy, alchemy, zoology, physiology, phrenology, justice, law, friendship, and love. He digested, interpreted, and systematized the whole of Aristotle's works, gleaned from the Latin translations and notes of the Arabian commentators, in accordance with Church doctrine. Most modern knowledge of Aristotle was preserved and presented by Albert.[10]

His principal theological works are a commentary in three volumes on the Books of the Sentences of Peter Lombard (Magister Sententiarum), and the Summa Theologiae in two volumes. The latter is in substance a more didactic repetition of the former.

Albert's activity, however, was more philosophical than theological (see Scholasticism). The philosophical works, occupying the first six and the last of the 21 volumes, are generally divided according to the Aristotelian scheme of the sciences, and consist of interpretations and condensations of Aristotle's relative works, with supplementary discussions upon contemporary topics, and occasional divergences from the opinions of the master. Albert believed that Aristotle's approach to natural philosophy did not pose any obstacle to the development of a Christian philosophical view of the natural order.[15]

Albert's knowledge of physical science was considerable and for the age remarkably accurate. His industry in every department was great, and though we find in his system many gaps which are characteristic of scholastic philosophy, his protracted study of Aristotle gave him a great power of systematic thought and exposition. An exception to this general tendency is his Latin treatise "De falconibus" (later inserted in the larger work, De Animalibus, as book 23, chapter 40), in which he displays impressive actual knowledge of a) the differences between the birds of prey and the other kinds of birds; b) the different kinds of falcons; c) the way of preparing them for the hunt; and d) the cures for sick and wounded falcons.[18] His scholarly legacy justifies his contemporaries' bestowing upon him the honourable surname Doctor Universalis.

In De Mineralibus Albert claims, "The aim of natural philosophy (science) is not simply to accept the statements of others, but to investigate the causes that are at work in nature." Aristotelianism greatly influences Albert's view on nature and philosophy.[10] Another example of his reason to formally search for the causes is in his treatises on plants, he begins with the principle, experiment is the only safe guide in such investigations. His studies of Aristotle and theology show their colors in nearly all of his works and volumes.

Albert placed emphasis on experiment as well as investigation, but he respected authority and tradition so much that many of his investigations or experiments were unpublished. Albert would often keep silent about many issues such as astronomy, physics and such because he felt that his theories were too advanced for the time in which he was living.[10]

Alchemy

In the centuries since his death, many stories arose about Albert as an alchemist and magician. "Much of the modern confusion results from the fact that later works, particularly the alchemical work known as the Secreta Alberti or the Experimenta Alberti, were falsely attributed to Albertus by their authors to increase the prestige of the text through association."[19] On the subject of alchemy and chemistry, many treatises relating to alchemy have been attributed to him, though in his authentic writings he had little to say on the subject, and then mostly through commentary on Aristotle. For example, in his commentary, De mineralibus, he refers to the power of stones, but does not elaborate on what these powers might be.[20] A wide range of Pseudo-Albertine works dealing with alchemy exist, though, showing the belief developed in the generations following Albert's death that he had mastered alchemy, one of the fundamental sciences of the Middle Ages. These include Metals and Materials; the Secrets of Chemistry; the Origin of Metals; the Origins of Compounds, and a Concordance which is a collection of Observations on the philosopher's stone; and other alchemy-chemistry topics, collected under the name of Theatrum Chemicum.[21] He is credited with the discovery of the element arsenic[22] and experimented with photosensitive chemicals, including silver nitrate.[23][24] He did believe that stones had occult properties, as he related in his work De mineralibus. However, there is scant evidence that he personally performed alchemical experiments.

According to legend, Albert is said to have discovered the philosopher's stone and passed it on to his pupil Thomas Aquinas, shortly before his death. Albert does not confirm he discovered the stone in his writings, but he did record that he witnessed the creation of gold by "transmutation."[25] Given that Thomas Aquinas died six years before Albert's death, this legend as stated is unlikely.

Astrology

Albert was deeply interested in astrology, as has been articulated by scholars such as Paola Zambelli.[26] Throughout the Middle Ages –and well into the early modern period –astrology was widely accepted by scientists and intellectuals who held the view that life on earth is effectively a microcosm within the macrocosm (the latter being the cosmos itself). It was believed that correspondence therefore exists between the two and thus the celestial bodies follow patterns and cycles analogous to those on earth. With this worldview, it seemed reasonable to assert that astrology could be used to predict the probable future of a human being. Albert made this a central component of his philosophical system, arguing that an understanding of the celestial influences affecting us could help us to live our lives more in accord with Christian precepts.[27] The most comprehensive statement of his astrological beliefs is to be found in a work he authored around 1260, now known as the Speculum astronomiae. However, details of these beliefs can be found in almost everything he wrote, from his early De natura boni to his last work, the Summa theologiae.[28]

Matter and form

Albert believed that all natural things were composed of composition of matter and form, he referred to it as quod est and quo est. Albert also believed that God alone is the absolute ruling entity. Albert's version of hylomorphism is very similar to the Aristotelian doctrine, but he also took some concepts from Avicenna.[29] Liber phisicorum sive auditus phisici is an eight-book commentary, which Albert wrote in France before 1349, on Aristotle’s Physics.[30]

Music

Albert is known for his commentary on the musical practice of his times. Most of his written musical observations are found in his commentary on Aristotle's Poetics. He rejected the idea of "music of the spheres" as ridiculous: movement of astronomical bodies, he supposed, is incapable of generating sound. He wrote extensively on proportions in music, and on the three different subjective levels on which plainchant could work on the human soul: purging of the impure; illumination leading to contemplation; and nourishing perfection through contemplation. Of particular interest to 20th-century music theorists is the attention he paid to silence as an integral part of music.

Metaphysics of morals

Both of his early treatises, De natura boni and De bono, start with a metaphysical investigation into the concepts of the good in general and the physical good. Albert refers to the physical good as bonum naturae. Albert does this before directly dealing with the moral concepts of metaphysics. In Albert's later works, he says in order to understand human or moral goodness, the individual must first recognize what it means to be good and do good deeds. This procedure reflects Albert's preoccupations with neo-Platonic theories of good as well as the doctrines of Pseudo-Dionysius.[31] Albert's view was highly valued by the Catholic Church and his peers.

Natural law

Albert devoted the last tractatus of De Bono to a theory of justice and natural law. Albert places God as the pinnacle of justice and natural law. God legislates and divine authority is supreme. Up until his time, it was the only work specifically devoted to natural law written by a theologian or philosopher.[32]

Friendship

Albert mentions friendship in his work, De bono, as well as presenting his ideals and morals of friendship in the very beginning of Tractatus II. Later in his life he published Super Ethica.[33] With his development of friendship throughout his work it is evident that friendship ideals and morals took relevance as his life went on. Albert comments on Aristotle's view of friendship with a quote from Cicero, who writes, "friendship is nothing other than the harmony between things divine and human, with goodwill and love". Albert agrees with this commentary but he also adds in harmony or agreement.[34] Albert calls this harmony, consensio, itself a certain kind of movement within the human spirit. Albert fully agrees with Aristotle in the sense that friendship is a virtue. Albert relates the inherent metaphysical contentedness between friendship and moral goodness. Albert describes several levels of goodness; the useful (utile), the pleasurable (delectabile) and the authentic or unqualified good (honestum). Then in turn there are three levels of friendship based on each of those levels. Friendship based on usefulness (amicitia utilis), friendship based on pleasure (amicitia delectabilis), and friendship rooted in unqualified goodness (amicitia honesti; amicitia quae fundatur super honestum).[35]

Cultural references

The iconography of the tympanum and archivolts of the late 13th-century portal of Strasbourg Cathedral was inspired by Albert's writings.[36] Albert is recorded as having made a mechanical automaton in the form of a brass head that would answer questions put to it. Such a feat was also attributed to Roger Bacon.[37]

Albert is frequently mentioned by Dante, who made his doctrine of free will the basis of his ethical system. In his Divine Comedy, Dante places Albertus with his pupil Thomas Aquinas among the great lovers of wisdom (Spiriti Sapienti) in the Heaven of the Sun. Albert is also mentioned, along with Agrippa and Paracelsus, in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, in which his writings influence a young Victor Frankenstein.

In The Concept of Anxiety, Søren Kierkegaard wrote that Albert, "arrogantly boasted of his speculation before the deity and suddenly became stupid." Kierkegaard cites Gotthard Oswald Marbach whom he quotes as saying "Albertus repente ex asino factus philosophus et ex philosopho asinus" [Albert was suddenly transformed from an ass into a philosopher and from a philosopher into an ass].[38]

In Walter M. Miller, Jr.'s post-apocalyptic novel A Canticle for Leibowitz there is an order of monks devoted to saving knowledge named the Albertian Order of Leibowitz in reference to Albert.

Influence and tribute

A number of schools have been named after Albert, including Albertus Magnus High School in Bardonia, New York;[39] Albertus Magnus Lyceum in River Forest, Illinois; and Albertus Magnus College in New Haven, Connecticut.[40]

Albertus Magnus Science Hall at Thomas Aquinas College, in Santa Paula, California, is named in honor of Albert. The main science buildings at Providence College and Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, are also named after him.

The central square at the campus of the University of Cologne features a statue of Albert and is named after him.

The Academy for Science and Design in New Hampshire honored Albert by naming one of its four houses Magnus House.

As a tribute to the scholar's contributions to the law, the University of Houston Law Center displays a statue of Albert. It is located on the campus of the University of Houston.

The Albertus-Magnus-Gymnasium is found in Regensburg, Germany.

In Managua, Nicaragua, the Albertus Magnus International Institute, a business and economic development research center, was founded in 2004.

In The Philippines, the Albertus Magnus Building at the University of Santo Tomas that houses the Conservatory of Music, College of Tourism and Hospitality Management, College of Education, and UST Education High School is named in his honor. The Saint Albert the Great Science Academy in San Carlos City, Pangasinan, which offers preschool, elementary and high school education, takes pride in having St. Albert as their patron saint. Its main building was named Albertus Magnus Hall in 2008. San Alberto Magno Academy in Tubao , La Union is also dedicated in his honor. This century-old Catholic high school continues to live on its vision-mission up to this day, offering Senior High school courses. Due to his contributions to natural philosophy, the plant species Alberta magna and the asteroid 20006 Albertus Magnus were named after him.

Numerous Catholic elementary and secondary schools are named for him, including schools in Toronto; Calgary; Cologne; and Dayton, Ohio.

The Albertus typeface is named after him.

At the University of Notre Dame du Lac in South Bend, Indiana, USA, the Zahm House Chapel is dedicated to St. Albert the Great. Fr. John Zahm, C.S.C., after whom the men's residence hall is named, looked to St. Albert's example of using religion to illumine scientific discovery. Fr. Zahm's work with the Bible and evolution is sometimes seen as a continuation of St. Albert's legacy.

Bibliography

Translations

- On the Causes of the Properties of the Elements, translated by Irven M. Resnick, (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2010) [translation of Liber de causis proprietatum elementorum]

- Questions concerning Aristotle's on Animals, translated by Irven M Resnick and Kenneth F Kitchell, Jr, (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2008) [translation of Quaestiones super De animalibus]

- The Cardinal Virtues: Aquinas, Albert, and Philip the Chancellor, translated by RE Houser, (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2004) [contains translations of Parisian Summa, part six: On the good and Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, book 3, dist. 33 & 36]

- The Commentary of Albertus Magnus on Book 1 of Euclid's Elements of Geometry, edited by Anthony Lo Bello, (Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2003) [translation of Priumus Euclidis cum commento Alberti]

- On Animals: A Medieval Summa Zoologica, translated by Kenneth F Kitchell, Jr. and Irven Michael Resnick, (Baltimore; London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999) [translation of De animalibus]

- Paola Zambelli, The Speculum Astronomiae and Its Enigma: Astrology, Theology, and Science in Albertus Magnus and His Contemporaries, (Dordrecht; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1992) [includes Latin text and English translation of Speculum astronomiae]

- Albert & Thomas: Selected Writings, translated by Simon Tugwell, Classics of Western Spirituality, (New York: Paulist Press, (1988) [contains translation of Super Dionysii Mysticam theologiam]

- On Union with God, translated by a Benedictine of Princethorpe Priory, (London: Burns Oates & Washbourne, 1911) [reprinted as (Felinfach: Llanerch Enterprises, 1991) and (London: Continuum, 2000)] [translation of De adherendo Deo]

See also

- Brazen Head

- Christian mysticism

- Incorruptibles

- List of Catholic saints

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- River Forest Thomism

- Science in the Middle Ages

References

- ↑ Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (ed.). A History of the University in Europe: Volume 1, Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 439.

- ↑ Irven Resnick (ed.), A Companion to Albert the Great: Theology, Philosophy, and the Sciences, BRILL, 2012, p. 4; Thomas F. Glick, Steven Livesey, Faith Wallis (eds.), Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 2014, p. 15; Pope Benedict XVI, Great Christian Thinkers: From the Early Church Through the Middle Ages, Fortress Press, 2011, p. 281.

- ↑ Latin: Albertus Teutonicus, Albertus Coloniensis.

- ↑ Weisheipl, James A. (1980), "The Life and Works of St. Albert the Great", in Weisheipl, James A., Albertus Magnus and the Sciences: Commemorative Essays, Studies and texts, 49, Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, p. 46, ISBN 0-88844-049-9

- ↑ Joachim R. Söder, "Albert der Grosse – ein staunen- erregendes Wunder," Wort und Antwort 41 (2000): 145; J.A. Weisheipl, "Albertus Magnus," Joseph Strayer ed., Dictionary of the Middle Ages 1 (New York: Scribner, 1982) 129.

- 1 2 Tugwell, Simon. Albert and Thomas, New York Paulist Press, 1988, p. 3, 96–7

- ↑ Tugwell, p. 4-5.

- 1 2 Kovach, Francs, and Rober Shahan. Albert the Great: Commemorative Essays . Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980, p.X

- ↑ Hampden, The Life, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kennedy, Daniel. "St. Albertus Magnus." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 10 Sept. 2014

- ↑ Histoire literaire de la France: XIIIe siècle. 19. p. 103. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- ↑ Probably Florentius de Hidinio, a.k.a. Florentius Gallicus, Histoire literaire de la France: XIIIe siècle, Volume 19, p. 104, Accessed October 27, 2012

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, Volume 10, p. 701. Accessed 9 June 2011

- ↑ Weisheipl O.P., J. A., "The Place of Study In the Ideal of St. Dominic", 1960. Accessed 19 March 2013

- 1 2 3 Führer, Markus, "Albert the Great", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.),

- ↑ "Zeittafel". Gemeinden.erzbistum-koeln.de. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ Carroll Cruz, Joan (1977). The Incorruptibles: A Study of the Incorruption of the Bodies of Various Catholic Saints and Beati. Charlotte, NC: TAN Books. ISBN 0-89555-066-0.

- ↑ An Smets, "Le réception en langue vulgaire du "De falconibus" d'Albert le Grand," in: Medieval Forms of Argument: Disputation and Debate, ed. Georgiana Donavin, Carol Poster, and Richard Utz (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2002), pp. 189–99.

- ↑ Katz, David A., "An Illustrated History of Alchemy and Early Chemistry", 1978

- ↑ Georg Wieland, "Albert der Grosse. Der Entwurf einer eigenständigen Philosophie," Philosophen des Mittelalters (Darmstadt: Primus, 2000) 124-39.

- ↑ Walsh, John, The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries. 1907:46 (available online).

- ↑ Emsley, John (2001). Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 43,513,529. ISBN 0-19-850341-5.

- ↑ Davidson, Michael W.; National High Magnetic Field Laboratory at The Florida State University (2003-08-01). "Molecular Expressions: Science, Optics and You — Timeline — Albertus Magnus". The Florida State University. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ↑ Szabadváry, Ferenc (1992). History of analytical chemistry. Taylor & Francis. p. 17. ISBN 2-88124-569-2.

- ↑ Julian Franklyn and Frederick E. Budd. A Survey of the Occult. Electric Book Company. 2001. p. 28-30. ISBN 1-84327-087-0.

- ↑ Paola Zambelli, "The Speculum Astronomiae and its Enigma" Dordrecht.

- ↑ Scott E. Hendrix, How Albert the Great's Speculum Astronomiae Was Interpreted and Used by Four Centuries of Readers (Lewiston: 2010), 44-46.

- ↑ Hendrix, 195.

- ↑ Kovach, Francs, and Rober Shahan. Albert the Great: Commemorative Essays . Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980, p. 133-135

- ↑ Mullen, Dennis. "Manuscript Monday: LJS 234 – Commentary on Aristotle's Physics". Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ↑ Cunningham, Stanley. Reclaiming Moral Agency: The Moral Philosophy of Albert the Great. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University Of America Press, 2008 p. 93

- ↑ Cunningham, Stanley. Reclaiming Moral Agency: The Moral Philosophy of Albert the Great. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University Of America Press, 2008 p.207

- ↑ Cunningham, Stanley. Reclaiming Moral Agency: The Moral Philosophy of Albert the Great. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University Of America Press, 2008 p.242

- ↑ Cunningham, Stanley. Reclaiming Moral Agency: The Moral Philosophy of Albert the Great. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University Of America Press, 2008 p.243

- ↑ Cunningham, Stanley. Reclaiming Moral Agency: The Moral Philosophy of Albert the Great. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University Of America Press, 2008 p.244

- ↑ France: A Phaidon Cultural Guide, Phaidon Press, 1985, ISBN 0-7148-2353-8, p. 705

- ↑ Chambers, Ephraim (1728). "Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences". Digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- ↑ The Concept of Anxiety, Princeton University Press, 1980, ISBN 0-691-02011-6, pp. 150–151

- ↑ "Albertus Magnus High School". Albertusmagnus.net. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ "Albertus Magnus College". Albertus.edu. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

Sources

- Tugwell, Simon. Albert and Thomas, Paulist Press, New York, 1988

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "article name needed". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (first ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "article name needed". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (first ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

Further reading

- Collins, David J. "Albertus, Magnus or Magus?: Magic, Natural Philosophy, and Religious Reform in the Late Middle Ages." Renaissance Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2010): 1–44.

- Honnefelder, Ludger (ed.) Albertus Magnus and the Beginnings of the Medieval Reception of Aristotle in the Latin West. From Richardus Rufus to Franciscus de Mayronis, (collection of essays in German and English), Münster : Aschendorff, 2005.

- Kovach,Francis J. & Shahan,Robert W. Albert the Great. Commemorative Essays, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

- Miteva, Evelina. "The Soul between Body and Immortality: The 13th Century Debate on the Definition of the Human Rational Soul as Form and Substance", in: Philosophia: E-Journal of Philosophy and Culture, 1/2012. ISSN 1314-5606.

- Resnick, Irven (ed.), A Companion to Albert the Great: Theology, Philosophy, and the Sciences, Leiden, Brill, 2013.

- Resnick, Irven e Kitchell Jr, Kenneth (eds.), Albert the Great: A Selective Annotated Bibliography, (1900-2000), Tempe, Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2004.

- Wallace, William A. (1970). "Albertus Magnus, Saint" (PDF). In Gillispie, Charles. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 1. New York: Scribner & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 99–103. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albertus Magnus. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Albert the Great |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Albertus Magnus |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Albertus Magnus. |

- Works by Albertus Magnus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Albertus Magnus at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Albert the Great at Internet Archive

- Works by Albertus Magnus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Führer, Markus. "Albert the Great". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Kennedy, D.J. (1913). "St. Albertus Magnus". Catholic Encyclopedia.

Kennedy, D.J. (1913). "St. Albertus Magnus". Catholic Encyclopedia.- Alberti Magni Works in Latin Online

- Albertus Magnus on Astrology & Magic

- "Albertus Magnus & Prognostication by the Stars"

- Albertus Magnus: "Secrets of the Virtues of Herbs, Stones and Certain Beasts" London, 1604, full online version.

- Albertus Magnus – De Adhaerendo Deo – On Cleaving to God

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by Albertus Magnus in .jpg and .tiff format.

- Albertus Magnus works at SOMNI in the collection of the Duke of Calabria.

- Alberti Magni De laudibus beate Mariae Virginis, Italian digitized codex of 1476 with a completed transcription of his work "Liber de laudibus gloriosissime Dei genitricis Marie"

- Albertus Magnus De mirabili scientia Dei, Italian digitized codex of 1484 with a transcription of the first part of his Summa Theologicae.