Habanero

| Habanero | |

|---|---|

| |

| Species | Capsicum chinense |

| Cultivar | 'Habanero' |

| Heat |

|

| Scoville scale | 100,000–350,000 SHU |

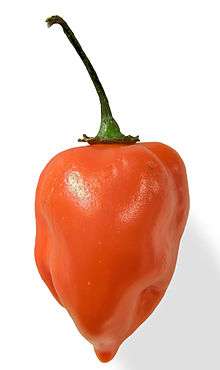

The habanero (/ˌhɑːbəˈnɛroʊ/; Spanish pronunciation: [aβaˈneɾo]) is a variety of chili pepper. Unripe habaneros are green, and they color as they mature. Common colors are orange and red, but white, brown, yellow, green, and purple are also seen.[1] Typically, a ripe habanero chili is 2–6 cm (0.8–2.4 in) long. Habanero chilis are very hot, rated 100,000–350,000 on the Scoville scale.[2] The habanero's heat, its flavor, and its floral aroma have made it a popular ingredient in hot sauces and spicy foods.

Name

The name indicates something or someone from La Habana (Havana). In English, it is sometimes spelled and pronounced habañero, the tilde being added as a hyperforeignism patterned after jalapeño.[3]

Origin and current use

The habanero chili comes from the Amazon region, from where it was spread, reaching Mexico.[4] A specimen of a domesticated habanero plant, dated at 8,500 years old, was found at an archaeological site in Peru. An intact fruit of a small domesticated habanero, found in pre-ceramic levels in Guitarrero Cave in the Peruvian highlands, was dated to 6500 BC.

The habanero chili was disseminated by the Spanish to other areas of the world, to the point that 18th-century taxonomists mistook China for its place of origin and called it Capsicum chinense ("the Chinese pepper").[5][6][7]

Today, the largest producer is Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula.[8] Habaneros are an integral part of Yucatecan food, accompanying most dishes, either in natural form or purée or salsa. Other modern producers include Belize, Panama, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, and parts of the United States, including Texas, Idaho, and California.

The Scotch bonnet is often compared to the habanero, since they are two varieties of the same species, but have different pod types. Both the Scotch bonnet and the habanero have thin, waxy flesh. They have a similar heat level and flavor. Although both varieties average around the same level of pungency, the actual degree varies greatly from one fruit to another with genetics, growing methods, climate, and plant stress.

In 1999, the habanero was listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world's hottest chili, but it has since been displaced by a number of other peppers. The bhut jolokia (or ghost pepper) and Trinidad moruga scorpion have since been identified as native Capsicum chinense subspecies even hotter than the habanero. Breeders constantly crossbreed subspecies to attempt to create cultivars that will break the record on the Scoville scale. One such example is the Carolina Reaper, a cross between a Bhut jolokia pepper with a particularly pungent red habanero.

Cultivation

Habaneros thrive in hot weather. As with all peppers, the habanero does well in an area with good morning sun and in soil with a pH level around 5 to 6 (slightly acidic). The habanero should be watered only when dry. Overly moist soil and roots will produce bitter-tasting peppers.

The habanero is a perennial flowering plant, meaning that with proper care and growing conditions, it can produce flowers (and thus fruit) for many years. Habanero bushes are good candidates for a container garden. In temperate climates, though, it is treated as an annual, dying each winter and being replaced the next spring. In tropical and subtropical regions, the habanero, like other chiles, will produce year round. As long as conditions are favorable, the plant will set fruit continuously.

Cultivars

Several growers have attempted to selectively breed habanero plants to produce hotter, heavier, and larger peppers. Most habaneros rate between 200,000 and 300,000 on the Scoville scale. In 2004, researchers in Texas created a mild version of the habanero, but retained the traditional aroma and flavor. The milder version was obtained by crossing the Yucatán habanero pepper with a heatless habanero from Bolivia over several generations.[9]

Black habanero is an alternative name often used to describe the dark brown variety of habanero chilis (although they are slightly different, being slightly smaller and slightly more sphere-shaped). Some seeds have been found which are thought to be over 7,000 years old. The black habanero has an exotic and unusual taste, and is hotter than a regular habanero with a rating between 400,000 and 450,000 Scoville units. Small slivers used in cooking can have a dramatic effect on the overall dish. Black habaneros take considerably longer to grow than other habanero chili varieties. In a dried form, they can be preserved for long periods of time, and can be reconstituted in water then added to sauce mixes. Previously known as habanero negro, or by their Nahuatl name, their name was translated into English by spice traders in the 19th century as "black habanero". The word "chocolate" was derived from the Nahuatl word, xocolātl [ʃoˈkolaːt͡ɬ], and was used in the description, as well (as "chocolate habanero"), but it proved to be unpronounceable to the British traders, so it was simply named "black habanero".[10]

A 'Caribbean Red', a cultivar within the habanero family, has a Scoville rating of 500,000.

Gallery

Red Habanero Chilis growing on the plant

Red Habanero Chilis growing on the plant- Habanero seedling

Habanero plant with fruit

Habanero plant with fruit.jpg) Habanero plant with fruit and flower

Habanero plant with fruit and flower- Orange habanero

Orange habaneros

Orange habaneros Red habaneros

Red habaneros Red habaneros on a plate, bought from a food store

Red habaneros on a plate, bought from a food store

See also

- Capsicum (pepper family)

- Jalapeño

- Scotch bonnet

References

- ↑ "Chili – Evergreen Orgnaics". evergreenorganicsbelize.com. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ↑ "Chile Pepper Heat Scoville Scale". Homecooking.about.com. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ↑ "Habanero". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ↑ "El chile habanero de Yucatán. Origen y dispersión prehispánica del chile habanero". Ciencia y Desarrollo. May 2006. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- ↑ Bosland, P.W. (1996). J. Janick, ed. "Capsicums: Innovative Uses of an Ancient Crop". Progress in New Crops. Arlington, VA: ASHS Press: 479–487. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ↑ "Bosland, "The History of the Chile Pepper"". Brooklyn Botanic Garden. Archived from the original on May 24, 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ Eshbaugh, W.H. 1993. History and exploitation of a serendipitous new crop discovery. pp. 132–139. In: J. Janick and J.E. Simon (eds.), New crops. Wiley, New York as reproduced at "Uncle Steve's Hot Stuff"

- ↑ "Profile of the Habanero Pepper". Whole Chile Pepper Magazine. July 1989. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ↑ Santa Ana III, Rod. "Texas Plant Breeder Develops Mild Habanero Pepper". AgNews, 12 August 2004.

- ↑ "Black Habanero".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- Aji Chombo peppers – photographic account of chilies grown in Fairfax, Virginia from seeds imported from Panama. Dale C. Clarke, 2003–04.