Doha

| Doha, Qatar الدوحة ad-Dawḥa | |

|---|---|

| City and Municipality | |

|

| |

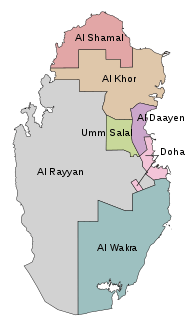

Location of the municipality of Doha within Qatar. | |

| Coordinates: 25°17′12″N 51°32′0″E / 25.28667°N 51.53333°ECoordinates: 25°17′12″N 51°32′0″E / 25.28667°N 51.53333°E | |

| Country |

|

| Municipality | Ad Dawhah |

| Established | 1825 |

| Area | |

| • City | 132 km2 (51 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • City | 1,351,000 |

| • Density | 10,000/km2 (27,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | N/A |

| Time zone | AST (UTC+3) |

Doha (Arabic: الدوحة, ad-Dawḥa or ad-Dōḥa; Arabic pronunciation: [addawħa] DAW-ha, literally in MSA: "the big tree", locally: "rounded bays")[2] is the capital city and most populous city of the State of Qatar. Doha has a population of 1,351,000 in a city proper with the population close to 1.5 million.[1] The city is located on the coast of the Persian Gulf in the east of the country. It is Qatar's fastest growing city, with over 50% of the nation's population living in Doha or its surrounding suburbs, and it is also the economic center of the country. It comprises one of the municipalities of Qatar.

Doha was founded in the 1820s as an offshoot of Al Bidda. It was officially declared as the country's capital in 1971, when Qatar gained independence.[3] As the commercial capital of Qatar and one of the emergent financial centers in the Middle East, Doha is considered a world city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network. Doha accommodates Education City, an area devoted to research and education.

The city was host to the first ministerial-level meeting of the Doha Development Round of World Trade Organization negotiations. It was also selected as host city of a number of sporting events, including the 2006 Asian Games, the 2011 Pan Arab Games and most of the games at the 2011 AFC Asian Cup. In December 2011, the World Petroleum Council held the 20th World Petroleum Conference in Doha.[4] Additionally, the city hosted the 2012 UNFCCC Climate Negotiations and is set to host a large number of the venues for the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

In May 2015, Doha was officially recognized as one of the New7Wonders Cities together with Vigan, La Paz, Durban, Havana, Beirut, and Kuala Lumpur.[5]

Etymology

The name "Doha" may have originated from the Arabic Ad-Dawḥa, "the big tree".[6] The reference might be to a prominent tree that stood at the site where the original fishing village arose, on the eastern coast of the Qatar peninsula. Alternatively, it may have been derived from "dohat" — Arabic for bay or gulf — referring to the Doha Bay area surrounding the Corniche.[2]

History

Establishment of Al Bidda

The city of Doha was formed after seceding from another local settlement known as Al Bidda. The earliest documented mention of Al Bidda was made in 1681, by the Carmelite Convent, in an account which chronicles several settlements in Qatar. In the record, the ruler and a fort in the confines of Al Bidda are alluded to.[7][8] Carsten Niebuhr, a European explorer who visited the Arabian Peninsula, created one of the first maps to depict the settlement in 1765 in which he labelled it as 'Guttur'.[7][9]

David Seaton, a British political resident in Muscat, wrote the first English record of Al Bidda in 1801. He refers to the town as 'Bedih' and describes the geography and defensive structures in the area.[10] He stated that the town had recently been settled by the Sudan tribe (Al-Suwaidi), whom he considered to be pirates. Seaton attempted to bombard the town with his warship, but returned to Muscat upon finding that the waters were too shallow to position his warship within striking distance.[11][12]

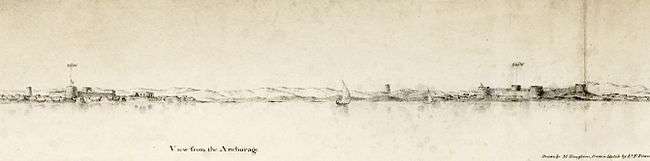

In 1820, British surveyor R.H. Colebrook, who visited Al Bidda, remarked on the recent depopulation of the town. He wrote:[11][13]

Guttur – Or Ul Budee [Al‐Bidda], once a considerable town, is protected by two square Ghurries [forts] near the sea shore; but containing no fresh water they are incapable of defence except against sudden incursions of Bedouins, another Ghurry is situated two miles inland and has fresh water with it. This could contain two hundred men. There are remaining at Ul Budee about 250 men, but the original inhabitants, who may be expected to return from Bahrein, will augment them to 900 or 1,000 men, and if the Doasir tribe, who frequent the place as divers, again settle in it, from 600 to 800 men.

The same year, an agreement known as the General Maritime Treaty was signed between the East India Company and the sheikhs of several Persian Gulf settlements (some of which were later known as the Trucial Coast). It acknowledged British authority in the Persian Gulf and sought to end piracy and the slave trade. Bahrain became a party to the treaty, and it was assumed that Qatar, perceived as a dependency of Bahrain by the British, was also a party to it.[14] Qatar, however, was not asked to fly the prescribed Trucial flag.[15] As punishment for alleged piracy committed by the inhabitants of Al Bidda and breach of treaty, an East India Company vessel bombarded the town in 1821. They razed the town, forcing between 300 and 400 natives to flee and temporarily take shelter on the islands between the Qatar and the Trucial Coast.[16]

Formation of Doha

Doha was founded in the vicinity of Al Bidda sometime during the 1820s.[17] In January 1823, political resident John MacLeod visited Al Bidda to meet with the ruler and initial founder of Doha, Buhur bin Jubrun, who was also the chief of the Al-Buainain tribe.[17][18] MacLeod noted that Al Bidda was the only substantial trading port in the peninsula during this time. Following the founding of Doha, written records often conflated Al Bidda and Doha due to the extremely close proximity of the two settlements.[17] Later that year, Lt. Guy and Lt. Brucks mapped and wrote a description of the two settlements. Despite being mapped as two separate entities, they were referred to under the collective name of Al Bidda in the written description.[19][20]

In 1828, Mohammed bin Khamis, a prominent member of the Al-Buainain tribe and successor of Buhur bin Jubrun as chief of Al Bidda, was embroiled in controversy. He had murdered a native of Bahrain, prompting the Al Khalifa sheikh to imprison him. In response, the Al-Buainain tribe revolted, provoking the Al Khalifa to destroy the tribe's fort and evict them to Fuwayrit and Ar Ru'ays. This incident allowed the Al Khalifa additional jurisdiction over the town.[21][22] With essentially no effective ruler, Al Bidda and Doha became a sanctuary for pirates and outlaws.[23]

In November 1839, an outlaw from Abu Dhabi named Ghuleta took refuge in Al Bidda, evoking a harsh response from the British. A.H. Nott, a British naval commander, demanded that Salemin bin Nasir Al-Suwaidi, chief of the Sudan tribe in Al Bidda, take Ghuleta into custody and warned him of consequences in the case of non-compliance. Al-Suwaidi obliged the British request in February 1840 and also arrested the pirate Jasim bin Jabir and his associates. Despite the compliance, the British demanded a fine of 300 German krones in compensation for the damages incurred by pirates off the coast of Al Bidda; namely for the piracies committed by bin Jabir. In February 1841, British naval squadrons arrived in Al Bidda and ordered Al-Suwaidi to meet the British demand, threatening consequences if he declined. Al-Suwaidi ultimately declined on the basis that he was uninvolved in bin Jabir's actions. On 26 February, the British fired on Al Bidda, striking a fort and several houses. Al-Suwaidi then paid the fine in full following threats of further action by the British.[23][24]

Isa bin Tarif, a powerful tribal chief from the Al Bin Ali tribe, moved to Doha in May 1843. He subsequently evicted the ruling Sudan tribe and installed the Al-Maadeed and Al-Kuwari tribes in positions of power.[25] Bin Tarif had been loyal to the Al Khalifa, however, shortly after the swearing in of a new ruler in Bahrain, bin Tarif grew increasingly suspicious of the ruling Al Khalifa and switched his allegiance to the deposed ruler of Bahrain, Abdullah bin Khalifa, whom he had previously assisted in deposing of. Bin Tarif died in the Battle of Fuwayrit against the ruling family of Bahrain in 1847.[25]

Arrival of Al Thani

The Al Thani migrated to Doha from Fuwayrit shortly after Bin Tarif's death in 1847 under the leadership of Mohammed bin Thani.[26][27] In the proceeding years, the Al Thani assumed control of the town. At various times, they swapped allegiances between the two prevailing powers in the area: the Al Khalifa and the Saudis.[26]

In 1867, a large number of ships and troops were sent from Bahrain to assault the towns Al Wakrah and Doha over a series of disputes. Abu Dhabi joined on Bahrain's behalf due to the conception that Al Wakrah served as a refuge for fugitives from Oman. Later that year, the combined forces sacked the two Qatari towns with around 2,700 men in what would come to be known as the Qatari–Bahraini War.[28][29] A British record later stated "that the towns of Doha and Wakrah were, at the end of 1867 temporarily blotted out of existence, the houses being dismantled and the inhabitants deported".[30]

The joint Bahraini-Abu Dhabi incursion and subsequent Qatari counterattack prompted the British political agent, Colonel Lewis Pelly, to impose a settlement in 1868. Pelly's mission to Bahrain and Qatar and the peace treaty that resulted were milestones in Qatar's history. It implicitly recognized the distinctness of Qatar from Bahrain and explicitly acknowledged the position of Mohammed bin Thani as an important representative of the peninsula's tribes.[31]

Shortly after the war, the Ottomans took up a rather nominal control of the country, constructing a base in Doha, with the acquiescence of Jassim Al Thani who wished to consolidate his control of the area. Prior to this, the town of Doha served as a stronghold for Bedouin fighters who resisted Ottoman rule.[32] By December 1871, Jassim Al Thani authorized the Ottomans to send 100 troops and equipment to Al Bidda.[33] Major Ömer Bey compiled a report on Al Bidda in January 1872, stating that it was an "administrative centre" with around 1,000 houses and 4,000 inhabitants.[34]

Disagreement over tribute and interference in internal affairs arose, eventually leading to the Battle of Al Wajbah in March 1893. Al Bidda fort served as the final point of retreat for Ottoman troops. While they were garrisoned in the fort, their corvette fired indiscriminately at the townspeople, killing a number of civilians.[35] The Ottomans eventually surrendered after Jassim Al Thani's troops cut off the town's water supply.[36] An Ottoman report compiled the same year reported that Al Bidda and Doha had a combined population of 6,000 inhabitants, jointly referring to both towns by the name of 'Katar'. Doha was classified as the eastern section of Katar.[34][37] The Ottomans held a passive role in Qatar's politics from the 1890s onward until fully relinquishing control during the beginning of the first World War.[14]

20th century

Pearling had come to play a pivotal commercial role in Doha by the 20th century. The population increased to around 12,000 inhabitants in the first half of the 20th century due to the flourishing pearl trade.[38] A British political resident noted that should the supply of pearls drop, Qatar would 'practically cease to exist'.[39] In 1907, the city accommodated 350 pearling boats with a combined crew size of 6,300 men. By this time, the average prices of pearls had more than doubled since 1877.[40] The pearl market collapsed that year, forcing Jassim Al Thani to sell the country's pearl harvest at half its value. The aftermath of the collapse resulted in the establishment of the country's first custom house in Doha.[39]

In April 1913, the Ottomans agreed to a British request that they withdraw all their troops from Qatar. Ottoman presence in the peninsula ceased, when in August 1915, the Ottoman fort in Al Bidda was evacuated shortly after the start of World War I.[41] One year later, Qatar agreed to be a British protectorate with Doha as its official capital.[42][43]

Buildings at the time were simple dwellings of one or two rooms, built from mud, stone and coral. Oil concessions in the 1920s and 1930s, and subsequent oil drilling in 1939, heralded the beginning of slow economic and social progress in the country. However, revenues were somewhat diminished due to the devaluation of pearl trade in the Persian Gulf brought on by introduction of the cultured pearl and the Great Depression.[44] The collapse of the pearl trade caused a significant population drop throughout the entire country.[38] It was not until the 1950s and 1960s that the country saw significant monetary returns from oil drilling.[14]

Qatar was not long in exploiting the new-found wealth from oil concessions, and slum areas were quickly razed to be replaced by more modern buildings. The first formal boys' schools was established in Doha in 1952, followed three years later by the establishment of a girls' school.[45] Historically, Doha had been a commercial port of local significance. However, the shallow water of the bay prevented bigger ships from entering the port until the 1970s, when its deep-water port was completed. Further changes followed with extensive land reclamation, which led to the development crescent-shaped bay.[46] From the 1950s to 1970s, the population of Doha grew from around 14,000 inhabitants to over 83,000, with foreign immigrants constituting about two-thirds of the overall population.[47]

Post-independence

Qatar officially declared its independence in 1971, with Doha as its capital city.[3] In 1973, the University of Qatar was opened by emiri decree,[48] and in 1975 the Qatar National Museum opened in what was originally the ruler's palace.[49] During the 1970s, all old neighborhoods in Doha were razed and the inhabitants moved to new suburban developments, such as Al Rayyan, Madinat Khalifa and Al Gharafa. The metropolitan area's population grew from 89,000 in the 1970s to over 434,000 in 1997. Additionally, land policies resulted in the total land area increasing to over 7,100 hectares by 1995, an increase from 130 hectares in the middle of the 20th century.[50]

In 1983, a hotel and conference center was developed at the north end of the Corniche. The 15-storey Sheraton hotel structure in this center would serve as the tallest structure in Doha until the 1990s.[50] In 1993, the Qatar Open became the first major sports event to be hosted in the city.[51] Two years later, Qatar stepped in to host the FIFA World Youth Championship, with all the matches being played in Doha-based stadiums.[52]

The Al Jazeera Arabic news channel began broadcasting from Doha in 1996.[53] In the late 1990s, the government planned the construction of Education City, a 2,500 hectare Doha-based complex mainly for educational institutes.[54] Since the start of the 21st century, Doha attained significant media attention due to the hosting of several global events and the inauguration of a number of architectural mega-projects.[55] One of the largest projects launched by the government was The Pearl-Qatar, an artificial island off the coast of West Bay, which launched its first district in 2004.[56] In 2006, Doha was selected to host the Asian Games, leading to the development of a 250-hectare sporting complex known as Aspire Zone.[51] During this time, new cultural attractions were constructed in the city, with older ones being restored. In 2006, the government launched a restoration program to preserve Souq Waqif's architectural and historical identity. Parts constructed after the 1950s were demolished whereas older structures were refurbished. The restoration was completed in 2008.[57] Katara Cultural Village was opened in the city in 2010 and has hosted the Doha Tribeca Film Festival since then.[58]

Geography

Doha is located on the central-east portion of Qatar, bordered by the Persian Gulf on its coast. It is bordered by Al Wakrah municipality to the south, Al Rayyan municipality to the west, Al Daayen municipality to the north and Umm Salal municipality to the northwest. Its elevation is 10 m (33 ft).[59] Doha is highly urbanized. Land reclamation off the coast has added 400 hectares of land and 30 km of coastline.[60] Half of the 22 km² of surface area which Hamad International Airport was constructed on was reclaimed land.[61] The geology of Doha is primarily composed of weathered unconformity on the top of the Eocene period Dammam Formation, forming dolomitic limestone.[62]

The Pearl is an artificial island in Doha with a surface area of nearly 400 ha (1,000 acres)[63] The total project has been estimated to cost $15 billion upon completion.[64] Other islands off Doha's coast include Palm Tree Island, Shrao's Island, Al Safia Island, and Alia Island.[65]

Climate

Doha has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). Summer is very long, from May to September, when its average high temperatures surpass 38 °C (100 °F) and often approach 45 °C (113 °F). Humidity is usually the lowest in May and June. Dewpoints can surpass 30 °C (86 °F) in the summer. Throughout the summer, the city averages almost no precipitation, and less than 20 mm (0.79 in) during other months.[66] Rainfall is scarce, at a total of 75 mm (2.95 in) per annum, falling on isolated days mostly between October to March. Winters are cool and the temperature rarely drops below 7 °C (45 °F).[67]

| Climate data for Doha (1962–2013, extremes 1962–2013) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.2 (88.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

46.0 (114.8) |

47.7 (117.9) |

49.0 (120.2) |

50.4 (122.7) |

48.3 (118.9) |

45.5 (113.9) |

43.4 (110.1) |

38.0 (100.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

50.4 (122.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

23.4 (74.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

32.5 (90.5) |

38.8 (101.8) |

41.6 (106.9) |

41.9 (107.4) |

40.9 (105.6) |

38.9 (102) |

35.4 (95.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

33.05 (91.49) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.5 (63.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

31.8 (89.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.8 (94.6) |

32.8 (91) |

29.5 (85.1) |

24.6 (76.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

26.1 (79) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30 (86) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

5.0 (41) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 13.2 (0.52) |

17.1 (0.673) |

16.1 (0.634) |

8.7 (0.343) |

3.6 (0.142) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

1.1 (0.043) |

3.3 (0.13) |

12.1 (0.476) |

75.2 (2.961) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 8.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 70 | 63 | 52 | 44 | 41 | 49 | 55 | 62 | 63 | 66 | 71 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 244.9 | 224.0 | 241.8 | 273.0 | 325.5 | 342.0 | 325.5 | 328.6 | 306.0 | 303.8 | 276.0 | 241.8 | 3,432.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.9 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 9.1 | 10.5 | 11.4 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 7.8 | 9.4 |

| Source #1: NOAA[67] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Qatar Meteorological Department (Climate Normals 1962–2013)[68] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20.5 °C (68.9 °F) | 19.1 °C (66.4 °F) | 20.9 °C (69.6 °F) | 23.7 °C (74.7 °F) | 28.2 °C (82.8 °F) | 30.9 °C (87.6 °F) | 32.8 °C (91.0 °F) | 33.9 °C (93.0 °F) | 33.1 °C (91.6 °F) | 31.0 °C (87.8 °F) | 27.4 °C (81.3 °F) | 23.1 °C (73.6 °F) |

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1820[11] | 250 | — |

| 1893[34] | 6,000 | +2300.0% |

| 1970[70] | 80,000 | +1233.3% |

| 1986[3] | 217,294 | +171.6% |

| 2001[71] | 299,300 | +37.7% |

| 2004[3] | 339,847 | +13.5% |

| 2005[72][73] | 400,051 | +17.7% |

| 2010[74] | 796,947 | +99.2% |

| c-census; e-estimate | ||

A significant portion of Qatar's population resides within the confines of Doha and its metropolitan area.[75] The district with the highest population density is the central area of Al Najada, which also accommodates the highest total population in the country. The population density across the greater Doha region ranges from 20,000 people per km² to 25 people per km².[76]

The following table is the total population of the wider Doha metropolitan area.[77]

| Year | Metro population |

|---|---|

| 1997 | 434,000[50] |

| 2004 | 644,000[78] |

| 2008 | 998,651[79] |

The following table is a breakdown of registered live births by nationality and sex for Doha. Places of birth are based on the home municipality of the mother at birth.[77][80]

| Registered live births by nationality and sex | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Qatari | Non-Qatari | Total | ||||||

| M | F | Total | M | F | Total | M | F | Total | |

| 2001 | 1,045 | 1,035 | 2,080 | 1,878 | 1,741 | 3,619 | 2,923 | 2,776 | 5,699 |

| 2002 | 932 | 943 | 1,875 | 1,877 | 1,780 | 3,657 | 2,809 | 2,723 | 5,532 |

| 2003 | 1,104 | 1,068 | 2,172 | 2,064 | 1,963 | 4,027 | 3,168 | 3,031 | 6,199 |

| 2004 | 1,054 | 1,000 | 2,054 | 1,946 | 1,814 | 3,760 | 3,000 | 2,814 | 5,814 |

| 2005 | 867 | 900 | 1,767 | 2,007 | 1,892 | 3,899 | 2,874 | 2,792 | 5,666 |

| 2006 | 961 | 947 | 1,908 | 2,108 | 2,008 | 4,116 | 3,069 | 2,955 | 6,024 |

| 2007 | 995 | 918 | 1,913 | 2,416 | 2,292 | 4,708 | 3,411 | 3,210 | 6,621 |

| 2008 | 955 | 895 | 1,850 | 2,660 | 2,623 | 5,283 | 3,615 | 3,518 | 7,133 |

| 2009 | 1,098 | 1,043 | 2,141 | 3,025 | 2,954 | 5,979 | 4,123 | 3,997 | 8,120 |

| 2010[81] | 840 | 831 | 1,671 | 3,079 | 2,840 | 5,919 | 3,919 | 3,671 | 7,590 |

| 2011[82] | 926 | 933 | 1,859 | 3,400 | 3,180 | 6,580 | 4,326 | 4,113 | 8,439 |

Ethnicity and languages

The population of Doha is overwhelmingly composed of expatriates, with Qatari nationals forming a minority. The largest portion of expatriates in Qatar are from South-East and South Asian countries, mainly India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Philippines, and Bangladesh with large numbers of expatriates also coming from the Levant Arab countries, North Africa, and East Asia. Doha is also home to a large number of expatriates from Europe, North America, South Africa, and Australia.[83]

Arabic is the official language of Qatar. English is commonly used as a second language,[84] and a rising lingua franca, especially in commerce.[85] As there is a large expatriate population in Doha, languages such as Malayalam, Tagalog, Spanish, French, Urdu and Hindi are widely spoken.[83]

In 2004, the Foreign Ownership of Real Estate Law was passed, permitting non-Qatari citizens to buy land in designated areas of Doha, including the West Bay Lagoon, the Qatar Pearl, and the new Lusail City.[55] Prior to this, expatriates were prohibited from owning land in Qatar. Ownership by foreigners in Qatar entitles them to a renewable residency permit, which allows them to live and work in Qatar.[75]

Each month, thousands immigrate to Qatar, and as a result, Doha has witnessed explosive growth rates in population. Doha's population currently stands at around one million,[79] with the population of the city more than doubling from 2000 to 2010. Due to the high influx of expatriates, the Qatari housing market saw a shortage of supply which led to a rise in prices and increased inflation. The gap in the housing market between supply and demand has narrowed, however, and property prices have fallen in some areas following a period which saw rents triple in some areas.[86]

According to Qatar Chamber, expatriate workers have remitted $60bn between 2006 and 2012. 54 percent of the workers' remittances of $60bn were routed to Asian countries, followed by Arab nations that accounted for nearly half that volume (28 percent). India was the top destination of the remittances, followed by the Philippines, while the US, Egypt and the neighbouring UAE trailed.[87]

Religion

The majority of residents in Doha are Muslim.[88] Catholics account for over 90% of the 150,000 Christian population in Doha.[89] Following decrees by the Emir for the allocation of land to churches, the first Catholic church, Our Lady of the Rosary, was opened in Doha in March 2008. The church structure is discreet and Christian symbols are not displayed on the outside of the building.[90] Several other churches exist in Doha, including the Syro-Malabar Church, Malankara Orthodox Church, Mar Thoma Church (affiliated with the Anglicans, but not part of the Communion), CSI Church, Syro-Malankara Church and a Pentecostal church. A majority of mosques are either Muwahhid or Sunni-oriented.[91]

Administration

According to the Ministry of Municipality and Urban Planning,[92] the Municipality of Qatar became the first municipality to be established in 1963. Later that year, name was changed to Municipality of Doha. The country has been divided into seven municipalities since 2006.[93] Doha is the most populated municipality among them with a population of 796,947 as of 2010.[94]

Districts

At the turn of the 20th century, Doha was divided into 9 main districts.[95] In the 2010 census, there were more than 60 districts recorded in Doha Municipality.[94] Some of the districts of Doha include:

- Al Bidda (البدع)

- Al Dafna (الدفنة)

- Al Ghanim (الغانم)

- Al Markhiya (المرخية)

- Al Sadd (السد)

- Al Waab (الوعب)

- Bin Mahmoud (فريج بن محمود)

- Madinat Khalifa (مدينة خليفة)

- Musheireb (مشيرب)

- Najma (نجمه)

- Old Airport (المطار القديم)

- Qutaifiya (القطيفية)

- Ras Abu Aboud (راس أبو عبود)

- Rumeilah (الرميلة)

- Umm Ghuwailina (ام غو يلينه)

- West Bay (الخليج الغربي)

Shortly after Qatar gained independence, many of the districts of old Doha including Al Najada, Al Asmakh and Old Al Hitmi faced gradual decline and as a result much of their historical architecture has been demolished.[96] Instead, the government shifted their focus toward the Doha Bay area, which housed districts such as Al Dafna and West Bay.[96]

Economy

.jpg)

Doha is the economic centre of Qatar. The city is the headquarters of numerous domestic and international organizations, including the country's largest oil and gas companies, Qatar Petroleum, Qatargas and RasGas. Doha's economy is built primarily on the revenue the country has made from its oil and natural gas industries.[97]

Beginning in the late 20th century, the government launched numerous initiatives to diversify the country's economy in order to decrease its dependence on oil and gas resources. Doha International Airport was constructed in a bid to solidify the city's diversification into the tourism industry.[97] This was replaced by Hamad International Airport in 2014. The new airport is almost twice the size of the former and features two of the longest runways in the world.[98]

As a result of Doha's rapid population boom and increased housing demands, real estate prices have raised significantly.[99] Real estate prices experienced a further spike after Qatar won the rights to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[100] Al Asmakh, a Qatari real estate firm, released a report in 2014 which revealed substantial increases in real estate prices following a peak in 2008. Prices increased 5 to 10% in the first quarter of 2014 from the end of 2013.[99][101] A 2015 study conducted by Numbeo, a crowd-sourced database, named Doha as the 10th most expensive city to live in globally.[102] This rate of growth has led to the development of planned communities in and around the city.[103]

Thirty-nine new hotels were under construction in 2011.[104] Doha was included in Fortune's 15 best new cities for business in 2011.[105]

Infrastructure

Architecture

Most traditional architecture in the Old Doha districts have been demolished to make space for new buildings.[96] As a result, a number of schemes have been taken to preserve the city's cultural and architectural heritage, such as the Qatar Museums Authority's 'Al Turath al Hai' ('living heritage') initiative.[106] Katara Cultural Village is a small village in Doha launched by sheikh Tamim Al Thani to preserve the cultural identity of the country.[107]

In 2011, more than 50 towers were under construction in Doha,[104] the largest of which was the Doha Convention Center Tower.[108] Constructions were suspended in 2012 following concerns that the tower would impede flight traffic.[109]

In 2014, Abdullah Al Attiyah, a senior government official, announced that Qatar would be spending $65bn on new infrastructure projects in upcoming years in preparation for the 2022 World Cup as well as progressing towards its objectives set out in the Qatar National Vision 2030.[110]

Atmosphere

Due to excessive heat from the sun during the summer, some Doha-based building companies have attempted various forms of cooling technology to alleviate the extremely torrid climatic conditions. This comes in cheaper forms such as through improvisation of optical phenomena such as shadows and more expensive forms such as ventilation, coolants, refrigerants, cryogenics and dehumidifiers.[111] Discussions regarding temperature control have also been features of various scheduled events involving large crowds.[112] There are other initiatives that attempt to counter the heat by increasing the traditional office opening times, other standard white collar workday hours, retail operations late into the evening and weather alteration methods such as cloud seeding.[113][114] Others include utilizing whiter and brighter construction materials to increase the albedo effects.[115] Nonetheless, despite these measures, Doha and other Qatari environs could become uninhabitable for humans due to the climate change bringing about extreme heat by the year 2071.[116]

Planned communities

One of the largest projects underway in Qatar is Lusail City, a planned community north of Doha which is estimated to be completed by 2020 at a cost of approximately $45bn. It is designed to accommodate 450,000 people.[117] Al Waab City, another planned community under development, is estimated to cost QR15 bn.[118] In addition to housing 8,000 individuals, it will also have shopping malls, educational, and medical facilities.[118]

Transportation

Since 2004, Doha has been undergoing a huge expansion to its transportation network, including the addition of new highways, the opening of a new airport in 2014, and the currently ongoing construction of an 85 km metro system. This has all been as a result of Doha's massive growth in a short period of time, which has resulted in congestion on its roads. The first phase of the metro system is expected to be operational by 2019.[119]

In 2015, the Public Works Authority declared their plan to construct a free-flowing road directly linking Al-Wakrah and Mesaieed to Doha in order to decrease traffic congestion in the city. It is set for completion by 2018.[120]

Education

Doha is the educational center of the country and contains the highest preponderance of schools and colleges.[70] In 1952, the first formal boys' school was opened in Doha. This was proceeded by the opening of the first formal girls' school three years later.[121] The first university in the state, Qatar University, was opened in 1973.[122] It provided separate faculties for both men and women.[123]

Education City, a 14 km2 education complex launched by non-profit organization Qatar Foundation, began construction in 2000.[124] It houses eight universities, the country's top high school, and offices for Al Jazeera's children television channel.[124]

In 2009, the government launched the World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE), a global forum that brings together education stakeholders, opinion leaders and decision makers from all over the world to discuss educational issues.[125] The first edition was held in Doha in November 2009.[126]

Some of the universities in Doha include:

- Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar

- Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar

- Hamad Bin Khalifa University

- Cornell University[127]

- Harvard University[127]

- Yale University[127]

- HEC Paris

- Northwestern University in Qatar

- Texas A&M University at Qatar

- UCL Qatar[128]

- Virginia Commonwealth University

- Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar

- CHN University

- College of the North Atlantic

- Qatar University

- Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies

- University of Calgary

At their respective Doha campuses, Harvard and Yale teach Sharia law.[127]

In the United States, a number of retired government officials sent a letter to Harvard expressing their opposition to Harvard's teaching of Shariah law in Qatar. Retired U.S. Major General Paul Vallely, who had once served as Deputy Commander for the United States Pacific Command, was among the letter's signers.[127]

Sports

Football

Football is the most popular sport in Doha. There are seven Doha-based sports clubs with football teams currently competing in the Qatar Stars League, the country's top football league. They are Al Ahli, Al Arabi, Al Sadd, Al Sailiya, El Jaish, Lekhwiya and Qatar SC.[129] Al Sadd, Al Arabi and Qatar SC are the three most successful teams in the league's history.[130]

Numerous football tournaments have been hosted in Doha. The most prestigious tournaments include the 1988 and 2011 editions of the AFC Asian Cup[131] and the 1995 FIFA World Youth Championship.[52]

In December 2010, Qatar won the rights to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[132] Three of the nine newly announced stadiums will be constructed in Doha, including Sports City Stadium, Doha Port Stadium, and Qatar University Stadium. Additionally, the Khalifa International Stadium is set to undergo an expansion.[133]

Basketball

Doha was the host of the official 2005 FIBA Asia Championship, where Qatar's national basketball team finished 3rd, its best performance to date, and subsequently qualified for the Basketball World Cup.[134]

Other sports

In 2001, Qatar became the first country in the Middle East to hold a women's tennis tournament: Qatar holds both the Qatar Open for Women and the ladies ITF (International Tennis Federation) tournament. Since 2008, the Sony Ericsson Championships (equivalent to the ATP's season-ending Championships) has taken place in Doha, in the Khalifa International Tennis Complex, and features record prize money of $4.45 million, including a check of $1,485,000 for the winner, which represents the largest single guaranteed payout in women's tennis.[135]).

.jpg)

Doha hosted the 15th Asian Games, held in December 2006, spending a total of $2.8 billion for its preparation.[136] The city also hosted the 3rd West Asian Games in December 2005.[137] Doha was expected to host the 2011 Asian Indoor Games; but the Qatar Olympic Committee cancelled the event.[138]

The city submitted a bid for the 2016 Olympics.[139] On June 4, 2008, the city was eliminated from the shortlist for the 2016 Olympic Games. On August 26, 2011 it was confirmed that Doha would bid for the 2020 Summer Olympics.[140] Doha however failed to become a Candidate City for the 2020 Games.[141]

The MotoGP motorcycling grand prix of Doha is held annually at Losail International Circuit, located just outside the city boundaries.[142] The city is also the location of the Grand Prix of Qatar for the F1 Powerboat World Championship, annually hosting a round in Doha Bay.[143] Beginning in November 2009, Doha has been host of the The Oryx Cup World Championship, a hydroplane boat race in the H1 Unlimited season. The races take place in Doha Bay.[144]

In April 2012 Doha was awarded the 2014 FINA World Swimming Championships [145] and the 2012 World Squash Championships.[146]

Stadiums and sport complexes

Aspire Academy was launched in 2004 with the aim of creating world-class athletes. It is situated in the Doha Sports City Complex, which also accommodates the Khalifa International Stadium, the Hamad Aquatic Centre, the Aspire Tower and the Aspire Dome. The latter has hosted more than 50 sporting events since its inception, including some events during the 2006 Asian Games.[147]

Sporting venues in Doha and its suburbs include:

- Hamad bin Khalifa Stadium – Al-Ahli Stadium

- Jassim Bin Hamad Stadium (Al Sadd Stadium)

- Al-Arabi Stadium – Grand Hamad Stadium

- Hamad Aquatic Centre

- Khalifa International Stadium – Main venue for the 2006 Asian Games.

- Khalifa International Tennis and Squash Complex

- Qatar Sports Club Stadium

Culture

Doha was chosen as the Arab Capital of Culture in 2010.[148] Cultural weeks organized by the Ministry of Culture, which featured both Arab and non-Arab cultures, were held in Doha from April to June to celebrate the city's selection.[149]

Arts

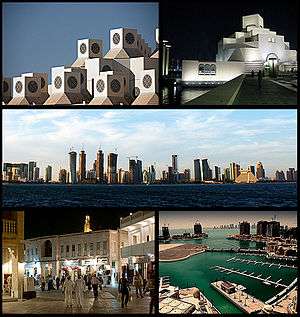

The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, opened in 2008, is regarded as one of the best museums in the region.[150] This, and several other Qatari museums located in the city, like the Arab Museum of Modern Art, falls under the Qatar Museums Authority (QMA) which is led by Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, the daughter of the emir of Qatar.[151]

Media

Qatar's first radio station, Mosque Radio, began broadcasting in the 1960s from Doha.[152] The multinational media conglomerate Al Jazeera Media Network is based in Doha with its wide variety of channels of which Al Jazeera Arabic, Al Jazeera English, Al Jazeera Documentary Channel, Al Jazeera Mubasher, beIN Sports Arabia and other operations are based in the TV Roundabout in the city.[153] Al-Kass Sports Channel's headquarters is also located in Doha.[154]

Film

The Doha Film Institute (DFI) is an organisation established in 2010 to oversee film initiatives and create a sustainable film industry in Qatar. DFI was founded by H.E. Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani.[155]

The Doha Tribeca Film Festival (DTFF), partnered with the American-based Tribeca Film Festival, was held annually in Doha from 2009 to 2012.[156]

Attractions

- Aladdin's Kingdom

Twin towns and sister cities

Gallery

Click on the thumbnail to enlarge.

-

Souq Waqif, Doha

-

Doha Marina, shot in 2007.

-

The Emiri Diwan, Al Bidda.

-

Post-modern buildings in Doha

-

Doha City Center Mall.

-

The old and new zones of Doha are clearly visible from the International Space Station.

-

Msheireb Enrichment Centre moored off Doha Corniche.

-

Aspire Park, Al Waab.

-

Doha skyline from the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

-

Doha, Qatar. Skyline at night. Showing the expansion of the business district.

-

Al Bidda Park

-

Aerial view of Doha

See also

- Doha Declaration

- Doha Development Round of World Trade Organization (WTO) talks

- Qatar National Day which is held in Doha every year on December 18

References

- 1 2 "Doha municipality accounts for 40% of Qatar population". Gulf Times. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- 1 2 Fahmy, Heba (4 April 2015). "What's in a name? The meanings of Qatar districts, explained". Doha News. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Encyclopædia Britannica. "Doha – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "Welcome to the 20th World Petroleum Congress". 20wpc.com. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ Tejada, Ariel Paolo (9 May 2015). "Vigan declared 'Wonder City'". Manila: The Philippine STAR. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ Graham, Helga (1978). Arabian time machine: self-portrait of an oil state. William Heinemann Ltd. p. 26. ISBN 978-0434303502.

The word Doha itself is said to mean 'the place of the big tree', as eloquent a comment as any on the sparsity of the vegetation in Qatar, indeed throughout the Persian Gulf generally, in former times.

- 1 2 "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 1. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Billecocq, Xavier Beguin (2003). Le Qatar et les Français: cinq siècles de récits de voyage et de textes d'érudition. Collection Relations Internationales & Culture. ISBN 9782915273007.

- ↑ Rahman, Habibur (2006). The Emergence Of Qatar. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0710312136.

- ↑ Carter, Robert. "Origins of Doha Season 1 Archive Report". academia.edu. p. 11. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 2. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Al-Qasimi, Sultan Mohammed (1995). The journals of David Seton in the Gulf 1800-1809. Exeter University Press.

- ↑ H. Rahman (2006), p. 36.

- 1 2 3 Toth, Anthony. "Qatar: Historical Background." A Country Study: Qatar (Helen Chapin Metz, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (January 1993). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 3. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [793] (948/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 4. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ H. Rahman (2006), p. 63.

- ↑ "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 5. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Brucks, G.B. (1985). Memoir descriptive of the Navigation of the Gulf of Persia in R.H. Thomas (ed) Selections from the records of the Bombay Government No XXIV (1829). New York: Oleander press.

- ↑ Zahlan, Rosemarie Said (1979). The creation of Qatar (print ed.). Barnes & Noble Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0064979658.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [794] (949/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ H. Rahman (2006), pp. 90–92.

- 1 2 "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 6. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 7. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "Line of succession: The Al Thani rule in Qatar". Gulf News. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "'A collection of treaties, engagements and sanads relating to India and neighbouring countries [...] Vol XI containing the treaties, & c., relating to Aden and the south western coast of Arabia, the Arab principalities in the Persian Gulf, Muscat (Oman), Baluchistan and the North-West Frontier Province' [113v] (235/822)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ "'File 19/243 IV Zubarah' [8r] (15/322)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [801] (956/1782)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ H. Rahman (2006), p. 123.

- ↑ H. Rahman (2006), pp. 138–139.

- ↑ H. Rahman (2006), p. 140.

- 1 2 3 Kurşun, Zekeriya (2002). The Ottomans in Qatar : a history of Anglo-Ottoman conflicts in the Persian Gulf. Istanbul : Isis Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9789754282139.

- ↑ Zahlan, Rosemarie Said (1979). The creation of Qatar (print ed.). Barnes & Noble Books. p. 53. ISBN 978-0064979658.

- ↑ H. Rahman (2006), p. 152.

- ↑ "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 11. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- 1 2 Florian Wiedmann, Ashraf M. Salama, Alain Thierstein. "Urban evolution of the city of Doha: an investigation into the impact of economic transformations on urban structures" (PDF). p. 38. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- 1 2 Althani, Mohamed (2013). Jassim the Leader: Founder of Qatar. Profile Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-1781250709.

- ↑ Casey, Paula; Vine, Peter (1991). The heritage of Qatar (print ed.). Immel Publishing. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0907151500.

- ↑ M. Althani (2013), p, 134.

- ↑ H. Rahman (2006), p. 291.

- ↑ "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 16. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "Pearl Diving in Qatar". USA Today. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ Abu Saud, Abeer (1984). Qatari Women: Past and Present. Longman Group. p. 173. ISBN 978-0582783720.

- ↑ "Qatar in perspective: an orientation guide" (PDF). Defense League Institute Foreign Language Center. 2010. p. 8.

- ↑ Florian Wiedmann, Ashraf M. Salama, Alain Thierstein. "Urban evolution of the city of Doha: an investigation into the impact of economic transformations on urban structures" (PDF). p. 41. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "Our history". Qatar University. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "Qatar's National Museum eyeing 2016 opening". Doha News. 6 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Florian Wiedmann, Ashraf M. Salama, Alain Thierstein. "Urban evolution of the city of Doha: an investigation into the impact of economic transformations on urban structures" (PDF). pp. 44–45. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- 1 2 Florian Wiedmann, Ashraf M. Salama, Alain Thierstein. "Urban evolution of the city of Doha: an investigation into the impact of economic transformations on urban structures" (PDF). p. 47. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- 1 2 "FIFA World Youth Championship Qatar 1995 - matches". FIFA. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "AL JAZEERA TV: The History of the Controversial Middle East News Station Arabic News Satellite Channel History of the Controversial Station". Allied-media. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ Florian Wiedmann, Ashraf M. Salama, Alain Thierstein. "Urban evolution of the city of Doha: an investigation into the impact of economic transformations on urban structures" (PDF). p. 49. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- 1 2 Wiedmann, Florian; Salama, Ashraf M (2013). Demystifying Doha: On Architecture and Urbanism in an Emerging City. Ashgate. ISBN 9781409466345.

- ↑ Khalil Hanware (21 March 2005). "Pearl-Qatar Towers Lure International Investors". Jeddah: Arab News. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Exell, Karen; Rico, Trinidad (2014). Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula: Debates, Discourses and Practices. Ashgate. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-4094-7009-0.

- ↑ Elspeth Black. "Katara: The Cultural Village". The Culture Trip. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "Map of Doha, Qatar". Climatemps.com. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "New land by the sea: Economically and socially, land reclamation pays" (PDF). International Association of Dredging Companies. p. 4. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "DEME: Doha Airport Built on Reclaimed Land Becomes Fully Operational". Dredging Today. 3 June 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Ed Blinkhorn (April 2015). "Geophysical GPR Survey" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Ron Gluckman (May 2008). "Artificial Islands: In Dubai, a world, and universe of new real estate". Gluckman. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "Say Hello To Pearl Qatar – The World's Most Luxurious Artificial Island". Wonderful Engineering. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "Qatar islands". Online Qatar. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "Doha weather information". Wunderground.com. 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- 1 2 "Doha International Airport Climate Normals 1962-1992". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Climate Information For Doha". Qatar Meteorological Department. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Monthly Doha water temperature chart". Seatemperatures.org. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- 1 2 Abdulla Juma Kobaisi. "The Development of Education in Qatar, 1950–1970" (PDF). Durham University. p. 11. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ "Doha". Tiscali.co.uk. 1984-02-21. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "Sheraton Doha Hotel & Resort | Hotel discount bookings in Qatar". Hotelrentalgroup.com. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "hotelsdoha.eu". hotelsdoha.eu. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Qatar population statistics". geohive.com. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- 1 2 Marco Dilenge. "Dubai and Doha: Unparalleled Expansion" (PDF). Crown Records Management UK. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "Facts and figures". lusail.com. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Population statistics". Qatar Information Exchange. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. 2006. p. 61.

- 1 2 "Doha 2016 Summer Olympic Games Bid". Gamesbids.com. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "WELCOME TO Qatar Statistics Authority WEBSITE :". Qsa.gov.qa. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Births and deaths in 2010" (PDF). Qatar Information Exchange. Qatar Statistics Authority. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ "Births and deaths in 2011" (PDF). Qatar Information Exchange. Qatar Statistics Authority. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- 1 2 Humaira Tasnim, Abhay Valiyaveettil, Dr. Ingmar Weber, Venkata Kiran Garimella. "Socio-geographic map of Doha". Qatar Computing Research Institute. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Baker, Colin; Jones, Sylvia Prys (1998). Encyclopedia of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education. Multilingual Matters. p. 429. ISBN 978-1853593628.

- ↑ Guttenplan, D. D. (11 June 2012). "Battling to Preserve Arabic From English's Onslaught". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Breaking News, UAE, GCC, Middle East, World News and Headlines - Emirates 24/7". Business24-7.ae. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Expatriates Remit $60bn in 7 years".

- ↑ "Religious demography of Qatar" (PDF). US Department of State. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Shabina Khatri (20 June 2008). "Qatar opens first church, quietly". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Sonia Verma (14 March 2008). "Qatar hosts its first Christian church". The Times. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Oman Economic and Development Strategy Handbook, International Business Publications, USA - 2009, page 40

- ↑ "وزارة البلدية والتخطيط العمراني". Baladiya.gov.qa. 2013-01-04. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Qatar Municipalities". Qatar Ministry of Municipality and Urban Planning. Archived from the original on 2011-12-22.

- 1 2 "Census 2010". Qatar Statistics Authority. 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ Jaidah, Ibrahim; Bourennane, Malika (2010). The History of Qatari Architecture 1800-1950. Skira. p. 25. ISBN 978-8861307933.

- 1 2 3 Djamel Bouassa. "Al Asmakh historic district in Doha, Qatar: from an urban slum to living heritage". academia.edu. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- 1 2 Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (2006). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 138. ISBN 978-1576079195.

- ↑ Marco Rinaldi (5 May 2014). "Hamad International Airport by Hok". aasarchitecture.com. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- 1 2 Peter Kovessy (23 June 2014). "Reports: Housing supply not keeping up with population rise". Doha News. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Rohan Soman (13 May 2013). "Real estate prices in Qatar skyrocket". BQ Doha. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Qatar Real Estate Report Q1 2014" (PDF). Al Asmakh Real Estate Firm. 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Neha Batia (5 July 2015). "Doha city rents are world's tenth most expensive". Construction Week Online. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Falling oil prices and real estate markets". BQ Doha. 10 March 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- 1 2 Bullivant, Lucy (2012). Masterplanning Futures. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-0415554473.

- ↑ Dawsey, Josh. "Global 500 2011: 15 best new cities for business - FORTUNE on CNNMoney". Money.cnn.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "The Winners of the Old Doha Prize Competition Announced". Marhaba. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "About us". Katara. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ "The World's Tallest Buildings". Bloomberg. 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Flight concerns stop 550m Doha tower development". Construction Week Online. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Doha rolling out the dough for Qatar infrastructure, set to launch new projects worth $65 billion". Al Bawaba. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ Air Conditioning: A Practical Introduction - Page 106, David V. Chadderton - 2014

- ↑ The Report: Qatar 2012 - Page 187, Oxford Business Group

- ↑ Red Sea and the Persian Gulf - Page 237, 2007

- ↑ Sixth Conference on Planned and Inadvertent Weather Modification, p 307, 1977

- ↑ Hegazy, Ahmed (2016). Plant Ecology in the Middle East. p. 205.

- ↑ https://www.inverse.com/article/7472-qatar-could-become-too-hot-for-humans-just-50-years-after-the-2022-world-cup

- ↑ Tony Manfred (22 September 2014). "Qatar Is Building A $45 Billion City From Scratch For The World Cup That It Might Lose". Business Insider. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Al Waab City Phase 1 Opens". Qatar Today Online. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ William Skidmore (24 October 2012). "Qatar's key infrastructure projects". Construction Week Online. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ "Ashghal unveils QR10bn projects for Mesaieed and Al Wakra". The Peninsula Qatar. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ Abu Saud, Abeer (1984). Qatari Women: Past and Present. Longman Group. p. 173. ISBN 978-0582783720.

- ↑ "Qatar University". Qatar e-government. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ Abu Saud (1973), p. 173

- 1 2 Simeon Kerr (20 October 2013). "Doha's Education City is a boost for locals". Financial Times. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ "World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE) 2014". UNESCO. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "The 2009 World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE) convened November 16-18, in Doha, Qatar under the theme "Global Education: Working Together for Sustainable Achievements"". WISE Qatar. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "While U.S. universities see dollar signs in Qatari partnerships, some cry foul". Gulf News Journal. 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ↑ UCL Qatar

- ↑ "Qatar Stars League 2014/2015 » Teams". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "Qatar Stars League » Champions". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "AFC Asian Cup history". AFC Asian Cup. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cup Hosts Announced". BBC News. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "2022 FIFA World Cup Bid Evaluation Report: Qatar" (PDF). FIFA. 2010-12-05.

- ↑ 2005 FIBA Asia Championship, ARCHIVE.FIBA.com, Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ ""Season to End in Doha 2008–2010" on the Sony Ericsson WTA Tour website". Sonyericssonwtatour.com. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ Patrick Dixon. "The Future Of Qatar - Rapid Growth". globalchange.com. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "Doha 2005: 3rd West Asian Games". Olympic Council of Asia. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "Qatar Participates in 4th Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games This Week". Marhaba. 30 June 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "Information on 2016 Olympic Games Bids". Gamesbids.com. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "Doha to bid for 2020 Olympics". Espn.go.com. 2011-08-26. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ "IOC selects three cities as Candidates for the 2020 Olympic Games". Olympic.org. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ "About the circuit". MotoGP. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "Power boats". Oryx in-flight magazine. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "2014 Oryx Cup Dates Announced". H1 Unlimited. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "Doha awarded 2014 World Short Course Swimming Championships". Insidethegames.biz. 2012-04-04. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ "Doha picked to host 2012 World Squash Championships". Insidethegames.biz. 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ "The Aspire Dome, centre stage for Doha 2010". IAAF Athletics. 3 November 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "Irina Bokova receives the Prize 'Doha 2010 Arab Capital of Culture'". UNESCO. 17 December 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ "Doha, 2010 Arab culture capital, to host Arab and non-Arab cultural weeks". Habib Toumi. 4 April 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ "Art in Qatar: A Smithsonian in the sand". The Economist. 1 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ "QMA Board of Trustees". Qatar Museums Authority. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ Gunter, Barrie; Dickinson, Roger (2013). News Media in the Arab World: A Study of 10 Arab and Muslim Countries. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 31. ISBN 978-1441174666.

- ↑ "Company Overview of Al Jazeera Media Network". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ↑ "Al Kass Selects BFE as Integrator". finance.yahoo.com. Marketwired. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ↑ "Article in Variety Arabia". Tradearabia.com. 2010-05-16. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ "Whatever happened to the Qatari film industry?". theguardian.com. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ↑ "Sister cities". eBeijing. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Doha. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Doha. |

Doha travel guide from Wikivoyage

Doha travel guide from Wikivoyage- Projects in Doha and Major Construction and Architectural Developments

- Information and History of Doha