Acedia

Acedia (/əˈsiːdiə/; also accidie or accedie /ˈæksᵻdi/, from Latin acedĭa, and this from Greek ἀκηδία, "negligence") is a state of listlessness or torpor, of not caring or not being concerned with one's position or condition in the world. It can lead to a state of being unable to perform one's duties in life. Its spiritual overtones make it related to but arguably distinct from depression.[1] Acedia was originally noted as a problem among monks and other ascetics who maintained a solitary life.

Aquinas' definition

The Oxford Concise Dictionary of the Christian Church[2] defines acedia (or accidie) as "a state of restlessness and inability either to work or to pray". Some see it as the precursor to sloth—one of the seven deadly sins. In his sustained analysis of the vice in Q. 35 of the Second Part (Secunda Secundae) of his Summa Theologica, the 13th-century theologian Thomas Aquinas identifies acedia with "the sorrow of the world" (compare Weltschmerz) that "worketh death" and contrasts it with that sorrow "according to God" described by St. Paul in 2 Cor. 7:10. For Aquinas, acedia is "sorrow about spiritual good in as much as it is a Divine good." It becomes a mortal sin when reason consents to man's "flight" (fuga) from the Divine good, "on account of the flesh utterly prevailing over the spirit."[3] Acedia is essentially a flight from the divine that leads to not caring even that one does not care. The ultimate expression of this is a despair that ends in suicide.

Aquinas's teaching on acedia in Q. 35 contrasts with his prior teaching on charity's gifted "spiritual joy," to which acedia is directly opposed, and which he explores in Q. 28 of the Secunda Secundae. As Aquinas says, "One opposite is known through the other, as darkness through light. Hence also what evil is must be known from the nature of good."[4]

Ancient depictions

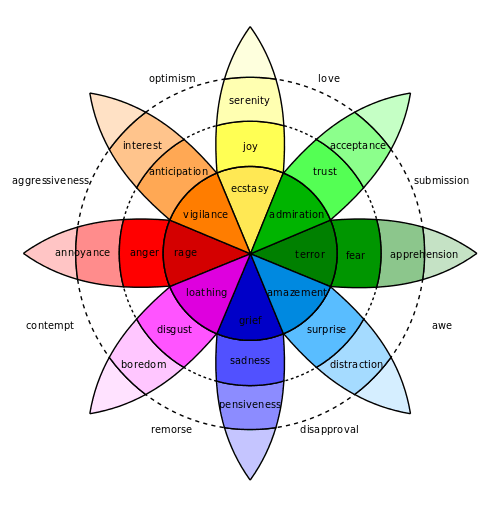

Moral theologians, intellectual historians and cultural critics have variously construed acedia as the ancient depiction of a variety of psychological states, behaviors or existential conditions: primarily laziness, apathy, ennui or boredom.

The demon of acedia holds an important place in early monastic demonology and proto-psychology. In the late fourth century Evagrius of Pontus, for example, characterizes it as "the most troublesome of all" of the eight genera of evil thoughts. As with those who followed him, Evagrius sees acedia as a temptation, and the great danger lies in giving in to it. Evagrius' contemporary, the Desert Father John Cassian, depicted the apathetic restlessness of acedia, "the noonday demon", in the coenobitic monk:

He looks about anxiously this way and that, and sighs that none of the brethren come to see him, and often goes in and out of his cell, and frequently gazes up at the sun, as if it was too slow in setting, and so a kind of unreasonable confusion of mind takes possession of him like some foul darkness.[5]

Foul darkness is the natural setting of Satan: in the medieval Latin tradition of the seven deadly sins, acedia has generally been folded into the sin of sloth. The Benedictine Rule directed that a monk displaying the outward signs of acedia

"should be reproved a first and a second time. If he does not amend he must be subjected to the punishment of the rule so that the others may have fear.[6]

Signs

Acedia is indicated by a range of signs. These signs (or symptoms) are typically divided into two basic categories: somatic and psychological. Acedia frequently presents signs somatically. Such bodily symptoms range from mere sleepiness to general sickness or debility, along with a host of more specific symptoms: weakness in the knees, pain in the limbs, and fever. An anecdote attributed to the Desert Mother Amma Theodora[7] also connects somatic pain and illness with the onset of acedia. A host of psychological symptoms can also signify the presence of acedia, which affects the mental state and behavior of the afflicted. Some commonly reported psychological signs revolve around a lack of attention to daily tasks and an overall dissatisfaction with life. The best-known of the psychological signs of acedia is tedium, boredom or general laziness. Author Kathleen Norris in her book Acedia and Me asserts that dictionary definitions such as torpor and sloth fail to do justice to this "temptation"; she believes a state of restlessness, of not living in the present and seeing the future as overwhelming is more accurate a definition than straight laziness: it is especially present in monasteries, due to the cutting off of distractions, but can invade any vocation where the labor is long, the rewards slow to appear, such as scientific research, long term marriages etc. Another sign is a lack of caring, of being unfeeling about things, whether that be your appearance, hygiene, your relationships, your community's welfare, the world's welfare etc.; all of this, Norris relates, is connected to the hopelessness and vague unease that arises from having too many choices, lacking true commitment, of being "a slave from within". She relates this to forgetfulness about "the one thing needful": remembrance of God. Anthony Robbins, the well known life coach, also believes a lack of commitment to spiritual growth will lead to negative states of mind.

Anecdotally, in Tsarist Russia, if a wealthy noble woman came down with long-term depression (which can overlap with acedia) allegedly a trusted antidote was to put her in an old peasant woman's house and make her do many of the basic household duties such as fetching the water, sweeping the floor, chopping wood etc. Basic manual tasks were also considered vital to keep spirits up in the Desert Father tradition of early Christian monasticism.

In culture

- Acedia plays an important role in the literary criticism of Walter Benjamin. In his study of baroque literature, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, Benjamin describes acedia as a moral failing, an "indolence of the heart" that ruins great men. Benjamin considers acedia to be a key feature of many baroque tragic heroes, from the minor dramatic figures of German tragedy to Shakespeare's Hamlet: "The indecisiveness of the prince, in particular, is nothing other than saturnine acedia." It is this slothful inability to make decisions that leads baroque tragic heroes to passively accept their fate, rather than resisting it in the heroic manner of classical tragedy.[8]

- Roger Fry saw acedia or gloominess as a twentieth century peril to be fought by a mixture of work and of determined pleasure in life.[9]

- Chekhov and Samuel Becket's plays often have themes of acedia.

- Aldous Huxley wrote an essay on acedia called "Accidie". A non-Christian, he examines "the noon day demons" original delineation by the Desert Fathers, and concludes that it is one of the main diseases of the modern age.

- The story appearing in several music videos by the rock group Red featured an evil company called the "Accedia Corporation" that fosters passivity and mindless compliance. (Videos: "Feed the Machine", "Release the Panic", "Perfect Life", "Darkest Part")

See also

- Aboulia (disorder of diminished motivation)

- Anomie

- Identity crisis

- Joie de vivre

- Sloth (deadly sin)

- Weltschmerz

References

- ↑ the hermitary and Meng-hu (2004). "Acedia, Bane of Solitaries". Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 22 Dec 2008.

- ↑ "accidie" The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Ed. E. A. Livingstone. Oxford University Press, 2006. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 1 November 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t95.e35>

- ↑ Summa, II-II, 35, 3.

- ↑ Summa, I, 48, 1.

- ↑ John Cassian, The Institutes, (Boniface Ramsey, tr.) 2000:10:2, quoted in Stephen Greenblatt, The Swerve: how the world became modern, 2011:26.

- ↑ ut ceteri timeant: The Rule of Benedict 48:19-20, quoted in Greenblatt 2011:26: "The symptoms of psychic pain would be driven out by physical pain".

- ↑ Laura Swan (2001). The Forgotten Desert Mothers: Sayings, Lives, and Stories of Early Christian Women. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4016-9.

- ↑ Walter Benjamín; John Osborne (2003). The origin of German tragic drama. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-413-7. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ↑ H. Lee, Virginia Wolff (1996) p. 708

External links

- "Struggling with a 'bad thought'" by Kathleen Norris, Special to CNN, 6 April 2010

- Spiritual Apathy: The Forgotten Deadly Sin by Abbot Christopher Jamison

- The sin of sloth or the illness of the demons? – The demon of acedia in early Christian monasticism, Andrew Crislip, Harvard Theological Review, 1 April 2005, published by the Cambridge University Press

- Acedia, Tristitia and Sloth: Early Christian Forerunners to Chronic Ennui

- Falling Out of Love: Akedia (acedia) and spiritual apathy