Accademia della Crusca

| |

|

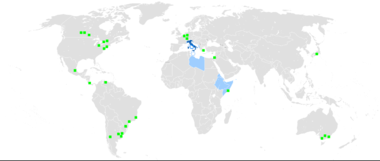

The geographic distribution of the Italian language in the world. | |

| Abbreviation | La Crusca |

|---|---|

| Motto |

Il più bel fior ne coglie (She gathers the fairest flower) |

| Formation | 1583 |

| Headquarters | Florence, Italy |

Official language | Italian |

President | Claudio Marazzini |

| Website |

accademiadellacrusca |

| Part of a series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

The Accademia della Crusca [akkaˈdɛːmja ˈdella ˈkruska] (Academy of the bran), generally abbreviated as La Crusca, is an Italian society for scholars and Italian linguists and philologists established in Florence. It is the most important research institution on Italian language[1] as well as the oldest linguistic academy in the world.[2]

The Accademia was founded in Florence in 1583 and, until 1900, it has been characterized by its efforts to maintain the purity of the Italian language.[3] Crusca means "bran" in Italian, which conveys the metaphor that its work is similar to winnowing as it is well explained by the emblem of the Accademia della Crusca that depicts a sifter that is straining out corrupt words and structures (as wheat is separated from bran). The academy motto is "Il più bel fior ne coglie" ('She gathers the fairest flower'), a famous verse of the Italians poet Francesco Petrarca. In 1612, the Accademia published the first edition of its Dictionary: the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca,[4] which also served as the model for similar works in French, Spanish, German and English.[1]

The academy is a member of the European Federation of National Linguistic Institutes,[5] a body convened to develop a joint policy to protect the integrity of national languages. The Federation has two Italian members: the Accademia della Crusca and the Opera del Vocabolario Italiano del CNR (an initiative launched by the Centro Nazionale delle Ricerche with the collaboration of the Accademia della Crusca).[6]

Origins

The founders were originally called the brigata dei Crusconi and constituted a kind of circle, where the members included poets, men of letters, and lawyers. The members usually assembled on pleasant and convivial occasions, during which cruscate—discourses in a merry and playful style, which have neither a beginning nor an end—were recited for the purposes of fun. The declared intention of the group was to create a distance between itself and the pedantry of the Accademia Fiorentina, protected by Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici, and to contrast itself with the severe and classicising style of that body. The Crusconi battled against the classical pedantry of the Accademia through the use of humour, satire, and irony. However, it was important that this battle was fought without compromising the primary intention of the group, which was typically literary, and expounded in high quality literary disputes.

The founders of the Accademia della Crusca are traditionally identified as: Giovanni Battista Deti (‘Sollo’), Anton Francesco Grazzini (‘Lasca’), Bernardo Canigiani (‘Gramolato’), Bernardo Zanchini (‘Macerato’), Bastiano de’ Rossi (‘Inferigno’); they were joined in October 1582 by Lionardo Salviati[7] ('Infarinato') (1540–1589). Under his forceful leadership, and based on his defining contributions, at the beginning of 1583, the Accademia took on a new form, directing itself definitively to the end that the academicians now identified: to demonstrate and to conserve the beauty of the Florentine vulgar tongue, modelled upon the authors of the Trecento.[8]

Monosini and the first Vocabolario

One of the earliest scholars to influence the work of the Crusca was Agnolo Monosini. He contributed greatly to the 1612 edition of Vocabolario della lingua italiana, especially with regard[9] to the Greek Etymology, which, he maintained, made a significant contribution to the Fiorentine idiom of the period.[10][4]

The Accademia thus abandoned the jocular character of its earlier meetings in order to take up the normative role it would assume from then on. The very title of the Accademia came to be interpreted in a new way: the academicians of the Crusca would now work to distinguish the good and pure part of the language (the farina, or whole wheat) from the bad and impure part (the crusca, or bran). From this is derived the symbolism of the Crusca: its logo shows a frullone or sifter [11][12] with the Petrarchan motto Il più bel fior ne coglie (She gathers the fairest flower).[8] The members of the Accademia were given nicknames associated with corn and flour, and seats in the form of breadbaskets with backs in the shape of bread shovel were used for their meetings.[13][14]

Beccaria and Verri opposition

The linguistic purism of the Accademia found opposition in Cesare Beccaria and the Verri brothers (Pietro and Alessandro), who through their journal Il Caffè systematically attacked the Accademia's archaisms as pedantic, denouncing the Accademia while invoking for contrast no less than the likes of Galileo and Newton and even modern intellectual cosmopolitanism itself.[15]

Baroque Period

The Accademia's activities carried on with both high- and low- points until 1783, when Pietro Leopoldo quit and, with several other academicians, created the second Accademia Fiorentina. In 1808, however, the third Accademia Fiorentina was founded and, by a decree of 19 January 1811, signed by Napoleon, the Crusca was re-established with its own status of autonomy, statutes and previous aims.[16][3]

In the 20th century, the decree of 11 March 1923 changed its composition and its purpose. The compilation of the Vocabolario, hitherto the duty of the Crusca, was removed from it and passed to a private society of scholars; the Crusca was entrusted with the compilation of philological texts. In 1955, however, Bruno Migliorini and others began discussion of the return of the work of preparing the Vocabolario to the Crusca.[17]

Composition

Current members

- Maria Luisa Altieri Biagi, Bologna

- Paola Barocchi, Florence

- Gian Luigi Beccaria, Turin

- Pietro Beltrami, Pisa

- Francesco Bruni, Venice

- Vittorio Coletti, Genoa

- Rosario Coluccia, Lecce

- Maurizio Dardano, Rome

- Tullio De Mauro, Rome

- Massimo Fanfani, secretary, Florence

- Piero Fiorelli, Florence

- Lino Leonardi, Florence

- Giulio Lepschy, Reading

- Paola Manni, vice president, Florence

- Nicoletta Maraschio, Florence

- Claudio Marazzini, president, Turin

- Aldo Menichetti, Fribourg

- Carlo Alberto Mastrelli, Florence

- Sergio Mattarella, honoris causa member, Palermo

- Pier Vincenzo Mengaldo, Padua

- Silvia Morgana, Milan

- Bice Mortara Garavelli, Turin

- Giorgio Napolitano, honoris causa member, Naples

- Teresa Poggi Salani, Florence

- Ornella Pollidori Castellani, Florence

- Lorenzo Renzi, Padua

- Francesco Sabatini, Rome

- Cesare Segre, Milan

- Luca Serianni, Rome

- Angelo Stella, Pavia

- Alfredo Stussi, Pisa

- Alberto Varvaro, Naples

- Ugo Vignuzzi, Rome

- Maurizio Vitale, Milan

Associates

- Luciano Agostiniani, Florence

- Gabriella Alfieri, Catania

- Ilaria Bonomi, Milan

- Michele Cortelazzo, Padua

- Paolo D'Achille, Rome

- Vittorio Formentin, Padua

- Giuseppe Frasso, Milan

- Rita Librandi, Naples

- Alberto Nocentini, Florence

- Alessandro Pancheri, Pescara

- Leonardo Maria Savoia, Florence

- Mirko Tavoni, Pisa

- Pietro Trifone, Rome

References

- 1 2 "The Accademia". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ Informazioni sulle origini from La Crusca website.

- 1 2 "The reopening of the Accademia (1811) and the fifth edition of the Vocabolario (1863–1923)". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- 1 2 "The first edition of the Vocabolario (1612)". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ "Partner List". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ "Recent history". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ "Infarinato". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Origins and foundation". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ See on-line manuscripts in Crusca Biblioteca Digitale

- ↑ However, Monosini's key work was the Floris Italicae lingue libri novem ("The Flower of Italian Language in a new book") published in 1604, in which he collected many vernacular Italian proverbs and Idioms, and compared and contrasted them with Greek and Latin.

- ↑ "Frullone: Traduzione in inglese di Frullone Dizionario inglese Corriere.it". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Sala delle Pale". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ "The second edition of the Vocabolario (1623)". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ "The third edition of the Vocabolario (1691)". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ Alberto Arbasino. "Genius Loci" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ↑ "The fourth edition of the Vocabolario (1729–1738) and the suppression of the Accademia (1783)". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Accademia today". Retrieved 4 August 2015.

Sources

- (Italian) Yates, Frances A. "The Italian Academies", in: Collected Essays; vol. II: Renaissance and Reform; the Italian Contribution, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1983 ISBN 0-7100-9530-9

- (English) Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. Early Modern Europe, 1450–1789. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006 ISBN 0-521-80894-4

External links

- The search for Some Historical References of Academy (Italian)

- Dictionary of Academy of Bran the online version of editions 1612 through 1923 (Italian)

- Academy of Bran English or Italian version (Italian)

- Academy of Bran and Some Historical References (Italian)

- Accademia Della Crusca Collection From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress