A Midsummer Night's Dream (opera)

| A Midsummer Night's Dream | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Benjamin Britten | |

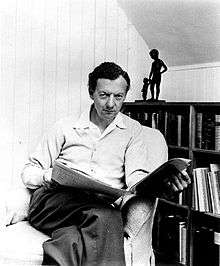

The composer in 1968 | |

| Librettist |

|

| Language | English |

| Based on | Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream |

| Premiere |

11 June 1960 Aldeburgh Festival |

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Op. 64, is an opera with music by Benjamin Britten and set to a libretto adapted by the composer and Peter Pears from William Shakespeare's play, A Midsummer Night's Dream. It was premiered on 11 June 1960 at the Aldeburgh Festival, conducted by the composer and with set and costume designs by Carl Toms.[1] Stylistically, the work is typical of Britten, with a highly individual sound-world – not strikingly dissonant or atonal,[1] but replete with subtly atmospheric harmonies and tone painting. The role of Oberon was composed for the countertenor Alfred Deller. Atypically for Britten, the opera did not include a leading role for his partner Pears, who instead was given the comic drag role of Flute/Thisbe.

Performance history

A Midsummer Night's Dream was first performed on 11 June 1960 at the Jubilee Hall, Aldeburgh, UK as part of the Aldeburgh Festival. Conducted by the composer, it was directed by the choreographer John Cranko.[2]

The opera has entered the general operatic repertory, and has become one of the most frequently performed operas written since the second world war.

Dream was performed at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 1961, produced by John Gielgud and conducted by Georg Solti. This production was revived six times to 1984.[3]

The English Music Theatre Company staged the opera at Snape Maltings in 1980, directed by Christopher Renshaw and designed by Robin Don; the production was revived at the Royal Opera House for one performance in 1986.[4]

In 2005, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, produced a version directed by Olivia Fuchs at the Linbury Studio Theatre with the Tiffin Boys' Choir. William Towers was Oberon, and Gillian Keith Tytania.[5]

English National Opera's production of 2011, directed by Christopher Alden, set the opera in a mid-20th-century school, with Oberon (Iestyn Davies) and Tytania (Anna Christy) as teachers and Puck and the fairies as schoolboys. Oberon's relationship with Puck (Jamie Manton) is given overtly sexual overtones, and Puck responds with alternate anger and despair to Oberon's new-found interest in Tytania's Changeling boy. The silent older man who stalks the action in the first two acts is revealed to be Theseus (Paul Whelan); reviewers have suggested that in this staging Theseus himself was once the object of Oberon's attentions, and is either watching history repeating itself, or is in fact daydreaming the magical events of the opera prior to his marriage to Hippolyta.[6][7]

Baz Luhrmann directed a music video of an arrangement of "Now Until the Break of Day" from the finale of act 3 for his 1998 album Something for Everybody featuring Christine Anu and David Hobson.

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 11 June 1960 (Conductor: Benjamin Britten Director: John Cranko) |

|---|---|---|

| Oberon, King of the Fairies | countertenor | Alfred Deller |

| Tytania, Queen of the Fairies | coloratura soprano | Jennifer Vyvyan |

| Puck | speaking role | Leonide Massine II |

| Cobweb | treble | Kevin Platts |

| Mustardseed | treble | Robert McCutcheon |

| Moth | treble | Barry Ferguson |

| Peaseblossom | treble | Michael Bauer |

| Lysander | tenor | George Maran |

| Demetrius | baritone | Thomas Hemsley |

| Hermia, in love with Lysander | mezzo-soprano | Marjorie Thomas |

| Helena, in love with Demetrius | soprano | April Cantelo |

| Theseus, Duke of Athens | bass | Forbes Robinson |

| Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons | contralto | Johanna Peters |

| Bottom, a weaver | bass baritone | Owen Brannigan |

| Quince, a carpenter | bass | Norman Lumsden |

| Flute, a bellows-mender | tenor | Peter Pears |

| Snug, a joiner | bass | David Kelly |

| Snout, a tinker | tenor | Edward Byles |

| Starveling, a tailor | baritone | Joseph Ward |

Instrumentation

- woodwinds: 2 flutes (2nd with piccolo), oboe (with English horn), 2 clarinets, bassoon

- Brass: 2 horns, trumpet in D, trombone

- percussion (2 players): timpani, triangle, cymbals, tambourine, gong, 2 wood blocks, vibraphone, glockenspiel, xylophone, tamburo, snare drum, tenor drum, bass drum, 2 bells

- Other: 2 harps, harpsichord (celesta), strings (minimum: 4.2.2.2.2)

- Stage band: sopranino recorders, cymbals, 2 wood blocks

Analysis

Britten delineated the three tiers of characters, the rustics being given folk-like "simple" music, the lovers a more romantic sound-world and the fairies being represented in a very ethereal way. Almost all of the action now takes place in the woods around Athens, and the fairies inhabit a much more prominent place in the drama. The comic performance by the rustics of Pyramus and Thisbe at the final wedding takes on an added dimension as a parody of nineteenth-century Italian opera. Thisbe's lament, accompanied by obbligato flute, is a parody of a Donizetti "mad scene".[1]

The opera contains several innovations: it is extremely rare in opera that the lead male role is written for the countertenor voice to sing. The part of Oberon was created by Alfred Deller. Britten wrote specifically for his voice, which, despite its ethereal quality, had a low range compared to more modern countertenors. Oberon's music almost never requires the countertenor to sing both at the top of the alto range and forte.

The plot of the opera follows that of the play, with several alterations. Most of Shakespeare's act 1 is cut, compensated for by the opera's only added line: "Compelling thee to marry with Demetrius." Therefore, much greater precedence is given to the wood, and to the fairies.[1] This is also indicated by the opening portamenti strings, and by the ethereal countertenor voice that is Oberon, the male lead, who throughout is accompanied by a characteristic texture of harp and celeste, in the same way that Puck's appearance is heralded by the combination of trumpet and snare-drum.[1]

The opera opens with a chorus, "Over hill, over dale" from Tytania's attendant fairies, played by boy sopranos. Other highlights include Oberon's florid – the exotic celeste is especially notable[1] – aria,"I know a bank" (inspired by Purcell's "Sweeter than roses", which Britten had previously arranged for Pears to sing[8] ), Tytania's equally florid "Come now, a roundel", the chorus's energetic "You spotted snakes", the hilarious comedy of Pyramus and Thisbe, and the final trio for Oberon, Tytania and the chorus.

The original play is an anomaly among Shakespeare's works, in that it is very little concerned with character, and very largely concerned with psychology. Britten follows this to a large extent, but subtly alters the psychological focus of the work. The introduction of a chorus of boy-fairies means that the opera becomes greatly concerned with the theme of purity. It is these juvenile fairies who eventually quell the libidinous activities of the quartet of lovers, as they sing a beautiful melody on the three "motto chords" (also on the four "magic" chords) of the second act:[1] "Jack shall have Jill/Naught shall go ill/The man shall have his mare again/And all shall be well." Sung by boys, it could be considered that this goes beyond irony, and represents an idealised vision of a paradise of innocence and purity that Britten seems to have been captivated by throughout his life.[8]

Britten also pays attention to the play's central motif: the madness of love. Curiously he took the one relationship in the play that is grotesque (that of Tytania and Bottom) and placed it in the centre of his opera (in the middle of act 2).[8] Women in Britten operas tend to run to extremes, being either predators or vulnerable prey, but Tytania is an amalgam; she dominates Bottom, but is herself completely dominated by Oberon and Puck, the couple that are usually considered to really hold power in The Dream.[8] Their cruel pranks eventually quell her coloratura, which until she is freed from the power of the love-juice is fiendishly difficult to sing.

Britten also parodied operatic convention in less obvious ways than Pyramus and Thisbe. Like many other operas, A Midsummer Night's Dream opens with a chorus, but it is a chorus of unbroken boys' voices, singing in unison. After this comes the entrance of the prima donna and the male lead, who is as far away as possible from Wagner's heldentenors, and as close as it is possible to get to Handel's castrati of the 18th century.:[1] "There is an air of baroque fantasy in the music." Britten's treatment of Puck also suggests parody.[8] In opera, the hero's assistant is traditionally sung by baritones, yet here we have an adolescent youth who speaks, rather than sings.

Britten thought the character of Puck "absolutely amoral and yet innocent."[9] Describing the speaking, tumbling Puck of the opera, Britten wrote "I got the idea of doing Puck like this in Stockholm, where I saw some Swedish child acrobats with extraordinary agility and powers of mimicry, and suddenly realised we could do Puck this way."[9]

The opera originally received a mixed critical assessment. Britten's estranged collaborator W. H. Auden dismissed it as "dreadful – pure Kensington,"[10] while many others praised it highly. It is fairly regularly performed.

Recordings

There are many recordings available, including two conducted by the composer, one a live recording of the June 11 1960 premiere with the complete original cast, the second a studio recording made in 1967 with some of the original cast, Deller as Oberon, Owen Brannigan as Bottom, and Peter Pears elevated from Flute to Lysander, which omits some music from the lovers' awakening early in act 3. [11]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Whittall (2008), pp. 379–381

- ↑ "Britten, Benjamin A Midsummer Night's Dream (1960)". Boosey & Hawkes. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ "A Midsummer Night's Dream (1961)". Royal Opera House Collections Online. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ "A Midsummer Night's Dream (1986)". Royal Opera House Collections Online. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ "A Midsummer Night's Dream (2005)". Royal Opera House Collections Online. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ Clements, Andrew (20 May 2011). "A Midsummer Night's Dream – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ↑ White, Michael. "ENO's shocking new paedophile Midsummer Night's Dream is brilliant, and I hated it". The Telegraph. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brett, Philip (1990). Britten's Dream (Brief essay to accompany the Britten recording). Decca Records.

- 1 2 Britten, Benjamin (5 June 1960). "A New Britten Opera". The Observer.

- ↑ White, Michael (22 May 1994). "Sweet Dream, sour looks". The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ↑ Opera Discography: Recordings of A Midsummer Night's Dream on operadis-opera-discography, accessed 2 May 2011

Cited sources

- Whittall, Arnold, (1998) "Midsummer Night's Dream, A" in Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Vol. 3. London: MacMillan Publishers, Inc. 1998 ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ISBN 1-56159-228-5

Sources

- Holden, Amanda (ed.), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam, 2001. ISBN 0-14-029312-4

- Warrack, John and West, Ewan, The Oxford Dictionary of Opera New York: OUP: 1992 ISBN 0-19-869164-5

External links

- Synopsis of Britten's Midsummer Night's Dream from the English Touring Opera

- Midsummer Night's Dream from the Britten-Pears Foundation with audio clips