A King and No King

A King and No King is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher and first published in 1619. It has traditionally been among the most highly praised and popular works in the canon of Fletcher and his collaborators.

The play's title became almost proverbial by the middle of the 17th century, and was used repeatedly in the polemical literature of the mid-century political crisis to refer to the problem and predicament of King Charles I.

Date and performance

Unlike some of the problematic Beaumont/Fletcher works (see, for example, Love's Cure, or Thierry and Theodoret), there is little doubt about the date and authorship of A King and No King. The records of Sir Henry Herbert, the Master of the Revels during much of the 17th century, assert that the play was licensed in 1611 by Herbert's predecessor Sir George Buck. The drama was acted at Court by the King's Men on 26 December 1611, again in the following Christmas season, and again on 10 January 1637.

Publication

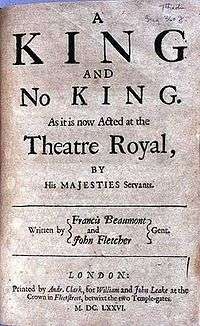

The play was entered into the Stationers' Register on 7 August 1618.[1] The first edition was the 1619 quarto issued by the bookseller Thomas Walkley, who would publish Philaster a year later. A second quarto appeared in 1625, also from Walkley; subsequent quarto editions followed in 1631 (from Richard Hawkins), 1639, 1655, 1661, and 1676 (all from William Leake), and 1693.[2] Like other previously-printed Beaumont/Fletcher plays, A King and No King was omitted from the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647, but was included in the second of 1679.

Authorship

The authorship of the play is not disputed. Cyrus Hoy, in his survey of authorship problems in the Fletcher canon, provided this breakdown of the two dramatists' respective shares:[3]

- Beaumont — Acts I, II, and III; Act IV, scene 4; Act V, 2 and 4;

- Fletcher — Act IV, scenes 1-3; Act V, 1 and 3

— a division that agrees with the conclusions of earlier researchers and commentators.[4]

After 1642

A staging of the popular drama was attempted during the closure of the theatres in the period of the English Civil War and the Interregnum (1642–60); a production was mounted at the Salisbury Court Theatre on 6 October 1647, only to be broken up by the authorities. As the play's publication history shows, it was popular after the Restoration. Samuel Pepys saw the play repeatedly in the early Restoration period. Charles Hart was well known for his portrayal of the protagonist, Arbaces; the 1676 quarto included a cast list that mentions Hart and other prominent actors of the era, including Edward Kynaston and Michael Mohun. The play remained in the active repertory well into the 18th century.[5]

John Dryden was an admirer of A King and No King; his own play Love Triumphant (1694) bears a strong resemblance to the Beaumont/Fletcher work. Also influenced by the play was Mary Pix, when she wrote her The Double Distress (1701).[6]

Synopsis

Arbaces, King of Iberia, has been abroad, fighting in the wars, for many years; he returns home in triumph, bringing with him Tigranes, the defeated king of Armenia. He intends to marry his sister Panthea to Tigranes. Meanwhile, he learns that his mother, Arane, who hates him, has plotted his assassination. The regent Gobrius has foiled the plot. Tigranes' fiancee Spaconia accompanies him into exile, hoping to avert Arbaces' plans for the marriage alliance. Tigranes promises her he will remain faithful.

On his return Arbaces finds that he now has a powerful sexual attraction to his beautiful sister, the princess Panthea, whom he hasn't seen since childhood. Much of the play depicts his increasingly desperate struggle against his incestuous passion. Arbaces blames the protector Gobrius for his predicament; the minister had written Arbaces many letters during the king's years abroad, praising Panthea's beauty and her love for him. Panthea is also attracted to Arbaces, but her virtue restains them both. The king becomes so desperate that he decides to murder Gobrius, rape Panthea, and then commit suicide. Meanwhile, Tigranes too falls in love with Panthea, even though this means he breaks his faith with Spaconia. Tigranes exercises the self-discipline and rationality that Arbaces struggles to achieve, and rededicates himself to Spaconia.

Arbaces' dilemma is resolved when it is revealed that the situation is a complex hoax, staged by Arane and Gobrius to give an heir to the childless old king who was Arbaces' predecessor. Arane's plots against her supposed son were intended to restore the rightful succession. Arbaces is in fact Gobrius's son, and so Panthea is not actually his sister. Gobrius had plotted that his son would become the legitimate king, by marriage with Panthea; Arbaces does marry the princess, but steps down from the kingship.

Arbaces is presented as a mixed character, brave and formidable in battle, but boastful and somewhat vulgar. His character is explained by the trick of his birth: he cannot behave with the nobility of a king, because he isn't one by "blood." The comic relief in the play is provided by the cowardly Bessus and his cronies; their subplot turns on the customs of honorable duelling — and their comical violation. (Bessus was a well-known comic creation; Queen Henrietta Maria refers to Bessus in a 25 February 1643 letter to her husband, Charles I.)[7]

A King and No King has a strong degree of commonality with the same authors' Thierry and Theodoret. The former might be regarded as the tragicomic version, and the latter the tragic, of the same story.

Critical responses

The play's prominence has earned it abundant attention from generations of critics.[8] Its "distinctiveness" has been described as "a firestorm of theatrical tricks meant to indulge the erotic fantasies and jaded tastes of Jacobean audiences..," combined with a "philosophical drama...of substantive political and ideological concerns."[9] The play constitutes a study of the consequences of royal intemperance in an absolute monarchy.

References

- ↑ E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923; Vol. 3, p. 225.

- ↑ Alfred Claghorn Potter, A Bibliography of Beaumont and Fletcher, Cambridge, MA, Library of Harvard University, 1890; p. 9.

- ↑ Terence P. Logan and Denzell S. Smith, eds., The Later Jacobean and Caroline Dramatists: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama, Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1978; pp. 59-60.

- ↑ E. H. C. Oliphant, The Plays of Beaumont and Fletcher: An Attempt to Determine Their Respective Shares and the Shares of Others, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1927; pp. 167-9.

- ↑ Arthur Colby Sprague, Beaumont and Fletcher on the Restoration Stage, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1926; pp. 3, 16, 18, 35 and ff.

- ↑ Margarete Rubik, Early Women Dramatists, 1550–1800, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 1998; pp. 83-4.

- ↑ Logan and Smith, p. 33.

- ↑ Logan and Smith, pp. 10, 12, 32-3, 37 and ff.

- ↑ David Laird, "'A curious way of torturing': language and ideological transformation in A King and No King," in: Drama and Philosophy, edited by James Redmond; Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990; pp. 107-8.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||