A Gest of Robyn Hode

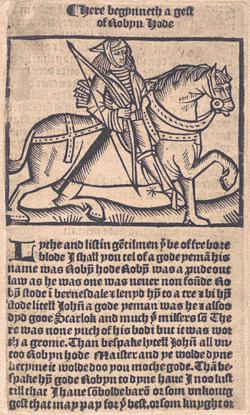

"A Gest of Robyn Hode" is Child Ballad 117; it is also called A Lyttell Geste of Robyn Hode in one of the two oldest books that contain it.[1]

It is one of the oldest surviving tales of Robin Hood, printed between 1492 and 1534, but shows every sign of having been put together from several already-existing tales. James Holt believes A Gest of Robyn Hode was written in approximately 1450.[2] It is a lengthy tale, consisting of eight fyttes, or sections.[3] It is a ballad written in Middle English.[4]

It is also a type of “The Good Outlaw” tale, in which the hero of the story is an outlaw who commits actual crimes, but the outlaw is still supported by the people. The hero in the tale has to challenge a corrupt system, which has committed wrongs against the hero, his family, and his friends. As the outlaw, the individual has to depict certain characteristics, such as loyalty, courage, and cleverness, as well as be a victim of a corrupt legal or political system. However, the outlaw committing the crimes shows he can outwit his opponent and show his moral integrity, but he cannot commit crimes for the sake of committing crimes.[5]

Background

A Gest of Robyn Hode is a premier example of romanticizing the outlaw using courtly romance, in order to illustrate the corruption of the law. As John Taylor writes, “The targets of Robin Hood’s criticism are the justices of the forest and the common law, against whom grievances could have been felt by more than one section of the medieval community.”[6] It is believed the tale was performed by minstrels, since the tale contains a narrative voice addressing the audience on several occasions. The audience is believed to have been from the second Class, who would have jobs as yeomen, apprentices, merchants, journeymen, laborers, and small proprietors.

Most scholars believe the tale to be a compilation of stories creating a heroic ballad using previous tales, such as The Legend of Eustace Monk, a forest renegade who was also an outlawed nobleman and a trickster.[7] Although the tale is thought to have been written in the 15th century, it appears to be set in the 1330s or 1340s – that is, the early part of the reign of King Edward III.[8]

The text is unique, in that it provides details relating to the 13th century, such as legal, social, and military structures, but it also includes allusions to medieval geography and locations known during the fifteenth century. There are disagreements to whether Robyn Hode was a yeoman or a man from the lower gentry class.

Likewise, there was an outlaw from Berkshire, in 1262, which had the alias, “Robehod.” There was also a ship in Aberdeen in 1438, which was called “Robene Hude.”[9] The first mention of the poem of Robyn Hode is seen in William Langland’s Piers Plowman written in 1377.[10]

Synopsis

Robin Hood refuses to eat unless he has a guest. Little John finds a sorrowful knight and compels him to come. When Robin asks how much money he has, the knight says he has ten shillings. They demand to know how this came about, and the knight explains that his son killed two men, and he had to spend all his money, and mortgage his land, to save him. Robin lends him the required four hundred pounds on the security of St. Mary, and the rest of the band – Little John, Much the Miller's Son, and Will Scarlet – insist on giving him fine clothing, a packhorse, and a courser as well, and because a knight should have an attendant, Little John goes with him.

The knight pretends that he still has not acquired the gold and pleads with the abbot for mercy. The abbot insists on payment, and the knight reveals his deception and pays him, telling him that had the abbot shown leniency, the knight would have rewarded him. Afterward, the knight saves money to repay Robin, and also obtains a hundred bows, with arrows fletched with peacock feathers. As he is travelling back to Robin's base in order to repay him, he rides past a wrestling match, where he sees a yeoman who has won the fight but, because he is a stranger, is likely to be killed by the angry crowd, and so the knight saves him.

Whilst still in the service of the knight, Little John goes to an archery contest and wins. The sheriff takes him into his service, after Little John is given leave by the knight. One day, Little John wakes late and wants to eat. The steward ("stuarde"), who is the butler ("bottler"), and the cook try to stop him because it is not mealtime. The cook puts up a good fight and Little John proposes that he should come to the forest and join the band of outlaws. He agrees and feeds Little John. They plunder the house and go to Robin. There, Little John tricks the sheriff into coming to Robin. Robin only permits the sheriff to leave when he has sworn to do them no harm.

Robin again refuses to eat unless he has a guest. The men catch a monk from St. Mary's Abbey who after the feast claims to have only twenty marks, while he is actually carrying eight hundred pounds; Robin claims it for his own, stating that St. Mary has sent it to him — as he is still owed the money he has lent to the knight — and has graciously doubled the amount. Later on, the knight arrives. He explains that he is late because he has saved the yeoman at the wrestling competition; Robin tells him that whoever helps a yeoman is his friend, and refuses to accept the knight's repayment. When the knight gives him the bows, Robin pays him half the eight hundred pounds.

The sheriff holds an archery contest, in which Robin and his men take part. All the band acquit themselves well, but Robin wins. The sheriff tries to seize him, but they escape to the castle of Sir Richard at the Lee, the knight who was helped by Robin (and who is first named at this point), and the sheriff cannot break in. He brings the matter before the king, who insists that both the knight and Robin must be brought to justice. The sheriff takes Sir Richard prisoner whilst the latter is hunting, and Sir Richard's wife goes to Robin for help. They stage a rescue, in the process of which Robin shoots and kills the sheriff.

The king comes to take Robin and is outraged by the damage to his deer. He promises Sir Richard's land to whoever kills the knight, and is told that no one could hold the land while Robin Hood is at large. After months, he is persuaded to disguise himself and some men as monks, and thus get Robin to capture them, which Robin does, taking half of their forty pounds. The "abbot" hands him an invitation from the king to dine at Nottingham. For that, Robin says he would dine with them. After the meal, they set up an archery contest, and whoever fails to hit the target has to suffer a blow. Robin misses and has the "abbot" deliver the blow. The king knocks him down and reveals himself. Robin, his men, and Sir Richard all kneel in homage.

The king takes Robin with him to lead a life at court. However, after a short while, Robin longs for the forest and returns home, defying the king (who has only given him leave for a week). Robin regathers his band of outlaws, and they live in the forest for twenty-two years.

A prioress finally kills Robin, at the instigation of her lover Roger, by treacherously bleeding him excessively. The tale ends with praise for Robin, who "dyde pore men moch god."[11]

Adaptations

Many portions of this tale have reappeared in later versions. Some appeared in other ballads: the king's insistence on the capture and the archery contest to catch Robin in Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow (though in the opposite order), the rescue in Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly and Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires, the king's intervention in The King's Disguise, and Friendship with Robin Hood, and the final murder in Robin Hood's Death. Variations of the theme of robbing the monk were the basis for two later related ballads, "Robin Hood and the Bishop" and "Robin Hood and the Bishop of Hereford".[12]

Howard Pyle and other retellers of the Robin Hood stories have included many of them. The king's visit is, in fact, in virtually every version that purports to tell the entire story.

The archery contest is a standard in filmed adaptions of the legends. The Sheriff usually sees through Robin's disguise, leading to a fight scene between his men and the outlaws (who are hidden in the crowd). Examples include:

- The Adventures of Robin Hood, where Prince John sets the tournament as a trap, and Robin is captured, to be rescued in another fight when he is to hang.

- Walt Disney's animated Robin Hood, in which Robin (a fox) disguises himself as a stork.

- The pilot episode of Robin of Sherwood (Robin Hood and the Sorcerer), in which the prize is a magical silver arrow, sacred to Herne the Hunter.

- Episode two of the children's comedy Maid Marian and Her Merry Men is a parody of this story. Robin of Kensington disguises himself in a chicken outfit, and enters the contest as "Robert the Incredible Chicken". However, because Marian is a better archer, the Sheriff concludes she must be Robin in disguise.

- In episode five of the 2006 Robin Hood TV series, Robin decides not to enter the archery contest, recognising that it is a trap. He is subsequently persuaded by Marian to disguise himself as one of the legitimate entrants to ensure Guy of Gisbourne's man does not win the prize.

In later versions of the story, Robin sometimes wins by splitting an opponent's arrow down the middle. Other versions of the archery contests do not include the fight; often, as in Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow, the disguises succeed in fooling the sheriff. Still further divergences have appeared. In Walt Disney's live-action film The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men, Robin and his father win such a contest, but as Prince John staged it to find archers for his service and both of them refuse, Prince John tries to have them killed; his father dies, and Robin is outlawed for defending himself. In Robin Hood's Progress to Nottingham, Robin is going to a shooting contest when he has the conflict that leads to his being outlawed.

Elements of the Gest appear in many episodes of the 1955 The Adventures of Robin Hood TV series. Most notable are "The Knight Who Came to Dinner" (featuring Sir Richard's debt to an abbot) and "The Challenge" (with features not only the archery contest but the outlaws taking refuge in Sir Richard's castle).

"Herne's Son", an episode of the Robin of Sherwood TV series, also has Sir Richard in debt to the Abbot of St. Mary's.

Many elements of the Gest, including the knight's debt, form a major part of the Robin McKinley novel, The Outlaws of Sherwood.

Bob Frank has recorded the entire Gest on a CD, in a modern English version entitled "A Little Gest of Robin Hood." (Bowstring Records, 2002) He performs it with a guitar, in a "talking blues" style.

Rhyme:

Lythe and listin gentilmen That be of frebore blode I shall you tel of a gode yeman His name was Robyn Hode 12:44 Lyth and lystyn gentilmen All that nowe be here Of Litell Johnn that was the knightes man Goode myrth ye shall here

References

- ↑ Holt, J. C. Robin Hood p 25 (1982) Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27541-6.

- ↑ Holt, J. C. Robin Hood p 15 (1982) Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27541-6.

- ↑ Holt, J. C. Robin Hood p 17 (1982) Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27541-6.

- ↑ Taylor, John. “Robin Hood.” Dictionary of the Middle Ages. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988.

- ↑ Ohlgen, Thomas H., ed. “The Gest of Robyn Hode.” Medieval Outlaw: The Tales in Modern English. Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing, 1998. p. 216-238.

- ↑ Taylor, John. “Robin Hood.” Dictionary of the Middle Ages. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988

- ↑ Bessinger, Jr., J. B. “The Gest of Robin Hood Revisited.” Robin Hood: An Anthology of Scholarship and Criticism. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1999. p.39-50.

- ↑ Ohlgen, Thomas H., ed. “The Gest of Robyn Hode.” Medieval Outlaw: The Tales in Modern English. Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing, 1998. p. 216-238.

- ↑ Taylor, John. “Robin Hood.” New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988.

- ↑ Barrie Dobson. "Robin Hood" Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Ed. André Vauchez. © 2001 by James Clarke & Co. Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages (e-reference edition). Distributed by Oxford University Press. John Carroll University. 10 March 2008. http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t179.e2457.

- ↑ Gest, line 1824.

- ↑ Child, Francis James (1904) English and Scottish Popular Ballads, p. 338. Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Holt, J. C. (1982). Robin Hood. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27541-6.

- Knight, Stephen (1994). Robin Hood. A Complete Study of the English Outlaw. Blackwell.

- Knight, Stephen and Thomas H. Ohlgren. “A Gest of Robyn Hode: Introduction.” Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

- Pollard, A. J. (2004). Imagining Robin Hood. The Late-Medieval Stories in Historical Context. Routledge.

External links

- A Gest of Robyn Hode

- A Gest of Robyn Hode: Introduction

- A Little Geste of Robin Hood and his Meiny (in modern English spelling)