A. Bartlett Giamatti

| A. Bartlett Giamatti | |

|---|---|

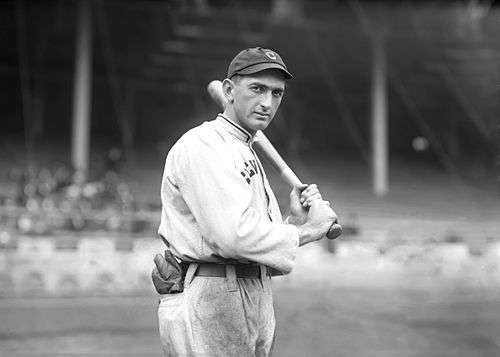

Giamatti in 1989 | |

| Born |

Angelo Bartlett Giamatti April 4, 1938 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

September 1, 1989 (aged 51) Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Residence | Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Yale College |

| Alma mater | Phillips Academy |

| Occupation |

President of Yale University (1978–1986) National League President (1986–1989) MLB Commissioner (April 1, 1989–September 1, 1989) |

| Home town | Boston, Massachusetts |

| Spouse(s) | Toni Marilyn Smith |

| Children |

Paul Giamatti Marcus Giamatti Elena Giamatti |

| Parent(s) |

Valentine John Giamatti (father) Mary Claybaugh Walton (mother) |

| 7th Commissioner of Baseball | |

|---|---|

|

In office April 1, 1989 – September 1, 1989 | |

| Preceded by | Peter Ueberroth |

| Succeeded by | Fay Vincent |

Angelo Bartlett "Bart" Giamatti (/dʒiːəˈmɑːti/; April 4, 1938 – September 1, 1989) was an American professor of English Renaissance literature, the president of Yale University, and the seventh Commissioner of Major League Baseball.

Giamatti served as Commissioner for only five months before dying suddenly of a heart attack. He is the shortest-tenured baseball commissioner in the sport's history and the only holder of the office not to preside over a full Major League Baseball season. Giamatti is best remembered today for negotiating the agreement resolving the Pete Rose betting scandal by permitting Rose to voluntarily withdraw from the sport to avoid further punishment.

Personal life

Giamatti was born in Boston and grew up in South Hadley, Massachusetts, the son of Mary Claybaugh Walton (Smith College '35) and Valentine John Giamatti. His father was professor and chairman of the Department of Italian Language and Literature at Mount Holyoke College.[1] Giamatti's paternal grandparents were Italian immigrants Angelo Giammattei (Italian pronunciation: [dʒammaˈttɛi]) and Maria Lavorgna (Italian pronunciation: [laˈvɔrɲa]): his grandfather Angelo emigrated to the United States from Telese, near Benevento, Italy, around 1900.[2] Giamatti's maternal grandparents, from Wakefield, Massachusetts, were Helen Buffum (Davidson) and Bartlett Walton, who graduated from Phillips Academy Andover and Harvard College.

Giamatti attended South Hadley High School, spent his junior year at the American Overseas School of Rome, and graduated from Phillips Academy in 1956. At Yale College, he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon (Phi chapter) and as a junior in 1960 was tapped by Scroll and Key,[3] a senior secret society. He graduated magna cum laude in 1960. That same year, he married Toni Marilyn Smith, who taught English for more than 20 years at the Hopkins School in New Haven, Connecticut, until her death in 2004.[4] Together the couple had three children: Hollywood actors Paul and Marcus and jewelry designer Elena. In the film Sideways, a photograph of the character Miles Raymond (portrayed by Giamatti's son Paul) with his late father is really a picture of Paul and Bart Giamatti.

Giamatti's friend and successor as baseball commissioner, Fay Vincent, wrote in The Last Commissioner that Giamatti's official religious view was agnosticism.

Yale

Giamatti stayed in New Haven to receive his doctorate in 1964, when he also published a volume of essays by Thomas G. Bergin he had coedited with a philosophy graduate student, T. K. Seung. He became a professor of comparative literature at Yale University, an author, and master of Ezra Stiles College at Yale, a post to which he was appointed by his predecessor as Yale president, Kingman Brewster, Jr.. Giamatti taught briefly at Princeton but spent most of his academic life at Yale. Giamatti's scholarly work focused on English Renaissance literature, particularly Edmund Spenser, and relationships between English and Italian Renaissance poets. His writings on the pastoral influence in literature and the effect of Ludovico Ariosto on English literature remain influential.

As a teacher of undergraduates, he was well known, and rejected the conventional wisdom that the Renaissance represented an abrupt cultural change, stressing the continuities between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. He sometimes referred to the Protestant Reformation as the "Protestant Deformation."

When Giamatti's tenure as Stiles master ended in 1972, he was so popular that his students wanted to honor him with a present. Giamatti told them he wanted a joke gift and they got him a moosehead (from a yard sale), which was ceremoniously hung in the dining hall.

Giamatti served as president of Yale University from 1978 to 1986. He was the youngest president of the university in its history and presided over the university during a bitter strike by its clerical and technical workers in 1984-85. As university president, he refused student, faculty, and community demands to divest from apartheid South Africa. He also served on the board of trustees of Mount Holyoke College for many years, participating fully despite his Yale and baseball commitments. Giamatti was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1980.[5]

Baseball

Giamatti had a lifelong interest in baseball (he was a die-hard Boston Red Sox fan). In 1978, when he was first rumored to be a candidate for the presidency of Yale, he had deflected questions by observing that "The only thing I ever wanted to be president of was the American League." His article "Tom Seaver's Farewell", published in Harper's Magazine in September 1977 and "Baseball and the American Character" published in that magazine in October 1986 are but two of many of his baseball publications. Giamatti became president of the National League in 1986, and later commissioner of baseball in 1989. During his stint as National League president, Giamatti placed an emphasis on the need to improve the environment for the fan in the ballparks. He also decided to make umpires strictly enforce the balk rule and supported "social justice" as the only remedy for the lack of presence of minority managers, coaches, or executives at any level in Major League Baseball.

While still serving as National League president, Giamatti suspended Pete Rose for 30 games after Rose shoved umpire Dave Pallone on April 30, 1988. Later that year, Giamatti also suspended Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Jay Howell for three days, who was caught using pine tar during the National League Championship Series.

Giamatti, whose tough dealing with Yale's union favorably impressed Major League Baseball owners, was unanimously elected to succeed Peter Ueberroth as commissioner on September 8, 1988.[7] Determined to maintain the integrity of the game, on August 24, 1989, Giamatti (who took office on April 1, 1989) prevailed upon Pete Rose to agree voluntarily to remain permanently ineligible to play baseball.[8]

Death

While at his vacation home on Martha's Vineyard, Giamatti, a heavy smoker for many years, died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 51, just eight days after banishing Pete Rose and 154 days into his tenure as commissioner.[9] He became the second baseball commissioner to die in office, the first being Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Baseball's owners soon selected Fay Vincent, Giamatti's close friend and baseball's first-ever deputy commissioner, as the new commissioner.

On October 14, 1989, before Game 1 at the World Series, Giamatti—to whom this World Series was dedicated—was memorialized with a moment of silence. Son Marcus Giamatti threw out the first pitch before the game. Also before Game One, the Yale Whiffenpoofs sang the national anthem, a blend of "The Star-Spangled Banner" with "America the Beautiful" that has been since repeated by other a cappella groups.

Prior to the first game of the 1990 Major League Baseball season, played at Fenway Park, Toni Giamatti threw out the ceremonial first pitch. She would perform the honors again prior to Game 7 of the 1997 World Series.

The Little League Eastern Regional Headquarters in Bristol, Connecticut is named after Giamatti.[10] One of the three awards given annually by Major League Baseball's Baseball Assistance Program is named the "Bart Giamatti Award." Giamatti was inducted into the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in 1992.[11] James Reston, Jr. notes in his book Collision at Home Plate: The Lives of Pete Rose and Bart Giamatti that Giamatti suffered from Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, an inherited neuromuscular disease affecting peripheral nerves.

Works

- Master Pieces from the Files of T.G.B., ed. Thomas K. Swing and A. Bartlett Giamatti (1964).

- The Earthly Paradise and the Renaissance Epic (1966)

- Play of Double Senses: Spenser’s Faerie Queene (1975)

- The University and the Public Interest (1981)

- Exile and Change in Renaissance Literature (1984)

- Take Time for Paradise: Americans and their Games (1989)

- A Free and Ordered Space: The Real World of the University (1990)

- A Great and Glorious Game: Baseball Writings of A. Bartlett Giamatti (ed. Kenneth Robson, 1998)

See also

Further reading

- Kelley, Brooks Mather. (1999). Yale: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07843-5; OCLC 810552

- Reston, James. (1991). Collision at Home Plate: The Lives of Pete Rose and Bart Giamatti.

- Valerio, Anthony. (1991). A Life of A. Bartlett Giamatti: By Him and About Him.

References

- ↑ The Giammati Collection at MHC

- ↑ LaGumina, Salvatore J.; et al. (2000). The Italian American Experience: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland. pp. 263–264.

- ↑ Notable members

- ↑ Ward, Patrick D. "Former first lady of Yale passes away," Archived May 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Yale Daily News. September 23, 2004.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780-2010: Chapter G" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ↑ "MLB won't reinstate Shoeless Joe Jackson". ESPN. September 1, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ Sports Encyclopedia

- ↑ Rose agreement

- ↑ New York Times obituary

- ↑ PDF (englisch)

- ↑ A. Bartlett Giamatti in der NIASHF

External links

- "The Green Fields of the Mind", excerpt from A Great and Glorious Game

- BaseballLibrary – profile and events

- A. Bartlett Giamatti Quotations

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Hanna Holborn Gray, acting |

President of Yale University 1977–1986 |

Succeeded by Benno C. Schmidt, Jr. |