369th Infantry Regiment (United States)

| 15th New York National Guard Regiment

369th Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

|

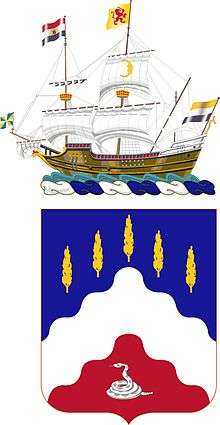

Coat of arms | |

| Active | 1913–1945 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Nickname(s) | "The Harlem Hellfighters" |

| Motto(s) | "Don't Tread On Me" |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. |

| Insignia | |

| DUI |

|

The 369th Infantry Regiment, formerly known as the 15th New York National Guard Regiment, was an infantry regiment of the United States Army National Guard during World War I and World War II. The Regiment consisted of African Americans as well as Puerto Ricans and was known for being the first African American regiment to serve with the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I. Before the 15th New York National Guard Regiment was formed, any African American that wanted to fight in the war had to enlist in the French or Canadian armies.[2] The regiment was nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters, the Black Rattlers and the Men of Bronze, which was given to the regiment by the French.[3] The nickname "Hell Fighters" was given to them by the Germans due to their toughness and that they never lost a man through capture, lost a trench or a foot of ground to the enemy.[4] The "Harlem Hellfighters" were the first all-black regiment who helped change the American public's opinion on African American soldiers and paved the way for future soldiers of color.

Background

On 5 October 1917 long time secretary to Booker T. Washington, Emmett J. Scott was appointed Special Assistant to Newton D. Baker, the Secretary of War. Emmett was to serve as a confidential advisor in situations that involved the well-being of ten million African-Americans and their roles in the war. While many African Americans who served in the Great War believed that, upon returning home racial discrimination would dissipate, that did not happen. Racial hatred after World War I was probably at its worst until the start of the Second World War.[5] So with this American discrimination of African American soldiers, these troops were often sent to Europe where they were used to fill vacancies in the French Armies. Unlike the British, the French held high opinions of black soldiers which made for a more positive environment when working together. Ironically this made African American troops more passionate about fighting for America.[6] This newly created patriotism by African Americans then led to the creation of the 369th Infantry Regiment.

Although many African Americans were eager to fight in the war, they were being turned away from military service. When America realized that they did not have close to enough soldiers, they decided to pass the selective service act which required all men from the age 21-31 to enlist in the draft. Additionally, they decided to allow African Americans to enlist as well. This would give African Americans the opportunity that they needed to try and change the way they were perceived by white America.[7]

The 369th Regiment was formed from the National Guard's 15th Regiment in New York. The 15th Regiment was formed after Charles S. Whitman was elected Governor of New York. He enforced the legislation that was passed due to the efforts of the 10th Cavalry in Mexico which had passed as a law that had not manifested until 2 June 1913.[6]

Once the United States entered into World War I, many African Americans believed that entering the armed forces would help eliminate racial discrimination throughout the United States. Many African Americans felt that it was "a God-sent blessing" so that they could prove that they deserved respect from the white Americans through service in the armed forces. Through the efforts of the Central Committee of Negro College Men and President Wilson, a special training camp to train black officers for the proposed black regiments was established.[8]

History

The 369th Infantry Regiment was constituted 2 June 1913 in the New York Army National Guard as the 15th New York Infantry Regiment. The 369th Infantry was organized on 29 June 1916 at New York City. The infantry was called into Federal service on 25 July 1917 at Camp Whitman, New York. While at Camp Whitman, the 369th Infantry learned basic military practices. These basics included military courtesy, how to address officers and how to salute. Along with these basics they also learned how to stay low and out of sight during attacks, stand guard and how to march in formation. After their training at Camp Whitman, the 369th was called into active duty in New York. While in New York, the 369th was split into three battalions in which they guarded rail lines, construction sites and other camps throughout New York. Then on 8 October 1917 the Regiment traveled to Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina, where they received training in actual combat. Camp Wadsworth was set up similar to the French battlefields.[1] While at Camp Wadsworth they experienced significant racism from the local communities and from other units. There was one incident in which two soldiers from the 15th Regiment, Lieutenant Europe and Noble Sissle, were refused by the owner of a shop when they attempted to buy a newspaper. Several soldiers from the white 27th Division came to aid their fellow soldiers. Lieutenant Europe had commanded them to leave before violence erupted. There were many other shops that refused to sell goods to the members of the 15th Regiment, so members of the 27th and 71st Divisions told the shop owners that if they did not serve black soldiers that they can close their stores and leave town. The white soldiers then stated "They're our buddies. And we won't buy from men who treat them unfairly."[9]

The 15th Infantry Regiment NYARNG was assigned on 1 December 1917 to the 185th Infantry Brigade. It was commanded by Col. William Hayward, a member of the Union League Club of New York, which sponsored the 369th in the tradition of the 20th U.S. Colored Infantry, which the club had sponsored in the Civil War. The 15th Infantry Regiment shipped out from the New York Port of Embarkation on 27 December 1917, and joined its brigade upon arrival in France. The unit was relegated to labor service duties instead of combat training. The 185th Infantry Brigade was assigned on 5 January 1918 to the 93rd Division [Provisional].

The 15th Infantry Regiment, NYARNG was reorganized and re-designated on 1 March 1918 as the 369th Infantry Regiment, but the unit continued labor service duties while it awaited a decision as to its future.

The US Army decided on 8 April 1918 to assign the unit to the French Army for the duration of the United States' participation in the war; this regiment was assigned to French Army command because many white American soldiers refused to perform combat duty with black soldiers.[10] The men were issued French weapons,[11] helmets, and brown leather belts and pouches, although they continued to wear their U.S. uniforms. While in the United States, the 369th Regiment was never treated like similar all white units. They were subject to intense racial discrimination and were looked down upon. This regiment suffered considerable harassment by both individual white American soldiers and even denigration by the American Expeditionary Force headquarters which went so far as to release the notorious pamphlet Secret Information Concerning Black American Troops, which "warned" French civilian authorities of the alleged inferior nature and supposed rapist tendencies of African Americans.[12]

In France, the 369th was treated as if they were no different from any other French unit. The French did not show hatred towards them and did not racially segregate the 369th. The 369th finally felt what it was like to be treated equally. The French accepted the all black 369th Regiment with open arms and welcomed them to their country.[5] The French were less concerned with race than the Americans and were short on troops.[11]

The 369th Infantry Regiment was relieved 8 May 1918 from assignment to the 185th Infantry Brigade, and went into the trenches as part of the French 16th Division. It served continuously to 3 July. The regiment returned to combat in the Second Battle of the Marne. Later the 369th was reassigned to Gen. Lebouc's 161st Division to participate in the Allied counterattack. On one tour they were out for over 6 months which was the longest deployment of any unit in World War I.[13] On 19 August, the regiment went off the line for rest and training of replacements.

While overseas the Hellfighters saw propaganda intended for them. It claimed that the Germans had done nothing wrong to blacks, and that they should instead be fighting against the Americans who had oppressed them for years. These statements only made the Hellfighters even more devoted to the U.S.[14]

On 25 September 1918 the French 4th Army went on the offensive in conjunction with the American drive in the Meuse–Argonne. The 369th turned in a good account in heavy fighting, sustaining severe losses. They captured the important village of Séchault. At one point the 369th advanced faster than French troops on their right and left flanks, and risked being cut off. By the time the regiment pulled back for reorganization, it had advanced 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) through severe German resistance.

In mid-October the regiment was moved to a quiet sector in the Vosges Mountains. It was there on 11 November, the day of the Armistice. Six days later, the 369th made its last advance and on 26 November, reached the banks of the river Rhine, the first Allied unit to reach it. The regiment was relieved on 12 December 1918 from assignment to the French 161st Division. It returned to the New York Port of Embarkation and was demobilized on 28 February 1919 at Camp Upton at Yaphank, New York, and returned to the New York Army National Guard.

Two Medals of Honor and many Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded to members of the regiment. The most celebrated man in the 369th was Pvt. Henry Johnson, a former Albany, New York, rail station porter, who earned the nickname "Black Death" for his actions in combat in France. In May 1918 Johnson and Pvt. Needham Roberts fought off a 24-man German patrol, though both were severely wounded. After they expended their ammunition, Roberts used his rifle as a club and Johnson battled with a bolo knife. Reports suggest that Johnson killed at least four German soldiers and might have wounded 30 others.[15] Usually black achievements and valor went unnoticed, despite that fact over 100 men from the 369th were presented with American and/or French medals. Among those honors[13] Johnson was the first American to receive the Croix de Guerre awarded by the French government. This award signifies extraordinary valor.[4] By the end of the war, 171 members of the 369th were awarded the Legion of Honor or the Croix de Guerre.[16]

Photographs show that the 369th carried the New York Regimental flag overseas. The French government awarded the regiment the Croix de Guerre with silver star for the taking of Séchault. It was pinned to the colors by General Lebouc at a ceremony in Germany, 13 December 1918.

One of the first units in the United States armed forces to have black officers in addition to its all-black enlisted corps, the 369th compiled a war record equal to any other U.S. infantry regiment. It earned several unit citations along with many individual decorations for valor from the French government. The 369th Infantry Regiment was the first New York unit to return to the United States, and was the first unit to march up Fifth Avenue from the Washington Square Park Arch to their armory in Harlem. Their unit was placed on the permanent list with other veteran units.

In re-capping the story of the 369th Arthur W. Little, who had been a battalion commander, wrote in the regimental history From Harlem to the Rhine, that it was official that the outfit was 191 days under fire, never lost a foot of ground or had a man taken prisoner, though on two occasions men were captured but they were recovered. Only once did it fail to take its objective and that was due largely to bungling by American headquarters support.

So by the end of the 369th Infantry's campaign in World War I they were present in the Champagne – Marne, Meuse – Argonne, Champagne 1918, Alsace 1918 campaigns in which they suffered nearly 1,500 casualties.[17] The 369th also fought in distinguished battles such as Belleau Wood and Chateau-Thierry. While fighting these battles, they served nearly six months on the front lines and earned many distinguished awards. These awards included the Croix de Guerre which is France's highest military honor.[18]

369th Regiment Marching Band

The 369th Regiment band was relied upon not only in battle but also for morale. So by the end of their tour they became one of the most famous military bands throughout Europe. They followed the 369th overseas and were highly regarded and known for being able to immediately boost morale. While overseas the 369th Regiment made up less than 1% of the soldiers deployed, but were responsible for over 20% of the territory of all the land assigned to the United States.[6] During the war the 369th's regimental band (under the direction of James Reese Europe) became famous throughout Europe. It introduced the until-then unknown music called jazz to British, French and other audiences, and started an international demand for it.[19]

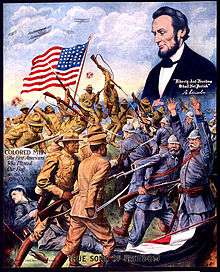

_369th_Infantry_(old_15th_National_Guard_of_New_York_Cit_._._._-_NARA_-_533553.tif.jpg)

At the end of the war, the 369th returned to New York City, and on 17 February 1919, paraded through the city.[20] This day became an unofficial holiday of sorts for all of Harlem. Many black school children were dismissed from school so that they could attend the parade.[21] With the addition of many adults there were thousands of people that lined the streets to see the 369th Regiment: the parade began on Fifth Avenue at 61st Street, proceeded uptown past ranks of white bystanders, turned west on 110th Street, and then turned onto Lenox Avenue, and marched into Harlem, where black New Yorkers packed the sidewalks to see them. The parade became a marker of African American service to the nation, a frequent point of reference for those campaigning for civil rights. There were multiple parades that took place throughout the nation, many of these parades included all black regiments, including the 370th from Illinois. Then in the 1920s and 1930s, the 369th was a regular presence on Harlem's streets, each year marching through the neighborhood from their armory to catch a train to their annual summer camp, and then back through the neighborhood on their return two weeks later.[22]

Coast Artillery lineage

After the first World War, the regiment was spread out throughout New York and still maintained some military exercises. Then with the start of the second World War, they were reorganized as the 369th Antiaircraft Artillery Regiment. They were then deployed to Hawaii and parts of the West Coast.[23]

- Constituted in the New York National Guard as 369th Coast Artillery (AA)(Coast Artillery Corps) on 11 October 1921 as follows:

- HHB from HHB 369th Infantry Regiment

- 1st Battalion from 1st Battalion 369th Infantry

- 2nd Battalion from 2nd Battalion 369th infantry

Inducted into federal service 13 January 1941 at New York City

Regiment broken up 12 December 1943 as Follows-

- HHB as 369th Antiaircraft Artillery Group (disbanded November 1944)

- 1st battalion as 369th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion (semi Mobile) (Colored) (See 369th Sustainment Brigade (United States)).

- 2nd Battalion as 870th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion. (see 970th Field Artillery Battalion.)

Honoring the 369th Infantry Regiment

In 1933 the 369th Regiment Armory was created to honor the 369th regiment for their service. This armory stands at 142nd and Fifth Avenue, in the heart of Harlem. This armory was constructed starting in the 1920s and was completed in the 1930s.[24] The 369th Regiment Armory was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.[25]

The infantry's polished post-World War I reputation was not completely safe from external criticism, which ultimately surfaced as a result of ongoing racial tension in the United States. In 1940 the Chicago Defender reported that the United States Department of War arranged for the 369th regiment to be renamed the 'Colored Infantry'. The department announced that there were too many infantry units in the national guard and the 369th regiment would be among those slated to go, the first alleged step toward abolishing the famed unit. Supporters of the regiment swiftly objected to the introduction of racial identity in the title of a unit in the United States army, effectively preserving the regiment's reputation.[26]

In 2003 the New York State Department of Transportation renamed the Harlem River Drive as the "Harlem Hellfighters Drive".[27] On 29 September 2006 a twelve foot high monument was unveiled to honor the 369th Regiment. This statue is a replica of a monument that stands in France. The monument is made of black granite and contains the 369th crest and rattlesnake insignia[28]

Descending units of the 369th Infantry Regiment have continued to serve since World War I. The 369th Infantry Regiment continued to serve up until World War II where they would be reorganized into the 369th Anti-aircraft Artillery Regiment. The newly formed regiment would serve in Hawaii and throughout much of the West Coast. Subsequently, the 369th Anti-aircraft Artillery Regiment would also be reformed into the present-day 369th Sustainment Brigade.[29][30]

Notable soldiers

- Benjamin O. Davis Sr., Regimental Commander of the 369th Regiment (1938) and first African-American general (1941) in the US Armed Forces.

- James Reese Europe, an early ragtime and jazz bandleader and composer, who served as regimental bandmaster as part of the Harlem Hellfighters who led the first Americans into France, then into Germany after the Armistice. He also established the first African-American musicians union the Clef Club.[31]

- Hamilton Fish III, Company Commander in the 369th Regiment, New York Congressman, and founder of the Order of Lafayette.

- Susan Elizabeth Frazier, New York City Public School teacher, President of the Women's Auxiliary of the 369th Infantry Regiment.

- Henry Johnson, recipient of the Croix de Guerre-posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Purple Heart and the Medal of Honor.

- Rafael Hernández Marín, composer of Puerto Rican music.

- Myles A. Paige, the first African American to serve as a City Magistrate in New York City, appointed by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in 1936.[32]

- Spotswood Poles, referred to as "the black Ty Cobb" for his prowess in the professional Negro baseball leagues in the early 20th century.

- Needham Roberts, recipient of the Croix de Guerre and Purple Heart.

- George Seanor Robb, one of 44 Americans to have been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for service during World War I.

- Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, tap dancer and actor

- Noble Sissle, American jazz composer, lyricist, bandleader, singer and playwright, who assisted James Reese Europe in forming the regimental band.

- Vertner Woodson Tandy, who was the first African-American to pass the military commissioning examination and was commissioned as a First Lieutenant in the 15th Infantry Regiment of the New York Guard. Tandy was also one of the founders, or "Seven Jewels," of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.

- Henry Charles Brennan Sr., Maj. (Ret.), the first African American to serve as Chief of Transportation for New York City's Department of Hospitals.

- Harry Haywood, was born in 1898, the son of slaves. Haywood's military career included service in three wars. In addition to his service in the 369th Infantry during World War I, he was a command officer in the Spanish Civil War in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and he served in the Merchant Marines during World War II, where he was active with National Maritime Union. He was a leading figure in both the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). He contributed major theory to Marxist thinking on the national question of African Americans in the United States. He was also a founder of the Maoist New Communist Movement. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Distinctive unit insignia

- Description

A silver color metal and enamel device 1 1⁄4 inches (3.2 cm) in height overall consisting of a blue shield charged with a silver rattlesnake coiled and ready to strike.

- Symbolism

The rattlesnake is a symbol used on some colonial flags and is associated with the thirteen original colonies. The silver rattlesnake on the blue shield was the distinctive regimental insignia of the 369th Infantry Regiment, ancestor of the unit, and alludes to the service of the organization during World War I.

- Background

The distinctive unit insignia was originally approved for the 369th Infantry Regiment on 17 April 1923. It was redesignated for the 369th Coast Artillery Regiment on 3 December 1940. It was redesignated for the 369th Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalion on 7 January 1944. It was redesignated for the 569th Field Artillery Battalion on 14 August 1956. The insignia was redesignated for the 369th Artillery Regiment on 4 April 1962. It was amended to correct the wording of the description on 2 September 1964. It was redesignated for the 569th Transportation Battalion and amended to add a motto on 13 March 1969. The insignia was redesignated for the 369th Transportation Battalion and amended to delete the motto on 14 January 1975. It was redesignated for the 369th Support Battalion and amended to revise the description and symbolism on 2 November 1994. The insignia was redesignated for the 369th Sustainment Brigade and amended to revise the description and symbolism on 20 July 2007.

369th Veterans' Association

The 369th Veterans' Association is a group created to honor those who served in the 369th infantry.[33] This veterans group has three distinct goals. According to the Legal Information institute of the Cornell Law Institute these include,"promoting the principles of friendship and good will among its members;engaging in social and civic activities that tend to enhance the welfare of its members and inculcate the true principles of good citizenship in its members; and memorializing, individually and collectively, the patriotic services of its members in the 369th antiaircraft artillery group and other units in the Armed Forces of the United States."[34]

In popular culture

- In 2016, the videogame Battlefield 1, set during the first World War, featured the Harlem Hellfighters as part of the single player campaign's prologue. Additionally, the collector's edition of the game included a statue of an African-American soldier from the unit.[35]

- In 2015, the regiment and its memorial in Harlem were featured in season 3, episode 3 of Mysteries at the Monument on the Travel Channel.

- In 2014, the graphic novel The Harlem Hellfighters was released, written by Max Brooks and illustrated by Caanan White. It depicts a fictionalized account of the 369th's tour in Europe during World War I.[3]

- A film adaptation of the aforementioned novel is in the works under Sony Pictures and Overbrook Entertainment.[36]

- In the CW TV series The Originals, main character Marcel Gerard served with the Harlem Hellfighters, taking command of the unit after the death of their commanding officer and turning his men into vampires when they are dying from a gas attack. He later leads them into a savage attack against the Germans. After the war, some of the Hellfighters, such as Joe Dalton, follow him back to New Orleans.

- A fictionalized version of the Harlem Hellfighters are depicted in the Charley's War graphic novel Vol. 10 The End.

- In Jazz by Toni Morrison, character Joe Trace serves in the 369th during World War I (128-129).

See also

- Coats of arms of U.S. Infantry Regiments

- Coats of arms of U.S. Air Defense Artillery Regiments

Notes

- 1 2 Nelson, Peter (2009). A More Unbending Battle: The Harlem Hellfighters' Struggle for Freedom in WWI and Equality at Home. New York: Basic Civitas. ISBN 0465003176.

- ↑ Gero (2009), p.44

- 1 2 Wang, Hansi Lo (1 April 2014). "The Harlem Hellfighters: Fighting Racism In The Trenches of WWI". NPR. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- 1 2 Gero (2009), p.56

- 1 2 Gero (2009), p.52

- 1 2 3 Gero (2009)

- ↑ "- Fighting for Respect: African-American Soldiers in WWI".

- ↑ Gero (2009), p.42

- ↑ Gero (2009), p.50

- ↑ "Editorial: For Henry Johnson, honor in sight".

- 1 2 Gilbert King. "Remembering Henry Johnson, the Soldier Called "Black Death"". Smithsonian.

- ↑ "American National Biography Online: Johnson, Henry".

- 1 2 93d Division: Summary of Operations in the World War (1944)

- ↑ Gero (2009), p.47

- ↑ Gero (2009), p.53

- ↑ Rangel, Charles B. (16 November 2011). "In Salute of the 369th Veterans' Association Harlem Hellfighters - A Congressional Recognition in Celebration of Veterans Day 11-11-11". Capitol Words. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "Chapter I: WWI." Chapter I: WWI. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 April 2014.

- ↑ "Harlem Hellfighters". MAAP: Mapping the African American Past. 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Scott, Emmett Jay, Scott's Official History, ch. XXI: "Negro Music that Stirred France", pp. 300–314.

- ↑ Lewis, William Dukes (2003). "A Brief History of African American Marching Bands". FolkStreams. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Gates, Jr., Henry Louis (2014). "Who Were the Harlem Hellfighters?". PBS. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Robertson, Stephen (1 February 2011). "Parades in 1920s Harlem". Digital Harlem Blog. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Mikkelsen, Jr., Edward (2014). "369th Infantry Regiment "Harlem Hellfighters"". The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "369th Regiment Armory, The Harlem Armory, Central Harlem". Harlem One Stop. 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "U.S. Renames 369th: Now 'Colored Infantry'". Chicago Defender. 1940. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ "Harlem River Drive: Historical Overview". NYC Roads. 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "Greenstreet: NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "Harlem Hellfighters, Harlem, NY 1913". Harlem World. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ "369th Infantry Regiment "Harlem Hellfighters"". BlackPast.org. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ The New Amsterdam Musical Association, founded in 1904, makes the NAMA the oldest African-American musical organization in the United States, but it did not admit popular musicians. The Clef Club was unique in this respect. Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lanum, Mackenzie (2014). "Paige, Myles Anderson (1898-1983)". The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Livas, Nicole (7 November 2008). "The 369th Veterans Association". WAVY Blogs. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "36 U.S. Code § 210303 - Purposes". Legal Information Institute. 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "Battlefield™ 1 Early Enlister Deluxe Edition".

- ↑ Ford, Rebecca (7 March 2014). "Sony Nabs Max Brooks' WWI Graphic Novel 'The Harlem Hellfighters'". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

References

- American Battle Monuments Commission (1944). "93d Division: Summary of Operations in the World War". The U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Bennett, John D. "Kahuku Army Air Base: One of Oahu's World War II Satellite Fields" (PDF). American Aviation Historical Society Journal (Spring 2011): 52–61.

- Gero, Anthony (2009). Black Soldiers of New York State, A Proud Legacy. State University of New York Press. p. 44. ISBN 9781441603807.

- Lee, Ulysses (1966). "United States Army in World War II Special Studies: The Employment of Negro Troops". The U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Sawicki, James A. (1991). Antiaircraft Artillery Battalions of the U.S. Army. Dumfries, VA.: Wyvern Publications. ISBN 0-9602404-7-0.

- Woodfork, Thurman P. (2014). "369th United States Infantry". 8thwood.com. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "U.S. 10th Army (Okinawa) Order of Battle, April 1945" (PDF). US Army Combined Arms Center. 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Army Institute of Heraldry document "369th Sustainment brigade".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Army Institute of Heraldry document "369th Sustainment brigade". -

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History. - EA DICE videogame developer uses African American skins and clothing that accurately resembles what a Harlem Hellfighter would be wearing. they also display a Harlem Hellfighter on the cover of their game.

Further reading

- Barbeau, Arthur E., and Florette Henri. The Unknown Soldiers; Black American Troops in World War I. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1974. ISBN 0-87722-063-8.

- Harris, Bill. The Hellfighters of Harlem: African-American Soldiers Who Fought for the Right to Fight for Their Country. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-7867-1050-0, ISBN 0-7867-1307-0.

- Harris, Stephen L. Harlem's Hell Fighters: The African-American 369th Infantry in World War I. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's, Inc, 2003. ISBN 1-57488-386-0, ISBN 1-57488-635-5.

- Little, Arthur W. From Harlem to the Rhine: The Story of New York's Colored Volunteers. New York: Covici, Friede, Publishers, 1936. (Reprinted: New York: Haskell House, 1974. ISBN 0-8383-2033-3).

- Myers, Walter Dean, and Bill Miles. The Harlem Hellfighters: When Pride Met Courage. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0-06-001136-X, ISBN 0-06-001137-8.

- Nelson, Peter. A More Unbending Battle: The Harlem Hellfighters' Struggle for Freedom in WWI and Equality at Home. New York: Basic Civitas, 2009. ISBN 0-465-00317-6.

- Sammons, Jeffrey T., and John H. Morrow, Jr. Harlem's Rattlers and the Great War: The Undaunted 369th Regiment and the African American Quest for Equality. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2014. ISBN 978-0700619573.

- Wright, Ben, “Victory and Defeat: World War I, the Harlem Hellfighters, and a Lost Battle for Civil Rights,” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, 38 (Jan. 2014) pp:35–70.

African Americans in World War I

- Scott, Emmett Jay. Scott's Official History of the American Negro in the World War. A Complete and Authentic Narration, from Official Sources, of the Participation of American Soldiers of the Negro Race in the World War for Democracy ... a Full Account of the War Work Organizations of Colored Men and Women and Other Civilian Activities, Including the Red Cross, the Y.M.C.A., the Y.W.C.A. and the War Camp Community Service, with Official Summary of Treaty of Peace and League of Nations Covenant. Chicago: Homewood Press, 1919. OCLC 1192364. (Reprinted: New York, Arno Press, 1969. OCLC 6100.)

- Williams, Charles H. Sidelights on Negro Soldiers. Boston: B.J. Brimmer Co, 1923. OCLC 1405294, 454411790. (Reprinted as: Negro Soldiers in World War I: The Human Side. New York: AMS Press, 1970. ISBN 0-404-06976-2).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 369th Infantry Regiment (United States). |

- 369th Regiment US Army color

- New York State Military Museum

- 719th Transportation Company, 369th Transportation Battalion in Iraq, 1990-91

- 369th Sustainment Brigade

- Headquarters, 369th Sustainment Brigade

- Early Element, 369th Sustainment Brigade

- 369th Signal Network Maintenance Company

- 145th Maintenance Company

- 133rd Quartermaster Company

- 719th Transportation Company

- 1569th Transportation Company

- 726th Military Police Detachment

- Arlington National Cemetery

- RedHotJazz.com article on the Hellfighter's Band

- The 369th - Harlem Hellfighters History

- The 371st Regiment Monument

- Journaux de Marche et des Opérations action reports of all World War I French units including 16th and 161st infantry divisions

- Jeffrey Sammons discusses the Harlem Hellfighters