Books of Kings

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The two Books of Kings (Hebrew: ספר מלכים Sepher M'lakhim – the two books were originally one)[1] present a history of ancient Israel and Judah from the death of David to the release of his successor Jehoiachin from imprisonment in Babylon, a period of some 400 years (c. 960 – c. 560 BCE).[2] It concludes a series of books running from Joshua through Judges and Samuel, which make up the section of the Hebrew Bible called the Former Prophets; this series is also often referred to as the Deuteronomistic history, a body of writing which scholars believe was written to provide a theological explanation for the destruction of the Jewish kingdom by Babylon in 586 BCE and a foundation for a return from exile.[2]

Contents

David dies and Solomon comes to the throne. At the beginning of his reign he assumes God's promises to David and brings splendour to Israel and peace and prosperity to his people.[3] The centrepiece of Solomon's reign is the building of the First Temple: the claim that this took place 480 years after the Exodus from Egypt marks it as a key event in Israel's history.[4] At the end, however, he follows other gods and oppresses Israel.[5]

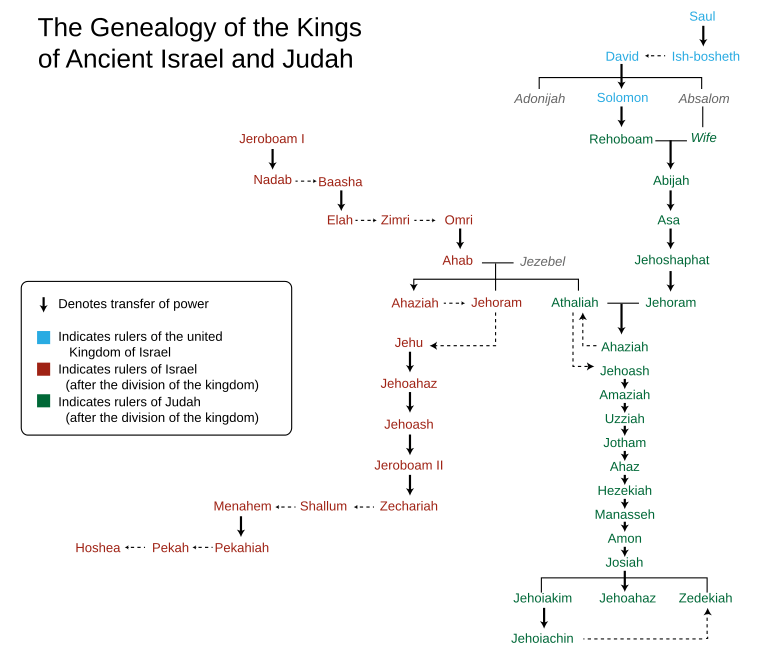

As a consequence of Solomon's failure to stamp out the worship of gods other than Yahweh, the kingdom of David is split in two in the reign of his own son Rehoboam, who becomes the first to reign over the kingdom of Judah.[6] The kings who follow Rehoboam in Jerusalem continue the royal line of David (i.e., they inherit the promise to David); in the north, however, dynasties follow each other in rapid succession, and the kings are uniformly bad (meaning that they fail to follow Yahweh alone). At length God brings the Assyrians to destroy the northern kingdom, leaving Judah as the sole custodian of the promise.

Hezekiah, the 14th king of Judah, "did what was right in the eyes of the Lord" and institutes a far reaching religious reform, centralising sacrifice at the temple at Jerusalem and destroying the images of other gods. Yahweh saves Jerusalem and the kingdom from an invasion by Assyria. But Manasseh, the next king, reverses the reforms, and God announces that he will destroy Jerusalem because of this apostasy by the king. Manasseh's righteous grandson Josiah reinstitutes the reforms of Hezekiah, but it is too late: God, speaking through the prophetess Huldah, affirms that Jerusalem is to be destroyed.

God brings the Babylonians against Jerusalem; Yahweh deserts his people, Jerusalem is razed and the Temple destroyed, and the priests, prophets and royal court are led into captivity. (The final verses record how Jehoiachin, the last king, is set free and given honour by the king of Babylon).

Composition

Textual history

In the original Hebrew Bible (the Bible used by Jews) First and Second Kings are a single book, as are First and Second Samuel. When this was translated into Greek in the last few centuries BCE, Kings was joined with Samuel in a four-part work called the Book of Kingdoms. The Greek Orthodox branch of Christianity continues to use the Greek translation (the Septuagint), but when a Latin translation (called the Vulgate) was made for the Western church, Kingdoms was first retitled the Book of Kings, parts One to Four, and eventually both Kings and Samuel were separated into two books each.[7]

Then, what it is now commonly known as 1 Samuel and 2 Samuel are called by the Vulgate, in imitation of the Septuagint, 1 Kings and 2 Kings respectively. What it is now commonly known as 1 Kings and 2 Kings would be 3 Kings and 4 Kings in old Bibles before the year 1516 such as the Vulgate and the Septuagint respectively.[8] The division we know today, used by Protestant Bibles and adopted by Catholics, came into use in 1517. Some Bibles still preserve the old denomination, for example, Douay Rheims bible.[9]

The Deuteronomistic history

According to Jewish tradition the author of Kings was Jeremiah, who would have been alive during the fall of Jerusalem in 586 BCE.[10] The most common view today accepts Martin Noth's thesis that Kings concludes a unified series of books which reflect the language and theology of the Book of Deuteronomy, and which biblical scholars therefore call the Deuteronomistic history.[11] Noth argued that the History was the work of a single individual living in the 6th century BCE, but scholars today tend to treat it as made up of at least two layers,[12] a first edition from the time of Josiah (late 7th century BCE), promoting Josiah's religious reforms and the need for repentance, and (2) a second and final edition from the mid 6th century BCE.[13] Further levels of editing have also been proposed, including: a late 8th century BCE edition pointing to Hezekiah of Judah as the model for kingship; an earlier 8th century BCE version with a similar message but identifying Jehu of Israel as the ideal king; and an even earlier version promoting the House of David as the key to national well-being.[14]

Sources

The editors/authors of the Deuteronomistic history cite a number of sources, including (for example) a "Book of the Acts of Solomon" and, frequently, the "Annals of the Kings of Judah" and a separate book, "Chronicles of the Kings of Israel". The "Deuteronomic" perspective (that of the book of Deuteronomy) is particularly evident in prayers and speeches spoken by key figures at major transition points: Solomon's speech at the dedication of the Temple is a key example.[13] The sources have been heavily edited to meet the Deuteronomistic agenda,[15] but in the broadest sense they appear to have been:

- For the rest of Solomon's reign the text names its source as "the book of the acts of Solomon", but other sources were employed, and much was added by the redactor.

- Israel and Judah: The two "chronicles" of Israel and Judah provided the chronological framework, but few details apart from the succession of monarchs and the account of how the Temple of Solomon was progressively stripped as true religion declined. A third source, or set of sources, were cycles of stories about various prophets (Elijah and Elisha, Isaiah, Ahijah and Micaiah), plus a few smaller miscellaneous traditions. The conclusion of the book (2 Kings 25:18–21, 27–30) was probably based on personal knowledge.

- A few sections were editorial additions not based on sources. These include various predictions of the downfall of the northern kingdom, the equivalent prediction of the downfall of Judah following the reign of Manasseh, the extension of Josiah's reforms in accordance with the laws of Deuteronomy, and the revision of the narrative from Jeremiah concerning Judah's last days.[16]

Themes and genre

According to Richard D. Nelson, Kings is "history-like," but it mixes legends, folktales, miracle stories and "fictional constructions" in with the annals, and its primary explanation for all that happens is God's offended sense of what is right; it is therefore more fruitful to read it as theological literature in the form of history.[17] The theological bias is seen in the way it judges each king of Israel on the basis of whether he recognises the authority of the Temple in Jerusalem (none do, and therefore all are "evil"), and each king of Judah on the basis of whether he destroys the "high places" (rivals to the Temple in Jerusalem); it gives only passing mention to important and successful kings like Omri and Jeroboam II and totally ignores one of the most significant events in ancient Israel's history, the battle of Qarqar.[18]

The major themes of Kings are God's promise, the recurrent apostasy of the kings, and the judgement this brings on Israel:[19]

- Promise: In return for Israel's promise to worship Yahweh alone, Yahweh makes promises to David and to Israel – to David, the promise that his line will rule Israel forever, to Israel, the promise of the land they will possess.

- Apostasy: the great tragedy of Israel's history, meaning the destruction of the kingdom and the Temple, is due to the failure of the people, but more especially the kings, to worship Yahweh alone (Yahweh being the god of Israel).

- Judgement: Apostasy leads to judgement. Judgement is not punishment, but simply the natural (or rather, God-ordained) consequence of Israel's failure to worship Yahweh alone.

Another and related theme is that of prophecy. The main point of the prophetic stories is that God's prophecies are always fulfilled, so that any not yet fulfilled will be so in the future. The implication, the release of Jehoiachin and his restoration to a place of honour in Babylon in the closing scenes of the book, is that the promise of an eternal Davidic dynasty is still in effect, and that the Davidic line will be restored.[20]

Textual features

Chronology

The standard Hebrew text of Kings presents an impossible chronology.[21] To take just a single example, Omri's accession to the throne of Israel in the 31st year of Asa of Judah (1 Kings 16:23) cannot follow the death of his predecessor Zimri in the 27th year of Asa (1 Kings 16:15).[22] The Greek text corrects the impossibilities but does not seem to represent an earlier version.[23] A large number of scholars have claimed to solve the difficulties, but the results differ, sometimes widely, and none has achieved consensus status.[24]

Kings and 2 Chronicles

2 Chronicles covers much the same time-period as Kings, but it ignores the northern Kingdom of Israel almost completely, David is given a major role in planning the Temple, Hezekiah is given a much more far-reaching program of reform, and Manasseh of Judah is given an opportunity to repent of his sins, apparently to account for his long reign.[25] It is usually assumed that the author of Chronicles used Kings as a source and re-wrote history as he would have liked it to have been.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Fretheim, p.1

- 1 2 Sweeney, p.1

- ↑ Fretheim, p.19

- ↑ Fretheim, p.40

- ↑ Fretheim, p.20

- ↑ Sweeney, p.161

- ↑ Tomes, p. 246

- ↑ [Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) Third and Fourth Books of Kings called in our days as First and Second of Kings https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_%281913%29/Third_and_Fourth_Books_of_Kings]

- ↑ [Douay Rheims bible http://www.drbo.org/]

- ↑ Spieckermann, p.337

- ↑ Perdue, xxvii

- ↑ Wilson, p.85

- 1 2 Fretheim, p.7

- ↑ Sweeney, p. 4

- ↑ Van Seters, p. 307

- ↑ McKenzie, pp. 281–284

- ↑ Nelson, pp.1–2

- ↑ Sutherland, p.489

- ↑ Fretheim, pp.10–14

- ↑ Sutherland, p.490

- ↑ Sweeney, p.43

- ↑ Sweeney, pp.43–44

- ↑ Nelson, p.44

- ↑ Moore & Kelle, pp.269–271

- 1 2 Sutherland, p.247

Bibliography

Commentaries on Kings

- Fretheim, Terence E (1997). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25565-7.

- Nelson, Richard Donald (1987). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

- Sweeney, Marvin (2007). I&II Kings: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

General

- Knight, Douglas A (1995). "Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomists". In James Luther Mays; David L. Petersen; Kent Harold Richards. Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-29289-6.

- Knight, Douglas A (1991). "Sources". In Watson E. Mills; Roger Aubrey Bullard. Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- Leuchter, Mark; Adam, Klaus-Peter (2010). "Introduction". In Mark Leuchter; Klaus-Peter Adam; Karl-Peter Adam. Soundings in Kings: Perspectives and Methods in Contemporary Scholarship. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-1263-5.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.

- McKenzie, Steven L (1994). "The Books of Kings". In Steven L. McKenzie; Matt Patrick Graham. The History of Israel's Traditions: The Heritage of Martin Noth. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-567-23035-5.

- Perdue, Leo G (2001). "Preface: The Hebrew Bible in Current Research". In Leo G. Perdue. The Blackwell companion to the Hebrew Bible. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21071-9.

- Spieckerman, Hermann (2001). "The Deuteronomistic History". In Leo G. Perdue. The Blackwell Companion to the Hebrew Bible. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21071-9.

- Sutherland, Ray (1991). "Kings, Books of, First and Second". In Watson E. Mills; Roger Aubrey Bullard. Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- Tomes, Roger (2003). "1 and 2 Kings". In James D. G. Dunn; John William Rogerson. Eerdmans commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

- Van Seters, John (1997). In search of history: historiography in the ancient world and the origins of biblical history. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-013-2.

- Walton, John H (2009). "The Deuteronomistic History". In Andrew E. Hill; John H. Walton. A Survey of the Old Testament. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-22903-2.

- Wilson, Robert R (1995). "The Former Prophets: Reading the Books of Kings". In James Luther Mays; David L. Petersen; Kent Harold Richards. Old Testament Interpretation: Past, Present and Future: Essays in honor of Gene M. Tucker. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-29289-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Books of Kings. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Hebrew Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Original text

- Kings A - Mikraot Gedolot Haketer - online edition, Menachem Cohen, Bar Ilan University (Hebrew)

- Kings B - Mikraot Gedolot Haketer - online edition, Menachem Cohen, Bar Ilan University (Hebrew)

- מלכים א Melachim Aleph – Kings A (Hebrew – English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

- מלכים ב Melachim Bet – Kings B (Hebrew – English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

Jewish translations

- 1 Kings at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society 1917 translation)

- 2 Kings at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society 1917 translation)

Christian translations

Other links

- "books of Kings." Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Books of Kings article (Jewish Encyclopedia)

- 1 & 2 Kings: introductionForward Movement

-

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "First and Second Books of Kings". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "First and Second Books of Kings". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. -

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Third and Fourth Books of Kings". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Third and Fourth Books of Kings". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

| Books of Kings | ||

| Preceded by Samuel |

Hebrew Bible | Succeeded by Isaiah |

| Christian Old Testament |

Succeeded by 1–2 Chronicles | |