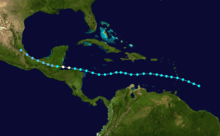

1960 Atlantic hurricane season

| |

| Season summary map | |

| First system formed | June 22, 1960 |

|---|---|

| Last system dissipated | September 26, 1960 |

| Strongest storm1 | Donna – 930 mbar (hPa) (27.46 inHg), 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| Total storms | 8 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 250 |

| Total damage | $910.7 million (1960 USD) |

| 1Strongest storm is determined by lowest pressure | |

1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962 | |

The 1960 Atlantic hurricane season was the least active season since 1952. The season officially began on June 15,[1] and lasted until November 15.[2] These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The first system, an unnamed storm, developed in the Bay of Campeche on June 22. It brought severe local flooding to southeastern Texas and was considered the worst disaster in some towns since a hurricane in 1945. The unnamed storm moved across the United States for almost a week before dissipating on June 29. In July, Hurricane Abby resulted in minor damage in the Leeward Islands, before impacting a few Central American counties — the remnants of the storm would go on to form Hurricane Celeste in the East Pacific. Later that month, Tropical Storm Brenda caused flooding across much of the East Coast of the United States. The next storm, Hurricane Cleo, caused no known impact, despite its close proximity to land.

The most significant storm of the season was Hurricane Donna, which at the time was among the ten costliest United States hurricanes. After the precursor caused a deadly plane crash in Senegal, the storm itself brought severe flooding and wind impacts to the Lesser Antilles and Florida, where Donna made landfall as a Category 4 hurricane. It moved northeast and struck North Carolina and Long Island, New York, while still at hurricane intensity. Donna caused at least 227 fatalities and $900 million (1960 USD) in damage. Hurricane Ethel reached Category 3 intensity, but rapidly weakened before making landfall in Mississippi, resulting in only 1 fatality and $1.5 million in losses. The final storm, Florence, developed on September 17. It remained weakened and moved erratically over Cuba and Florida. Only minor flooding was reported. Collectively, the tropical cyclones in 1960 caused at least 250 deaths and about $910.74 million in damage.

Season summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 15, 1960.[1] It was a below-average season in which seven tropical depressions formed. All seven of the depressions attained tropical storm status, which was below the 1950–2000 average of 9.6 named storms. Four of these reached hurricane status, also falling short of the 1950–2000 average of 5.9. Furthermore, two storms reached major hurricane status, which is Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Two hurricane and four tropical storms made landfall during the season and caused 387 deaths and $396.7 million (1960 USD) in damage.[3][4][5]

Season activity began on June 23, with the development of an unnamed tropical storm. Tropical cyclogenesis resumed in July with Hurricane Abby between July 10 and July 16, followed by Tropical Storm Brenda from July 28 to July 31. In mid-August, Hurricane Cleo developed and had an uneventful duration. At the end of that month, Hurricane Donna formed and lasted into mid-September; it was the strongest tropical cyclone of the season, peaking as a Category 4 hurricane. There was a Category 3 hurricane in September, Ethel, which briefly existed in the Gulf of Mexico. The last storm of the season, Tropical Storm Florence, dissipated on September 25, over a month before the official end of the season on November 15.[2][3]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 88, which was the lowest total since 54 in 1954.[6] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h) or tropical storm strength. Subtropical cyclones, such as the first storm, are excluded from the total.[7]

Storms

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | June 22 – June 28 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1000 mbar (hPa) | ||

Observations from a reconnaissance flight on June 22 indicated that a large area of showers and thunderstorms in the Gulf of Mexico was producing winds up to 40 mph (65 km/h). Because no circulation was reported, it was operationally classified as a tropical low, though radar stations along the Gulf Coast of Mexico indicated a circulation. Thus, the system became a tropical depression at 0600 UTC on June 22, while located in the Bay of Campeche. The depression strengthened and was estimated to have become a tropical storm on June 23. By early on the following day, the storm peaked with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). Later that day, it made landfall near Corpus Christi, Texas at the same intensity. The storm weakened slowly and moved across the Central United States, before dissipating over Illinois on June 29.[3]

In Texas, the storm dropped up to 29.76 inches (756 mm) of precipitation in Port Lavaca.[8] Thus considerable flooding occurred in some areas of south and eastern Texas. Throughout the state, more than 150 houses sustained flood damage in several counties. In addition, numerous major highways were closed, including portions of U.S. Routes 59, 87, 90, and 185, and Texas State Highways 35 and 71.[9][10] In Arkansas, a few buildings in Hot Springs were damaged from high winds. Elsewhere, light to moderate rainfall was recorded in at least 11 other states, though damage was minimal.[8] The storm was the rainiest tropical cyclone on record in the state of Kentucky, dropping 11.25 inches (286 mm) in Dunmor.[11] Overall, the storm was attributed to 15 fatalities and $3.6 million in damage.[3]

Hurricane Abby

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 9 – July 17 | ||

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression near the Windward Islands on July 10. While crossing the islands later that day, the depression rapidly strengthened into Hurricane Abby. It tracked westward across the Caribbean Sea and peaked as a 100 mph (155 km/h) Category 2 hurricane on July 11. Thereafter, Abby became disorganized and weakened back to a tropical storm on July 13. The storm began to re-organize starting on the following day, and re-acquired hurricane status while located offshore Honduras. The storm made landfall in British Honduras (present day Belize) as a minimal hurricane on July 15. Abby quickly weakened inland and by the next day, it dissipated over the Mexican state of Tabasco. However, the remnants later contributed to the development of Hurricane Celeste in the eastern Pacific.[3]

Abby produced tropical storm force winds and up to 6.8 inches (170 mm) of precipitation in St. Lucia. Six people died when a roof of a house collapsed. Damage in St. Lucia reached $435,000, most of which was incurred to banana and coconut crops. In Martinique, wind gusts of 75 mph (120 km/h) and about 4 inches (100 mm) of rain damaged 33% of banana and sugar cane crops. The resultant landslides from the precipitation extensively impacted roads and bridges.[3] In Dominica, light winds and precipitation up to 5.91 inches (150 mm) reaching $65,000, entirely to roads and communications.[12] Offshore islands of Honduras reported winds up to 52 mph (85 km/h) and light rainfall.[13] Damage in British Honduras was light, with about $40,500 in losses, mostly to agriculture.[14]

Tropical Storm Brenda

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 27 – July 31 | ||

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 991 mbar (hPa) | ||

A weak low-pressure area into the Gulf of Mexico developed into a tropical depression on July 28. It failed to intensify significantly before making landfall near Cross City, Florida.[3] The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Brenda at around 1200 UTC on July 29 while its center was situated over southeast Georgia.[15] Brenda tracked northward along the Georgia and South Carolina coasts, before moving inland over North Carolina. It attained its peak winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) at 0000 UTC on July 30.[15] Several hours later, the storm emerged over the Chesapeake Bay,[16] before crossing the Delmarva Peninsula and accelerating into southern New Jersey. The storm passed over the state and eventually crossed Long Island before making another landfall in Connecticut.[15] Early on July 31, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[15]

Brenda was considered the worst storm to strike West Central Florida since Hurricane Easy in 1950.[17] It brought wind gusts up to 60 mph (95 km/h) and rainfall amounts reaching 14.57 inches (370 mm) at the Tampa International Airport. While no casualties are directly blamed on the storm, at least one traffic-related death took place.[3] According to an American Red Cross Disaster Service report encompassing eight Florida counties, 11 houses sustained significant damage, while 567 suffered more minor damage. Around 590 families were affected overall. Total monetary damage in Florida is placed at nearly $5 million.[17] Further north, other states reported strong winds and locally heavy rainfall,[18] though no significant damage occurred.[3]

Hurricane Cleo

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 17 – August 21 | ||

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) | ||

A strong tropical wave produced rainfall and gusty winds in The Bahamas and the Greater Antilles in mid-August. The wave was closely monitored for possible tropical cyclogenesis and special bulletins were issued by the United States Weather Bureau.[19] At 1800 UTC on August 17, Tropical Storm Cleo developed near Cat Island in The Bahamas. The storm headed northeastward and immediately began to intensify.[15] Operationally, the United States Weather Bureau at the hurricane warning center in Miami did not initiate advisories on Cleo until 1500 UTC on August 18. Sustained winds were already 70 mph (110 km/h) at the time, as recorded by a reconnaissance aircraft flight.[20] By 1800 UTC on August 18, Cleo strengthened into a hurricane.[15]

Throughout its duration, Cleo remained a relatively small tropical cyclone. Because the storm posed a significant threat to New England, a "hurricane watch" was issued for southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island on August 19. Various gale warnings were also put into effect from Block Island, Rhode Island, to Portland, Maine. However, this was unnecessary because Cleo remained well offshore.[20] Early on August 20, Cleo peaked with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h). Thereafter, the storm began to weaken and fell to tropical storm intensity while south of Nova Scotia later that day. Cleo curved east-northeastward on August 20. The storm passed near Sable Island early on August 21, before dissipating later that day.[15]

Hurricane Donna

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 29 – September 13 | ||

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) 930 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave, which was attributed to 63 deaths from a plane crash in Senegal,[21] developed into a tropical depression centered south of Cape Verde late on August 29. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Donna by the following day. Donna moved west-northwestward at roughly 20 mph (32 km/h) and by September 1, it reached hurricane status. Significant deepening occurred during the next 30 hours, with Donna being a moderate Category 4 hurricane by late on September 2. Thereafter, it weakened some and brushed the Lesser Antilles later that day.[15] On Sint Maarten, the storm left a quarter of the island homeless and killed 7 people. An additional 5 deaths were reported in Anguilla and there were 7 other deaths throughout the Virgin Islands. In Puerto Rico, severe flash flooding led to 107 fatalities, 85 of them in Humacao alone.[3] Donna further weakened to a Category 3 hurricane late on September 5, but eventually became a Category 4 hurricane again.[15] While passing through The Bahamas, several small island communities in the central regions of the country were leveled, but no damage total or fatalities were reported.[3]

Early on September 10, Donna made landfall near Marathon, Florida on Vaca Key with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h), hours before another landfall between Fort Myers and Naples at the same intensity.[15] Florida bore the brunt of Hurricane Donna. In the Florida Keys, coastal flooding severely damaged 75% of buildings, destroyed several subdivisions in Marathon. On the mainland, 5,200 houses were impacted, which does not include the 75% of homes damaged at Fort Myers Beach; 50% of buildings were also destroyed in the city of Everglades.[22] Crop losses were also extensive. A total of 50% of grapefruit crop was lost, 10% of the orange and tangerine crop was lost, and the avocado crop was almost completely destroyed.[23] In the state of Florida alone, there were 13 deaths and $300 million in losses.[3] Donna weakened over Florida and was a Category 2 hurricane when it re-emerged into the Atlantic from North Florida. By early on September 12, the storm made landfall near Topsail Beach, North Carolina with winds of 110 mph (175 km/h).[15] Donna brought tornadoes and wind gusts as high as 100 mph (155 km/h), damaging or destroying several buildings in Eastern North Carolina, while crops were impacted as far as 50 miles (80 km) inland. Additionally, storm surge caused significant beach erosion and structural damage Wilmington and Nags Head. There were 8 deaths and over 100 injuries.[24] Later on September 12, Donna reemerged into the Atlantic Ocean and continued to move northeastward. The storm struck Long Island, New York late on September 12 and rapidly weakened inland. On the following day, Donna became extratropical over Maine.[15]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 1 – September 3 | ||

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1009 mbar (hPa) | ||

Hurricane Ethel

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 12 – September 17 | ||

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 974 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical disturbance in the central Gulf of Mexico developed into Tropical Storm Ethel on September 14. Ethel rapidly intensified, becoming a hurricane six hours later and a major hurricane by early on September 15. The storm peaked as a Category 3 hurricane later that day, despite an abnormally high minimum pressure of 974 mbar (28.8 inHg). Cool and dry air began impacting Ethel, causing it to rapidly weaken back to a Category 1 hurricane while brushing eastern Louisiana. Later on September 15, Ethel was downgraded to a tropical storm. Early on the following day, Ethel made landfall in Pascagoula, Mississippi with sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). The storm gradually weakened after moving inland, before eventually dissipating over southern Kentucky on September 17.[15]

In Louisiana, the outerbands of the storm produced light rainfall and hurricane-force winds, though no damage was reported in that state.[25] Offshore Mississippi, rough seas inundated Horn Island and split Ship Island.[26] Tropical storm force winds in the southern portion of the state littered broken glass, trees, and signs across streets in Pascagoula, as well as down power lines, which caused some residents to lose power.[27] In Alabama, winds damaged beach cottages along the Gulf Coast, and damaged crops in the southern portion of the state.[24] Although large amounts of rain fell in the extreme western portions of Florida, peaking at 12.94 inches (329 mm) in Milton, no flooding occurred in Florida.[28] A lightning strike to a power station near Tallahassee caused a brief city-wide blackout.[29] The storm spawned four tornadoes in Florida,[24] one of which destroyed 25 homes.[30] Outside the Gulf Coast of the United States, rain fell in 8 others states, but no damage is known to have occurred.[28] Overall, Ethel caused 1 fatality and $1.5 million in losses.[3][24][31]

Tropical Storm Florence

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 17 – September 26 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1000 mbar (hPa) | ||

A westward moving tropical wave developed into a tropical depression while located north of Puerto Rico on September 17. By the following day, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Florence. Later on September 18, Florence peaked as a 45 mph (75 km/h) tropical storm as it approached The Bahamas. However, unfavorable conditions weakened the storm back to a tropical depression on September 19. Little change in intensity occurred before Florence made landfall in western Cuba on September 21. The storm executed a small cyclonic loop over Cuba before eventually emerging into the Straits of Florida. Florence then tracked northeastward and made landfall in Monroe County, Florida on September 23. The storm drifted across the state slowly and reemerged into the Gulf of Mexico after more than 24 hours over Florida.[3]

By September 26, Florence made landfall near the Alabama-Florida border and dissipated over Mississippi on the following day.[3] On Grand Bahama, 5.48 inches (139 mm) of rain fell in only 6 hours.[32] No impact was reported in Cuba.[3] The storm dropped rainfall across Florida, though the heavier amounts were mainly on the Atlantic coast. Precipitation peaked at 15.79 inches (401 mm) near Fellsmere, while rainfall reached 10 inches (250 mm) in some areas of the Miami metropolitan area.[33] Although Florence was a depression at landfall,[3] sustained winds between 35 and 40 mph (56 and 64 km/h) were recorded in Ocean Ridge,[34] while a gust as high as 52 mph (84 km/h) was reported in Vero Beach.[3] In Jacksonville, a pressure gradient combined with Florida to produce tides of 2 to 3 feet (0.61 to 0.91 m) about normal.[32]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1960. Storms were named Abby and Donna for the first time in 1960.[35] Following the season, the name Donna was retired, replaced with Dora.[36] Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

|

|

See also

- 1960 Pacific hurricane season

- 1960 Pacific typhoon season

- 1960 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- Lists of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

References

- 1 2 "1960 Hurricane Season Open As Planes Prowl". The Evening Independent. Jacksonville, Florida. Associated Press. June 15, 1960. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Hunters Go Away Till The Next Time". The Miami News. November 15, 1960. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Gordon E. Dunn (March 1961). The Hurricane Season of 1960 (PDF). United States Weather Bureau; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ↑ Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Jack L. Beven (April 22, 1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ Arnold L. Sugg (March 1966). The Hurricane Season Of 1965 (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- 1 2 David M. Roth (March 12, 2007). Unnamed Tropical Storm – June 22–29, 1960 (Report). College Park, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ AOE Report – Closed Highways (GIF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 26, 1960. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ↑ Information For Highway Patrol (GIF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 26, 1960. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ↑ Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (January 7, 2013). "Maximum Rainfall caused by Tropical Cyclones and their Remnants Per State (1950–2012)". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ↑ Hurricane Abby Preliminary Report. United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. 1960. p. 2. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Abby Breaking Up In Honduras". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. July 15, 1960. p. 4. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ Richard D. Geppert (August 3, 1960). Hurricane Abby. United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Carlson (July 30, 1960). Local Statement on Tropical Storm Brenda (GIF). United States Weather Bureau Office Hillsgrove, Rhode Island (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- 1 2 Keith Butson (August 11, 1960). Report on incipient tropical storm Brenda, July 28–29, 1960 (GIF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ↑ Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ↑ Preliminary Report on Hurricane Cleo, August 18–20, 1960. United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 1. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- 1 2 Davis (August 18, 1960). Miami Weather Bureau Bulletin. United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami: National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 3. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ Late Twentieth Century. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Report). College Park, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. March 1, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ 1. Category A – Flood Report NR 2.2 A. Telephone Reports. United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1960. p. 1. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ↑ Hurricane Donna – September 3–13, 1960. United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 27, 1960. p. 2. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena: September 1960 (PDF). National Climatic Data Center (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1960. pp. 111–115. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ Hurricane Ethel Preliminary Report (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. December 27, 1960. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ↑ Robert A. Morton (2007). Historical Changes in the Mississippi-Alabama Barrier Islands and the Roles of Extreme Storms, Sea Level, and Human Activities (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Hurricane Ethel rips coast of Mississippi". The Bulletin. United Press International. September 15, 1960. p. 1.

- 1 2 David M. Roth (October 5, 2009). Hurricane Ethel – September 14–17, 1960. Weather Prediction Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Ethel". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. September 16, 1960. p. 2. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Ethel Hits 3 Coastal Cities, Then Fades Out Over Land". St. Petersburg Times. Mobile, Alabama. Associated Press. September 16, 1960. p. 1. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Cleanup slowed in wake of Hurricane Ethel". The Bulletin. Pascagoula, Mississippi. United Press International. September 16, 1960. p. 6. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- 1 2 Gilbert B. Clark (September 24, 1960). "Miami Weather Bureau Bulletin" (GIF). United States Weather Bureau Office Miami, Florida. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ↑ David M. Roth (December 20, 2009). Tropical Storm Florence – September 19–27, 1960. Weather Prediction Center (Report). College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ↑ Gilbert P. Clark (September 23, 1960). Miami Weather Bureau Bulletin (GIF). United States Weather Bureau Office Miami, Florida (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Name a Hurricane After Me, Woman Asks Weather Bureau". The Milwaukee Journal. Washington, D.C. July 23, 1960. p. 12. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 11, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

.jpg)