1901 Federal Flag Design Competition

The 1901 Federal Flag Design Competition was an Australian government initiative announced by Prime Minister Edmund Barton to find a flag for the newly federated Commonwealth of Australia.[1] In terms of its essential elements the winning entry is the official flag of Australia.

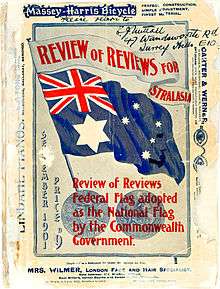

After Federation on 1 January 1901 and following receipt of a request from the British government to design a new flag, the new Commonwealth Government held an official competition for a new federal flag in April. The competition attracted 32,823 entries,[2] including those originally sent to the one held earlier by the Review of Reviews.[2] One of these was submitted by an unnamed governor of a colony.[3] The two contests were merged after the Review of Reviews agreed to being integrated into the government initiative. The £75 prize money of each competition were combined and augmented by a further £50 donated by Havelock Tobacco Company.[2] Each competitor was required to submit two coloured sketches, a red ensign for the merchant service and public use, and a blue ensign for naval and official use. The designs were judged on seven criteria: loyalty to the Empire, Federation, history, heraldry, distinctiveness, utility and cost of manufacture.[4] The majority of designs incorporated the Union Flag and the Southern Cross, but native animals were also popular, including one that depicted a variety of indigenous animals playing cricket.[3] The entries were put on display at the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne and the judges took six days to deliberate before reaching their conclusion.[3] Five almost identical entries were chosen as the winning design, and their designers shared the £200 (2015: $29,142.12) prize money. They were Ivor Evans, a fourteen-year-old schoolboy from Melbourne; Leslie John Hawkins, a teenager apprenticed to an optician from Sydney; Egbert John Nuttall, an architect from Melbourne; Annie Dorrington, an artist from Perth; and William Stevens, a ship's officer from Auckland, New Zealand. The five winners received £40 each.[3] The differences from the present flag were the six-pointed Commonwealth Star, while the components stars in the Southern Cross had different numbers of points, with more if the real star was brighter. This led to five stars of nine, eight, seven, six and five points respectively.[3]

A simplified version of the competition-winning design was submitted to the British Parliament in December 1901. Prime Minister Edmund Barton announced in the Commonwealth Gazette that Edward VII had officially recognised the design as the Flag of Australia on 11 February 1903.[5] This version made all the stars in the Southern Cross seven-pointed apart from the smallest, and is the same as the existing flag except the six-pointed Commonwealth Star.[6]

Misconceptions

In February 11 1903 There were five judges for the competition and not seven. This seems to have arisen from the Review of Reviews listing the seven names of the competition's "judges and officials" (20 September 1901, p. 241). The Review of Reviews gives the names of the five judges on p. 128 of its 20 August 1901 edition, and confirms their number on p. 241 of its 20 September 1901 edition. Mr J.S. Blackham, chief of staff of the Melbourne Herald, was the competition official "who superintended the classification and arrangement of the flags" for "when they were shown in Melbourne's Exhibition Building" (see The Review of Reviews, 20 August 1901, p. 127; 20 September 1901, pp. 241, 243, 244). Mr G. Stewart was another competition official (see The Review of Reviews, 20 September 1901, pp. 243); Frank Cayley has described Stewart as "an expert in heraldry".[7][8][9][10]

Several secondary sources have claimed that it was a condition that each entry had to have a Union Jack. In fact, neither the Government's competition rules, nor the Review of Reviews' competition rules, specifically asked for a Union Jack as a condition of entry (although any entry without one would be expected to have little chance of success).

However, it has been repeatedly stated that the competition rules stipulated that the design should "be based on the British ensigns ... signalling to the beholder that it is an Imperial union ensign of the British Empire". There was no such competition rule. This error stems from Gwen Swinburne's 1969 book, Unfurled: Australia's Flag, in which she incorrectly attributes the above quote as a condition for the 1901 flag competition. She had apparently used a passage from Barlow Cumberland's 1909 book, History of the Union Jack and the Flag of the Empire, as the basis of her quote.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

References

- ↑ Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. 27

- 1 2 3 Australian Flags, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Australian Flags, p. 40.

- ↑ Evans, I. 1918. The history of the Australian flag. Evan Evans, Melbourne

- ↑ Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. 8, 20 February 1903

- ↑ Australian Flags, p. 41.

- ↑ Cayley, op. cit., p. 98.

- ↑ Ivor Evans, "History of the Australian Flag", in Crux Australis: Journal of the Flag Society of Australia, Vol. 1/1 (June 2, 1984), p. 37.

- ↑ The Review of Reviews for Australasia, 20 August 1901, p. 127, 128; 20 September 1901, p. 241, 243, 244.

- ↑ John C. Vaughan, "Australia's National Flag Competition", in Crux Australis: Journal of the Flag Society of Australia, Vol. 2/1, No. 7 (July 1985), p. 21-22.

- ↑ Barlow Cumberland, History of the Union Jack and the Flag of the Empire, William Briggs, Toronto, 1909, p. 289.

- ↑ Crux Australis: Journal of the Flag Society of Australia, Vol. 8/3, No. 35 (July–September 1992), p. 141 (endnote 10).

- ↑ G.H. Swinburne, Unfurled: Australia's Flag, Sirius Publications, Melbourne, 1969, p. 76.

- ↑ June Cadzow, "Standard Debate Over the Ensign Raised Up Again", in The Australian, 26 January 1984.

- ↑ Our Own Flag, (Ausflag pamphlet).

- ↑ Henry Reynolds, "An Erstwhile Ensign", in Modern Times, June 1992, pp. 4-5.