Æthelberht II of East Anglia

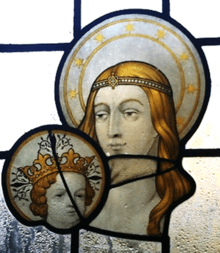

Æthelberht (Old English: Æðelbrihte), also called Saint Ethelbert the King, (died 20 May 794 at Sutton Walls, Herefordshire) was an eighth-century saint and a king of East Anglia, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom which today includes the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. Little is known of his reign, which may have begun in 779, according to later sources, and very few of the coins issued during his reign have been discovered. It is known from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that he was killed on the orders of Offa of Mercia in 794.

He was subsequently canonised and became the focus of cults in East Anglia and at Hereford, where the shrine of the saintly king once existed. In the absence of historical facts, mediaeval chroniclers provided their own details for Æthelberht's ancestry, life as king and death at the hands of Offa. His feast day is 20 May. Several Norfolk, Suffolk and West Country parish churches are dedicated to the saint.

Life and reign

Little is known of Æthelberht's life or reign, as very few East Anglian records have survived from this period. Mediaeval chroniclers have provided dubious accounts of his life, in the absence of any real details. According to Richard of Cirencester, writing in the fifteenth century, Æthelberht's parents were Æthelred I of East Anglia and Leofrana of Mercia. Richard narrates in detail a story of Æthelberht's piety, election as king and wise rule. Urged to marry against his will, he apparently agreed to wed Eadburh, the daughter of Offa of Mercia, and set out to visit her, despite his mother's forebodings and his experiences of terrifying events (an earthquake, a solar eclipse and a vision).[1]

Æthelberht's reign may have begun in 779, the date provided for the beginning of his reign on the uncertain authority of a much later saint's life. The absence of any East Anglian charters prevents it from being known whether he ruled as a king or a sub-king under the power of the ruler of another kingdom.

Æthelberht was stopped by Offa of Mercia from minting his own coins,[2] of which only four [3] examples have ever been found. One of these coins, a 'light' penny, said to have been found in 1908 at Tivoli, near Rome, is similar in type to the coinage of Offa. On one side is the word REX, with an image of Romulus and Remus suckling a wolf: the obverse names both the king and his moneyer, Lul, who struck coins for both Offa and Coenwulf of Mercia. Andy Hutcheson has suggested that the use of runes on the coin may signify "continuing strong control by local leaders".[4] According to Marion Archibald, the issuing of "flattering" coins of this type, with the intention to win friends in Rome, probably indicated to Offa that as a sub-king, Æthelberht was assuming "a greater degree of independence than he was prepared to tolerate".[5]

In 793 the vulnerability of the English east coast was exposed when the monastery at Lindisfarne was looted by Vikings and a year later Jarrow was also attacked, events which Steven Plunkett reasons would ensure that the East Anglians were governed firmly. Æthelberht's claim to be a king descended from the Wuffingas dynasty (suggested by the use of a Roman she-wolf and the title REX on his coins) could be because of a need for strong kingship as a result of the Viking attacks.[6]

Death and canonisation

| Æthelberht II of East Anglia | |

|---|---|

| Venerated in |

Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Communion, Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | previously at Hereford Cathedral |

| Feast |

20 May, 29 May in Eastern Orthodox Church |

Æthelberht was put to death by Offa of Mercia under unclear circumstances; the site of his murder was apparently the royal vill at Sutton Walls.[7] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, he was beheaded.[8][9] Mediaeval sources tell how he was taken captive whilst visiting his future Mercian bride Ælfthyth and was then murdered and buried. In Richard of Cirencester's account of the murder, which cannot be substantiated, Offa's evil queen Cynethryth poisoned her husband's mind until he agreed to have his guest killed. Æthelberht was then bound and beheaded by a certain Grimbert and his body was unceremoniously disposed of. The mediaeval historian John Brompton's Chronicon describes how the king's detached head fell off a cart into a ditch where it was found, before it restored a blind man's sight. According to the Chronicon, Ælfthyth subsequently became a recluse at Crowland and her remorseful father founded monasteries, gave land to the Church and travelled on a pilgrimage to Rome.[1]

The execution of an Anglo-Saxon king on the orders of another ruler was very rare, although public hanging and beheading did occur at this time, as has been discovered at the Sutton Hoo site.[10] Æthelberht's death at the hands of the Mercians made the possibility of any peaceful union between the Anglian peoples (including Mercia) less likely than before.[11] It led to Mercia's domination of East Anglia, whose kings ruled over the kingdom for over three decades after Æthelberht's death.

In 2014 metal-detectorist Darrin Simpson of Eastbourne found a coin minted during the reign of Æthelbert, in a Sussex field. It is believed that the coin may have led to Æthelbert's beheading by Offa, as it had been struck as a sign of independence.[12] Describing the coin, Christopher Webb, head of coins at auctioneers Dix Noonan Webb, said, "This new discovery is an important and unexpected addition to the numismatic history of 8th Century England." It sold at auction on June 11 for £78,000 (estimate £15,000 to £20,000).[13]

Legacy

Veneration

After his death, Æthelberht was canonised by the Church. He became the subject of a series of vitae that date from the eleventh century and he was venerated in religious cults in both East Anglia and at Hereford. The Anglo-Saxon church of the episcopal estate at Hoxne was one of several dedicated to Æthelberht in Suffolk,[14] a possible indication of the existence of a religious cult devoted to the saintly king.[15] Only three dedications for Æthelberht are near where he died - Marden, Hereford Cathedral and Littledean - the other eleven being in Norfolk or Suffolk. Lawrence Butler has argued that this unusual pattern may be explained by the existence of a royal cult in East Anglia, which represented a "revival of Christianity after the Danish settlement by commemorating a politically 'safe' and corporeally distant local ruler".[16]

Christian buildings dedicated to Æthelberht

The Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Ethelbert are joint patrons the cathedral at Hereford, where the music for the Office of St Ethelbert survives in the thirteenth-century Hereford Breviary.

In East Anglia, St. Ethelbert's Gate is one of the two main entrances to the precinct of Norwich Cathedral. The chapel at Albrightestone, at a location near an important excavated Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Boss Hall in Ipswich, was dedicated to Æthelberht. In Norfolk, the Church of England parish churches at Alby, East Wretham, Larling, Thurton, Mundham and Burnham Sutton (where there are remains of the ruined church) and the Suffolk churches at Falkenham, Hessett, Herringswell and Tannington are all dedicated to the saint. In neighbouring Essex, the parish church at Belchamp Otten is dedicated to St Ethelbert and All Saints, and the church at Stanway, originally an Anglo-Saxon chapel, is dedicated to St Albright, which is believed to be the same saint.[17] In 1937, St Ethelbert's name was added to the parish church of St George in East Ham, London, at the behest of Hereford Cathedral which had funded the rebuilding of the church, previously a temporary wooden structure.[18]

References

- 1 2 Internet Archive - The Catholic Encyclopedia (Ethelbert)

- ↑ Kirby 2000, p. 147.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-suffolk-27795641

- ↑ Hutcheson, The Origin of East Anglian Towns, p. 203.

- ↑ Archibald, Coinage of Beonna, p. 34.

- ↑ Plunkett 2005, pp. 171–72.

- ↑ Yorke 2002, p. 9.

- ↑ Swanton, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, p. 55.

- ↑ Her Offa Myrcena cining het Æðelbrihte þet heafod ofslean, (from an online version of the Chronicle.)

- ↑ Plunkett 2005, p. 173.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, p. 148.

- ↑ "BBC News - 'Unique' Anglo-Saxon coin could give royal murder clue". Bbc.co.uk. 2014-05-20. Retrieved 2014-06-14.

- ↑ "Anglo-Saxon coin goes for £78,000 at London auction". Eastbourne Herald. Retrieved 2014-06-14.

- ↑ The church is mentioned in the will of Theodreusus, Bishop of London and Hoxne (c. 938 – c. 951)

- ↑ Warner 1996, p. 123.

- ↑ Butler, Lawrence (1986). "Church dedications and the cults of Anglo-Saxon saints in England" (PDF). In Butler, L. A. S.; Morris, R. K. The Anglo-Saxon Church (PDF). London: Council for British Archaeology Research Report. pp. 44–50. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ↑ Buckler, George (1856) Twenty-Two Of The Churches Of Essex: Architecturally Described And Illustrated, Bell and Daldy, London (p. 242)

- ↑ "St. George and St. Ethelbert's website - About us". Parish Church of St. George and St. Ethelbert. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

Sources

- Archibald, Marion M. (1985). "The Coinage of Beonna in the light of the Middle Harling Hoard" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 55: 10–54.

- Baring-Gould, S. (1877). The Lives of the Saints. Internet Archive: London (John C. Nimmo).

- Hutcheson, Andrew (2009). "Coinage in the East Anglian Landscape c. AD 749–939: from Beonna through to the Death of Athelstan". The Origins of East Anglian Towns: Coin Loss in the Landscape, AD 470-939 (PDF) (Ph.D.). University of East Anglia.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-4152-4211-8.

- Plunkett, S. J. (2005). Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3139-0.

- Swanton, Michael (1997). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- Warner, Peter (1996). The origins of Suffolk. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3817-0.

- Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon English. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Æthelberht II of East Anglia. |

- Æthelberht 11 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- A mid-Victorian account of Æthelberht's death from Lives of the Queens of England Before the Norman Conquest (1854), by Mrs. Matthew Hall.

- 'The Murder of King Ethelbert of East Anglia - 794 AD', (produced by Hereford Web Pages)

- 'St Ethelbert's Holy Well', (produced by Mysterious Britain and Ireland)

- Times Online article about the modern shrine to St. Ethelbert in Hereford Cathedral, and a link to an image of the shrine.

| Preceded by Æthelred I |

King of East Anglia | Succeeded by Offa of Mercia |